The economic expansion that followed the Great Recession was the longest in post-war history. But many people, especially those with low-to-moderate incomes, were already on an economic knife edge before the COVID-19 pandemic struck.

The jobs numbers certainly looked rosy: from 2008 to 2019, Washington added nearly 479,000 nonfarm jobs. Over the same time frame, average hourly wages climbed 22.6 percent after adjusting for inflation.[1] But most of those wage gains accrued to a relatively small group of people working in a select few economic sectors. For everyone else, wage growth was sluggish – at best – making it next-to-impossible to build economic security in the event of a downturn.

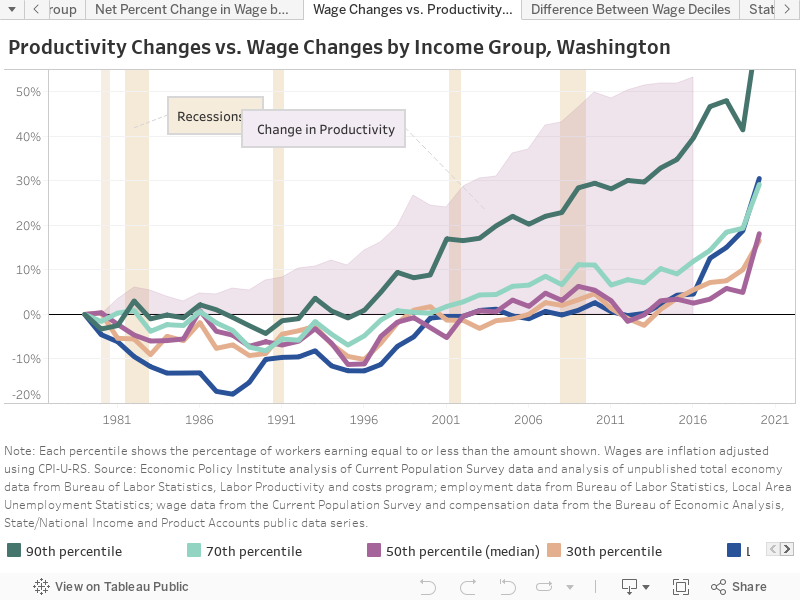

This isn’t a new trend: most Washington workers haven’t made real economic gains in decades. From 1979 to 2019, hourly wages for the bottom 50 percent of workers have increased $1.00/hour or less (about 5 percent), despite the fact that overall economic productivity climbed 53 percent (through 2016).[2] Nearly all of the economic gains of the past 40 years have gone to the top 30 percent of workers.

In most of Washington’s biggest employment sectors, wage gains since the Great Recession were meager.[3] In the state’s nine largest sectors – which comprise 73 percent of all nonfarm employment and have contributed nearly 7 in 10 new jobs from 2008 to 2019 – average wages increased just $978, or 1.9 percent, annually. But that actually overstates the wage gains made by most workers.

Above-average wages in Nonstore retail (think Amazon) account for just 1.5 percent of the state’s total jobs in 2018, but 25 percent of that overall wage increase. Excluding Nonstore retail, average wages increased just $726 (1.4 percent) annually from 2008 to 2019. Meanwhile, in the state’s manufacturing sector, outside of aerospace (where wages are above average but employment growth is basically flat), wages were below average, and there were 3450 fewer jobs than at the start of the Great Recession.

Job and Wage Growth: High Employment Sectors

| Sector | Total Jobs 2019 Q4 (% of total) | New Jobs 2008 Q1-2019 Q4 (% of total) | Avg. Wage 2019 Q2 (vs. WA avg.) | Avg. Annual Wage Increase 2008 Q1-2019 Q2 (%) |

| Health Care and Social Assistance | 439,217 (12.6%) |

92,525 (19.3%) |

$53,823 (-$29,234) |

$413 (0.8%) |

| Retail Trade | 389,958 (11.2%) |

62,592 (13.1%) |

$62,064 (-$20,993) |

$2,475 (7.1%) |

| Retail Trade (less Nonstore retailers)* |

337,128 (9.7%) |

21,635 (4.5%) |

$40,305 (-$42,753) |

$680 (2.1%) |

| Nonstore retailers* | 52,831 (1.5%) |

40,957 (8.6%) |

$206,195 (+$123,138) |

$10,718 (12.1%) |

| Local Government | 361,833 (10.4%) |

38,200 (8.0%) |

$61,529 (-$21,529) |

$709 (1.3%) |

| Accommodation and Food Services | 293,442 (8.5%) |

57,500 (12.0%) |

$24,469 (-$58,589) |

$447 (2.3%) |

| Manufacturing | 293,408 (8.4%) |

1942 (-0.8%) |

$85,212 (+$2,155) |

$1,112 (1.5%) |

| Manufacturing (less aerospace) |

205,025 (5.9%) |

-3,450 (-0.7%) |

$65,585 (-$17,473) |

$457 (0.8%) |

| Aerospace | 88,383 (2.5%) |

5392 (1.1%) |

$132,416 (+$49,359) |

$2,578 (2.5%) |

| Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services | 218,408 (6.3%) |

51,508 (10.8%) |

$101,354 (+$18,296) |

$1,625 (1.9%) |

| Construction | 219,725 (6.3%) |

19,267 (4.0%) |

$65,516 (-$17,542) |

$600 (1.0%) |

| Administrative and Support Services | 158,475 (4.6%) |

25,708 (5.4%) |

$50,887 (-$32,170) |

$919 (2.3%) |

| State Government | 149,750 (4.4%) |

-2,942 -(0.6%) |

$67,197 (-$15,861) |

$708 (1.2%) |

| Total/Average | 2,524,217 (73%) |

346,300 (72%) |

$62,176 (-$20,881) |

$978 (1.9%) |

Sources: 1) Employment Estimates (WA-QB, not seasonally adjusted) through December 2019 (preliminary), and 2) Covered Employment (QCEW) through June 2019 (preliminary), shown as annualized four-quarter rolling averages, with wages expressed in 2019 dollars using CPI-U-RS (estimated). *2018-19 Retail Trade (less Nonstore retailers) and Nonstore retailers wage data is estimated based on overall sector trends.

Meanwhile, a handful of high-wage job categories have been reaping most of the gains of a growing economy.[4] Four sectors (Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services; Information; Finance and Insurance; and Management of Companies and Enterprises) — which together comprise just 15 percent of nonfarm employment — have seen annual wage increases averaging $3,634 (3.8 percent) since 2008. Wage increases in Software Publishing, which accounts for just under half of all Information sector jobs, are particularly outsized, averaging $9,133 (5.3 percent) per year.

Job and Wage Growth: High Wage Sectors

| Sector | Total Jobs 2019 Q4 (% of total) |

New Jobs 2008 Q1-2019 Q4 (% of total) | Avg. Wage 2018 Q2 (vs. WA avg.) | Avg. Annual Wage Increase 2008 Q1-2019 Q2 (%) |

| Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services | 218,408 (6.3%) |

51,508 (10.8%) |

$101,354 (+$18,296) |

$1,625 (1.9%) |

| Information | 144,750 (4.2%) |

39,033 (8.2%) |

$216,390 (+$133,333) |

$8,433 (6.8%) |

| Information (less Software publishers) |

74,583 (2.1%) |

19,808 (4.1%) |

$162,140 (+$79,083) |

$7,631 (9.8%) |

| Software publishers | 70,167 (2.0%) |

19,225 (4.0%) |

$272,052 (+$188,995) |

$9,133 (5.3%) |

| Finance and Insurance | 100,083 (2.9%) |

283 (0.1%) |

$102,636 (+$19,579) |

$1,472 (1.7%) |

| Management of Companies & Enterprises | 44,575 (1.3%) |

9,858 (2.4%) |

$123,702 (+$40,645) |

$1,784 (1.7%) |

| Total/Average | 493,250 (14%) |

91,183 (20%) |

$125,442 (+$44,828) |

$2,722 (2.8%) |

Sources: 1) Employment Estimates (WA-QB, not seasonally adjusted) through December 2019 (preliminary), and 2) Covered Employment (QCEW) through June 2019 (preliminary), shown as annualized four-quarter rolling averages, with wages expressed in 2019 dollars using CPI-U-RS (estimated). 2018-19 Retail Trade (less Nonstore retailers) and Nonstore retailers wage data is estimated based on overall sector trend.

Sluggish wage growth and massive economic inequality aren’t the only economic headwinds facing Washington’s working families. Even after adjusting for inflation, costs are going up for critical needs like rent (or home ownership), health care, child care, and higher education. And to top it off, Washington’s low- and middle-income households pay a far higher share of their income in taxes than do those with higher incomes.

These trends aren’t just making everyday life a struggle for people – they’re making it impossible for many Washington households to build even a modest measure of economic security.

It doesn’t have to be this way. During the 2020 legislative session now underway, state and local leaders have the chance to make reforms that a) make Washington’s tax system more equitable, and b) promote increased investment in public policies that build and protect economic security for our families and communities. That includes: ramping up construction of affordable housing, tamping down out-of-pocket costs for health care, lowering the cost of child care by increasing subsidies for providers, teachers and families, and reducing tuition for public higher education, to name just a few!

Otherwise, when the next recession comes — as it inevitably will — it’s going to hit harder and hurt more than it needs to.

[1] Based on EOI analysis of Washington State Employment Security Department data: 1) Employment Estimates (WA-QB, not seasonally adjusted) through December 2019 (preliminary), and 2) Covered Employment (QCEW) through June 2019 (preliminary), shown as annualized four-quarter rolling averages, with wages expressed in 2019 dollars using CPI-U-RS (estimated).

[2] “Wages” include only hourly or salaried remuneration to employees.

[3] Wage and job figures for high-employment sectors based on EOI analysis of Washington State Employment Security Department data: 1) Employment Estimates (WA-QB, not seasonally adjusted) through December 2019 (preliminary), and 2) Covered Employment (QCEW) through June 2019 (preliminary), shown as annualized four-quarter rolling averages, with wages expressed in 2019 dollars using CPI-U-RS (estimated).

[4] Wage and job figures for high-employment sectors based on EOI analysis of Washington State Employment Security Department data: 1) Employment Estimates (WA-QB, not seasonally adjusted) through December 2019 (preliminary), and 2) Covered Employment (QCEW) through June 2019 (preliminary), shown as annualized four-quarter rolling averages, with wages expressed in 2019 dollars using CPI-U-RS (estimated).

More To Read

August 10, 2021

New State Programs May Ease a Short-Term Evictions Crisis, but Steep Rent Hikes Spell Trouble

State and local lawmakers must fashion new policies to reshape our housing market

November 20, 2020

We Can Invest in Us

Progressive Revenue to Advance Racial Equity