Introduction: Program overview and history

Washington’s Paid Family & Medical Leave program (PFML) launched in January 2020, the same month that the nation’s first COVID-19 case was identified in the state. During its first two years, PFML provided benefits on 262,500 claims from people welcoming a new child or coping with serious illness or family military deployment. While there have been hiccups in program implementation, the program has provided time and economic security when people needed those most. Participants have described the program as “life-changing” and “a godsend.” It remains highly popular with both workers and employers.[1]

In 2017, Washington adopted PFML in a politically divided legislature, based on policy negotiated by members of the Washington Work & Family Coalition, which had advocated for PFML for over 15 years, business lobbyists, and a bipartisan group of legislators.[2] Premium collection began in 2019 and benefits in 2020. Washington was just the fifth state in the U.S. to implement a full PFML program and the first to build a new program fully from scratch. At this writing there are eight jurisdictions operating PFML programs and four more in the process of implementing them.[*] Additional states are also considering adopting programs. The outlines of a federal PFML program were approved by the U.S. House in 2021 as part of the “Build Back Better” package, but stalled in the Senate.[3]

Washington state’s program provides up to 12 weeks of medical leave benefits for people with their own serious health condition and 12 weeks of family leave for welcoming a new child, caring for a family member with a serious health condition, or coping with a family member’s military deployment.[4] “Family members” originally included a set list of relatives, but legislation passed in 2021 extended the family definition to chosen family as well.[5] People needing both family and medical leave can take a combined total of up to 16 weeks in a 12-month period, with an additional two weeks available for people with pregnancy-related complications.

Employees and employers both contribute to premiums based on pay up to the Social Security wage cap. Premiums totaled a combined 0.4% of pay in 2019-2021 and 0.6% in 2022. Washington’s Department of Employment Security (ESD) administers the state PFML program, along with unemployment insurance and a portion of the future state long-term care program.[6]

The policies negotiated for Washington’s PFML program in 2017 were rooted in several key principles. These included:

- supporting healthy outcomes across the lifespan;

- providing equitable access to benefits, across income, gender, race, industry, and type of work;

- assuring portability and coverage of the modern, diverse workforce;

- promoting business success.

PFML eligibility is based on hours worked in Washington for any employer, or while self-employed for those who opt in, requiring a total of 820 hours worked during four consecutive quarters of the past five completed calendar quarters. In 2021, legislators approved a temporary additional qualifying period for people impacted by COVID, based on 2019 and early 2020 hours.[7]

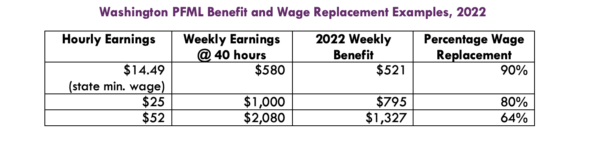

Benefits are progressive, based on the two highest earning quarters of the qualifying period. Wage replacement rates start at 90% for workers making less than half of the statewide average weekly wage and gradually diminishes to the maximum weekly benefit of $1,327 in 2022.[8] Employers are able to “top off” benefits, either as an additional benefit or by employees opting to use available sick leave or other paid time off to supplement PFML payments.

Source: EOI analysis based on ESD’s benefit calculator: https://paidleave.wa.gov/estimate-your-weekly-pay/

Employers are required to provide job protection for the full time an employee is on leave covered by PFML, but only for employees who generally meet FMLA requirements.[†] Washington’s Law Against Discrimination also protects jobs of people requiring medical leave related to pregnancy or childbirth, if they work for a non-religious organization with at least eight employees.[9]

Washington allows employers to provide equivalent benefits themselves or through insurance products rather than participate in the state program. Employers must apply for and receive state approval to operate these “Voluntary Plans.” In 2021, 277 employers had been approved for Voluntary Plans, covering 3% of the state workforce but 13% of wages. The list of VP employers has been considered confidential but will be public beginning in June 2022 based on Senate Bill 5649 passed in early 2022.[10]

Employers with fewer than 150 employees can apply for and receive small grants to help cover replacement costs when an employee takes PFML. The ability to apply for these grants was delayed until late 2020, but firms could file retroactively. About 250 small employers received grants for 2020 and 2021, over half of them for calendar 2020.[11]

To facilitate ongoing program evaluation and improvement, the original legislation required the program to collect demographic data (the application form requests but does not require this information), make annual reports to the legislature, and convene an advisory committee with equal numbers of employee and employer representatives.[12] The legislation also requires ESD to conduct ongoing educational outreach.

Program Usage

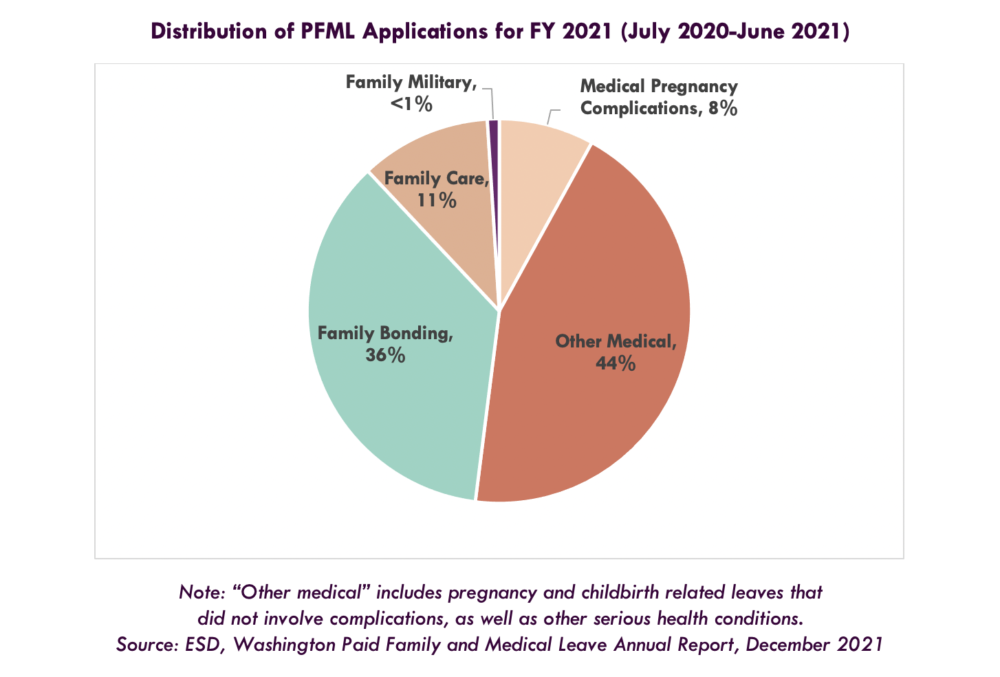

During 2020 and 2021, Washington’s PFML program provided benefits to 262,500 claimants. Because some people had more than one claim – both medical and family leave following childbirth, for example – this total includes 207,153 unique individuals.[13] Washington’s labor force through that period was about 3.8 million.[14] An initial large surge of applications came in when the program first launched in January 2020. The number of new applicants tailed off for the next couple months, but since then has trended upward to about 17,000 per month at the end of 2021.[15] In 2020, 53% of claims were for family leave, which includes caring for an ill family member, responding to a family member’s overseas military deployment, or bonding with a new child. Of total claims for 2020, 9% were for bonding with children born or placed in 2019. Since mid-2020, family leaves have represented 48% of applications and 51% of claims.[16]

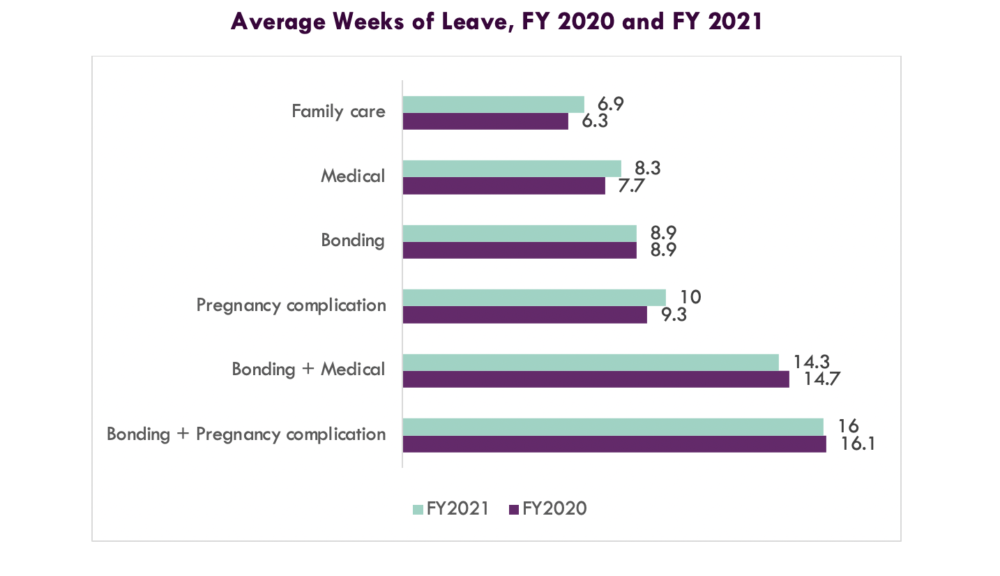

The average length of all leaves in FY 2021 was 10 weeks, including for those who combined family and medical leaves. A large majority of users did not take the maximum amount of leave.[17] Average lengths of leave were similar for people identifying as men or women who took only medical leave or leave to care for a seriously ill family member. Among those who took only bonding leave, women averaged 10.5 weeks compared to 8 for men; 63% of women who took leaves for either bonding or pregnancy complications combined bonding and medical leaves, both with and without pregnancy-related complications, for longer leaves.[18]

Note: For leaves begun in fiscal year with claim years ending by Sept. 30 of that year.

FY 2020 includes Jan.–Jun. 2020; FY 2021 includes Jul. 2020-Jun. 2021

Sources: ESD, Washington Paid Family and Medical Leave Annual Reports, 2020 and 2021

Possible impacts from COVID-19 pandemic

The impact of the COVID pandemic on program use is difficult to determine. Washington’s program has no pre-pandemic baseline. People likely took both family and medical leaves because of the disease itself, but while the medical certification form asks for a brief description of the diagnosis, neither it nor the application required people to indicate use of leave specifically for COVID-19. At the same time, many discretionary and non-urgent surgeries were postponed, medical appointments were harder to get, and people also postponed regular screenings that might have diagnosed conditions such as cancer that would have required leave for treatment and healing.

The pandemic also significantly affected employment, both causing periods of mass unemployment and pushing some people out of the workforce altogether due to health and safety concerns or loss of childcare.[19] Washington’s PFML program does not require people to have a current job if they otherwise meet eligibility. Still, people may have assumed they would not be eligible if not currently working. About one million Washington workers collected unemployment benefits during 2020. The higher pandemic unemployment insurance benefits approved by Congress could have made UI a more attractive option for those people who may have been eligible for either UI or PFML. Pandemic relief checks to households and expanded child tax credits also bolstered family incomes. Employment disruptions and childcare scarcity continued into 2022. In December 2021, 70,000 fewer people were employed in the state than at the beginning of the pandemic.[20] All of these factors could have affected PFML uptake.

State legislation passed early in 2021 allowed people who lost work due to COVID to establish PFML eligibility based on work in 2019 and the first quarter of 2020, and allocated ARPA funds to cover the anticipated costs of those leaves.[21] As of late February 2022, 2,212 people had taken leaves based on that optional eligibility, claiming $11 million in benefits.[22] This take-up was much lower than projected. The reasons for lower take-up are unknown but could include insufficient outreach and the other sources of federal pandemic financial assistance to households. The additional eligibility period expired for new applicants in late March 2022, and the 2022 state supplemental budget repurposed $134 million of the funds originally set aside.[23]

Applicant Characteristics

ESD used both program data and 2019 American Community Survey microdata to compare program users to eligible workers. The resulting analyses provide a wealth of valuable data.[24] However, ESD did not include workers who are not estimated to meet the 820 hour eligibility threshold in these analyses, limiting our ability to fully assess equitable access to program benefits. Substantial research documents the variability of schedules and both racial and gender inequities in access to regular shifts for lower wage shift workers, suggesting that workers who do not meet the 820 hour threshold may disproportionately come from vulnerable groups.[25]

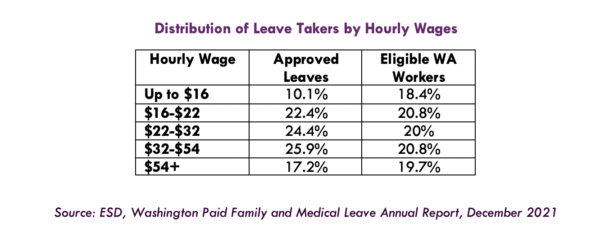

People making less than $16 per hour were least likely to use the program. These low-wage workers represented over 18% of eligible workers but took just 10% of leaves. Those making between $16 and $54 per hour took somewhat higher percentages of leaves than their share of eligible workers.

Employees at firms with fewer than 50 employees make up 29% of eligible workers, yet only 17% of program participants. Employees of larger firms may be more likely to take leave, both because they more often have legally-protected rights to job restoration and continuation of health insurance, and because their employers have HR departments which at least in some cases help inform employees about the program and walk them through the application process.[26] It is noteworthy, however, that employees making under $16 in large firms are even less likely to use the program than low-wage workers in small firms.[27]

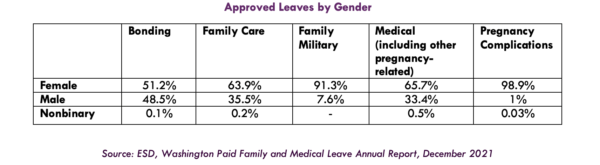

Applicants who identify as male or female have taken bonding leaves at close to equal rates, but women make the majority of other types of claims.[28]

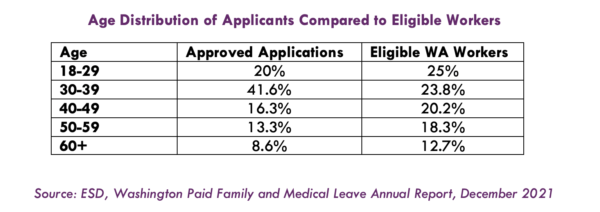

People aged 30 to 39 of all races and ethnicities are especially likely to take leave. This age group represents 24% of eligible workers, but takes 42% of all leaves and over 60% of leaves for bonding and pregnancy complications. Claims to care for seriously ill family members are distributed fairly evenly among 30 to 59 year olds, with workers from each of those decades taking about one-quarter of those leaves.[29]

Among 30 to 39 year old women, Asian, Pacific Islander, white, and Black women took similarly high rates of leave. Latina and Native American women in their 30s took leave at lower rates than other women in their age group, but at higher rates than other demographic groupings. Among men, Asian and white 30 to 39 year olds were more likely to use the program than other BIPOC 30 to 39 year olds. Asian men and women over 50 or under 30 were the least likely demographic groups to use the program relative to their representation in the Washington workforce.[30]

Early projections vs. actual demand

Program demand has differed from projections prior to the program’s launch in two significant ways. Washington PFML served far more people than expected in 2020 and 2021, and family leaves represented over half of leaves rather than the one-third anticipated. Modeling prior to program launch had assumed that demand would start low and build gradually over five years as people became more familiar with the program. The states that had added paid family leave to disability insurance programs prior to 2017 all experienced much lower than projected use of family leave during the first few years. However, extensive outreach by ESD, business associations, and advocates, plus the implementation of payroll premium collections in 2019 contributed to awareness among both employers and employees in Washington from the outset.

The different political and social landscape and the greater prevalence of social media when Washington’s program launched may also have increased people’s awareness of the program compared to the experience in pioneering states. Moreover, Washington’s program also launched with higher levels of wage replacement for low- and moderate-income workers than other state programs in existence at that time, making leave more affordable for financially strapped families.[31] During the first six months of 2020, the program paid claims to 33% more people than expected – 48,000 rather than 36,000.[32]

Higher than expected demand resulted in lengthy delays in processing applications over the first several months of 2020. ESD moved quickly to hire more permanent staff and brought in some temporary help, at the same time that employees transitioned to primarily remote work due to COVID. Typical times to process initial applications fell from ten weeks or more through the early spring to two weeks by the end of June 2020.

Lengthy telephone hold times and frequently dropped calls remained a serious problem that only began improving during the final months of 2021. ESD had hoped that faster processing of claims, improvements to the application and approval processes, and provision of information on the program’s website would sharply reduce the number of calls, but in reality, many people find aspects of the program confusing and applicants often need one-on-one help to resolve problems or deal with their specific situation. After repeated urging by Advisory Committee members and additional funding authorization provided in the 2021-23 biennial state budget, ESD stepped up staffing levels again during the last months of 2021, both to handle increasing application levels and get the phones under control. Phone hold times averaged under 10 minutes rather than over one hour by the end of 2021 and have continued to decline in 2022 to under 5 minutes. The four to five week gap between the time someone submits an application and they receive their first benefit payment continues to be a problem, however.[33] This gap between initial application and benefit receipt is especially hard for lower wage workers and those living paycheck to paycheck or unemployed.

The PFML program had 167 FTE staff in January 2020, including 98 on the customer care team (plus 83 additional contractors mostly in startup IT roles). By July 2020, the program had 307 staff, including 234 customer care team members, and by December, 360 total staff with 284 providing customer care.[34] At the end of 2021, the program was in the process of hiring and training 126 additional FTEs. Even with this expanded staffing, administrative costs remain low, representing 4.3% of total program expenditures for calendar 2021, and 4.6% for the first quarter of 2022.[35]

Higher than expected proportionate use of family leave

Family leaves have represented about half of the total claims, a higher percentage than the one-third projected by modeling prior to program launch.[36] Again, a combination of factors may be at play, including higher levels of awareness in Washington compared to earlier state programs that PFML covered care for ill family members in addition to parental and medical leaves; the fact that Washington covered extended family from the start, including siblings, grandparents, grandchildren, and in-laws; and the uptake of bonding leaves by Washington fathers. Medical leaves in Washington may have been reduced compared to the four earlier state programs because it was the first state program to draw on the FMLA definition of serious health condition rather than focusing eligibility on an inability to perform customary work. In addition, while Washington’s program allows people to take leave intermittently, they must take a minimum of 8 consecutive hours of leave (including over consecutive shifts) in any week to receive benefits. This requirement restricts the use of the program for some treatment regimens and chronic conditions that may need shorter periods of time off. COVID could have been an additional factor, both increasing numbers of seriously ill family members and decreasing medical leaves for surgeries and other treatments that were postponed.

The different histories of the pioneering state programs and Washington’s PFML program likely also affected the balance of family and medical leaves, especially around pregnancy and childbirth. California, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island all had decades-old disability programs that began covering pregnancy and childbirth related medical leaves in the 1970s. When these programs added bonding and other family leave, beginning with California in 2004, taking 6 to 10 weeks of disability leave for uncomplicated pregnancies and deliveries was already a well-established norm. California and New Jersey also initially limited family leaves to six weeks, and Rhode Island to four, while allowing 26 to 52 weeks of medical leave. Many birthing parents in these states continued to take their disability leave and then add on the allowable amount of bonding leave. Washington did not have this established norm of relying first on disability leave. Washington also allowed 12 weeks for bonding from the start.

Moreover, ESD failed to clearly and consistently communicate that people were eligible for medical leave to recover from uncomplicated vaginal childbirth and healthy pregnancies, as well as for the pregnancy-related complications that could trigger access to two additional weeks of leave. Women and health care providers often consider pregnancy and childbirth as healthy, rather than as “serious health” conditions. Many new parents and even midwives and medical doctors were unaware that someone giving birth without complications was allowed to combine medical and family leave for a total of 16 weeks. An application process that requires two separate applications for a birthing parent to take both medical and family leave, and the fact that for most of the program’s history people had a hard time getting through on the phone to ask questions, compounded the problem.

ESD analysis of women PFML customers who took medical leaves related to pregnancy and/or bonding leaves, excluding 2019 births, showed that 42% took only bonding leave, 11% took only pregnancy complication leave, and 46% took a combination of family and medical leave. In a follow-up survey of those who took only bonding leave, 61% said they knew they could also take medical leave. Reasons they said they didn’t varied: 22% said they didn’t want or need to, 11% used additional employer-provided leave instead, and 10.5% were concerned about job protection or couldn’t afford to. Others thought they did take medical leave, were denied or misinformed, or found the process too difficult.[37]

Consequences of underestimating initial demand:

Inequitable access

Washington’s PFML program started out understaffed in part due to higher than predicated demand, but also because decades of ideological attacks on government have resulted in largescale underfunding of public services and barebones staffing levels for many public services. The political realities of trying to pass a big new program through an often contentious partisan process encourages supporters to minimize staffing and administrative costs in order to avoid the label of big government. The resulting understaffing means slow customer service, inability to respond quickly to unexpected circumstances or crises such as a worldwide pandemic – and further loss of public confidence in government services.

Political realities and human need also push policymakers to establish the earliest possible launch dates for new PFML programs. Washington’s program began providing benefits with functional technology, but with an application and claims process that was rather clunky for customers and initially required some manual processing by staff, which slowed things down further. More resources and staffing during the implementation process could have eased this situation considerably.

Underestimating initial demand and insufficiently staffing Washington’s PFML program have had real consequences on people’s lives and undermined achieving the goal of equitable program access. It is clear from multiple sources that overall, Washingtonians greatly appreciate PFML. Still, both workers and businesses have faced challenges with the program.[38] The lengthy delays in processing applications during the first half of 2020 caused enormous financial and emotional stress for people who were already in the midst of health emergencies or family transitions. Some people gave up waiting and returned to work because they needed the income. Low wage workers and workers without a strong sense of job security need to know their leaves will be approved and claims for benefits will be paid quickly before they can risk scheduling a surgery or taking leave to care for a loved one. Employers that want to support their workers with wrap-around benefits also need to know how much leave and how much pay people will receive. The difficulty that people have had getting through on the phones for most of the program’s existence compounds the challenges both workers and employers have faced.

People whose language proficiency is in a language other than English have been especially challenged by unreliable phone access and slow processing of claims. While the PFML website includes information in 15 languages in addition to English and telephone assistance is available in multiple languages, the online application remains available only in English. Paper applications are available in other languages, but take longer to process initially, and ESD requires people who submit paper applications to also submit their weekly claims for benefits by telephone or paper rather than online, further slowing the receipt of benefit payments.

Consequences of underestimating initial demand:

Impacts on premiums

The table of bipartisan legislators and stakeholders who negotiated the initial PFML policy design agreed to shared premiums, with employees responsible for 63% of the total and employers responsible for 37%. Employer representatives also requested that employees pay the full family leave premium and that employer contributions be dedicated to employee medical leaves. With family leave assumed to be one-third of leaves, the law passed that year specified that workers would pay 100% of family leave premiums and 45% of medical leave premiums, and employers would pay 55% of medical premiums. Companies with fewer than 50 employees would not be required to pay the employer share.

The law also established payroll premiums for calendar years 2019 and 2020 totaling 0.4% of pay up to the Social Security wage cap. Premiums for calendar year 2021 and beyond would be set according to a fixed table and the ratio achieved by dividing the trust fund balance on September 30th by total covered wages of the prior fiscal year (July-June). According to that formula and table, premiums stayed at 0.4% for 2021 and rose to 0.6% in 2022.

Workers are paying almost all of that higher premium level. This is because the law also provides that the percentage of the total premium paid by employees and employers will adjust annually beginning in 2022 based on the balance of family and medical leaves during the previous fiscal year. In 2022 employees are responsible for 73% rather than 63% of the premium. In 2019 and 2020, employees contributed 0.25% of pay and employers the remaining 0.15% of pay. In 2022, employees are contributing 0.44% of pay, and employers 0.16%.[39]

Premium setting and the PFML trust fund

In January 2022, ESD announced that they might face cashflow issues with the PFML trust fund in March or April. Employers submit premiums and data on employee wages and hours quarterly, with premiums for the first calendar quarter due at the end of April. Clearly, higher than expected demand, the impacts of the pandemic on employment, and continued steady growth of the program all played a role in the shortage of funds. However, the premium setting methodology established in the original statute is a major contributor. The formula was designed to keep premiums as low as possible and to prevent a large buildup in the trust fund that some future legislature might see as an attractive source of revenue for other purposes. The failure to include either a calculation of the projected amount needed to cover the next year’s benefits or a reserve fund to cover short-term cash flow issues proved problematic, especially in the context of a still growing program. A large reserve had accumulated in the fund with the premiums collected during 2019 before benefits launched, but that resulted in premiums for 2021 being set at a level that would eat through the reserve.

Fortunately, the legislature had time to act during its regular 2022 session. It also had funds at its disposal because the state’s general fund revenues over the previous year had been stronger than projected when the 2021-23 budget was enacted, and some federal COVID relief dollars remained unallocated. The legislature set aside $350 million of state general funds as a separate PFML reserve account in the supplemental budget adopted in March. In addition, it ordered an actuarial study and established a taskforce to bring recommendations to the 2023 legislature on any adjustments needed to maintain long-term financial stability for the program.[40]

Continuous improvement

As an entirely new program, policymakers and advocates understood from the start that it would require careful monitoring and ongoing adjustments to both program administration and policy in order to achieve the goals of healthier outcomes and financial resilience for workers and employers across the state.

Administratively, substantially ramping up customer service staffing over the program’s first two years is beginning to pay off in better experiences for program users, but more remains to be done. Ultimately, sufficient staffing should boost equity and provide better outcomes for everyone, especially for low-wage and other vulnerable workers and families. Lack of sufficient staffing for much of 2020 and 2021 resulted in lengthy wait times and high levels of stress for people desperate for their benefits, and some people missing altogether the opportunity to support a dying parent or be with their child in the NICU. It also meant that some program components were slow to come online, including the small business grant program, which began accepting applications only at the end of 2020 and would have been especially valuable for the state’s small businesses dealing with COVID disruptions that year.

Speeding up the time from application to receipt of benefits, streamlining the application process for everyone, and providing better access for limited proficiency English speakers – including multi-lingual access to the online application – continue to be priorities for administrative improvement.

The state legislature also adopted several policy improvements in 2021 and 2022. Bills in 2021 expanded the family definition to include chosen family and added an additional qualifying period for people who lost work hours due to COVID. As originally introduced in 2021, House Bill 1073 reflected additional priority improvements identified by the Work and Family Coalition, including permanently reducing the hours worked requirement to meet the qualifying threshold and expanding rights to job protection and continuation of employer-provided health insurance to all workers after 90 days on the job.[41] Most other state programs already have much lower qualifying thresholds and/or provide job protection and continuation of health insurance for most workers.[42] BIPOC workers in Washington, in particular, have highlighted the need for legal protections to job restoration in order to feel comfortable using the full amount of PFML benefits they may be entitled to, given the continued prevalence of race-based stereotyping and discrimination in individual worksites.[43] However, those enhancements faced strong opposition from business lobbyists, including members of the PFML Advisory Committee, and were removed from the bill before final passage.[44]

Senate Bill 5649, introduced at the beginning of the 2022 legislative session, included more modest improvements that had near consensus support from all members of the Advisory Committee.[45] The original bill would have made PFML more compassionate and equitable by: allowing people to apply up to 45 days in advance of an anticipated qualifying event; extending family caregiving leaves up to 14 days after the death of a new child or family member for whom the worker was providing care; and allowing people to take medical leave during the first 6 weeks after giving birth without requiring additional medical certification.

Unfortunately, ESD’s announcement of a possible trust fund shortfall derailed some of those improvements, at least for 2022. Provisions to make it easier for someone giving birth to take medical leave remained, along with some other technical fixes, but the Senate committee removed advance applications in order to avoid additional staffing requirements and scaled back the extension of family leave after a death to seven days for new parents only. The committee also added actuarial analysis and a taskforce to recommend any changes needed for program financial stability. The bill passed both chambers of the legislature with overwhelming bipartisan support, indicating the high level of commitment to the program on the part of voters across the state and legislators of both parties.[46]

Looking ahead – Key Lessons

Washington’s experience in implementing a new comprehensive PFML program points to lessons for other states and a federal program. These include:

1. Everyone in the U.S. needs access to robust and comprehensive PFML: Paid Family & Medical Leave programs improve health and family economic security in both the short and long run. Washington workers and employers have enthusiastically embraced PFML. Even with frustrations over processing delays, inaccessible phone lines, and a still clunky application process, the program has served far more people during its first two years than anticipated. In addition to illness from COVID-19, people continued to have babies, get cancer, need surgeries, and have other health crises. During a time of unprecedented public health challenges and economic instability, PFML was more important than ever in supporting families with paid time off from work to heal and care for family, easing stress, and improving health outcomes.[47] Yet to date, only 12 jurisdictions have approved programs. Congress should move forward with adopting a national PFML program similar to the policy proposed by the U.S. House Ways & Means Committee for the Build Back Better package in 2021.[48]

2. Design for equity, but expect to need continuous improvements: Washington had the benefit of findings from earlier state programs when stakeholders drafted the new state policy in 2017. From the beginning the program included basic policy elements to promote equitable access to benefits and positive health outcomes, including progressive benefits that start at 90% wage replacement for lower-wage workers, shared premiums, 12 to 18 weeks of leave, an expansive definition of family, requirements for outreach, portability across employers and between jobs, and administration by the state, which allows for higher levels of transparency, accountability, and portability.

Since implementation, ESD, policymakers, and advocates have continued to identify priorities for both administrative and policy improvements. Some of these have been adopted, including a series of technology upgrades and staffing additions, adding chosen family, and allowing new parents to remain on leave following the death of their child – a proposal that originated from ESD customer care staff. All PFML programs will need to continue making administrative and policy improvements over time to ultimately achieve equitable outcomes.

3. Build in tools to evaluate equity: Washington is one of the few, if not the only, state PFML programs to collect demographic data from program applicants. Washington’s UI system is also one of the few that collects employee hours worked from employers, and this requirement was also included for PFML. These data, in addition to other data collected for program administration, allow for ongoing analysis of program use by race and ethnicity, gender identity, and hourly wage, as well as by age, workplace sector, and geographic region.[49] The initial legislation required annual reports to the legislature on these and other factors, and also established an ombuds office for the program and the Advisory Committee composed of worker and employer representatives, providing additional layers of program oversight and feedback.[50]

4. Staff for high-quality customer service and equitable access: Lack of sufficient staffing over the entire first two years of Washington’s PFML program created barriers to access for everyone. It prevented timely application processing and delivery of benefits, deterred some people from applying altogether, and frustrated employers. Almost by definition, someone who needs family or medical leave has limited capacity to navigate complex systems without assistance or spend hours trying to get through on the phone. Lower-wage workers, those with limited access to reliable internet or computers, and limited proficiency English speakers have been the most harmed. These and other more vulnerable workers need certainty that they will receive benefits, quick turnaround time on applications and speedy delivery of benefits, customer support that is accessible, and access to materials and customer support in multiple languages. Even with greatly expanded staffing, administrative costs represent less than 5% of Washington’s total program expenditures. Despite political pressures and the prevalence of anti-government bureaucracy rhetoric, policymakers should be prepared to make the investments in staffing that will allow programs to succeed in their missions.

5. Anticipate that new programs may have higher take-up rates than initially experienced by California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island: Washington administrators and advocates were surprised by a higher than expected number of applications in the program’s first year, given the lack of awareness about family leave in the states that had added on to disability programs. The additional buzz from passing a whole new program and instituting a new payroll tax as Washington and states that followed have done, outreach by ESD and a variety of stakeholders, the spread of news through social media, and heightened awareness of PFML in general due to national debates and media attention on the issue, as well as attention to equitable program design, likely all contributed to this higher uptake. New state and federal programs should be prepared to see similarly high take-up rates from the beginning.

Notes:

[*] California, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and New York had the first programs, adding family leave to temporary disability insurance programs that had been in place since the 1940s. The District of Columbia, Massachusetts, and Connecticut implemented programs after Washington. Oregon and Colorado are setting up programs that have been approved. Maryland and Delaware approved new programs in April 2022. For a comparison of program policies, see A Better Balance, https://www.abetterbalance.org/resources/paid-family-leave-laws-chart/

[†] Job protection in the PFML program is required if the employer has at least 50 employees in the state, and the employee has been with the employer at least 12 months and worked at least 1,250 hours in the previous year.

[1] For worker response to the PFML program, see Marilyn Watkins, “Responses of BIPOC Workers to Washington’s PFML Program,” May 2021, https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/research/post/responses-of-bipoc-workers-to-washingtons-paid-family-medical-leave-program/; and Washington Employment Security Department, Washington Paid Family and Medical Leave Annual Report, December 2020, https://esdorchardstorage.blob.core.windows.net/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/2020Paid-Leave-Program-Report.pdf

[2] See Marilyn Watkins, “The Road to Winning Paid Family & Medical Leave in Washington,” November 2017, Economic Opportunity Institute, https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/research/post/the-road-to-winning-paid-family-and-medical-leave-in-washington/

[3] Vicki Shabo, “Key Elements of the Build Back Better Act’s Paid Family and Medical Leave Proposal Explained,”

New America Foundation, Nov. 12, 2021, https://www.newamerica.org/better-life-lab/blog/key-elements-of-the-build-back-better-acts-paid-family-and-medical-leave-proposal-explained/. A more robust and impactful federal plan closer to those operated by states was approved by the House Ways & Means Committee: Subtitle A – Universal Paid Family and Medical Leave Section-by-Section, https://waysandmeans.house.gov/sites/democrats.waysandmeans.house.gov/files/documents/Section-by-Section_subtitleAE.pdf

[4] In Washington’s PFML law, “serious health condition” and “military exigency” follow closely the definitions in the federal Family & Medical Leave Act (FMLA). Revised Code of Washington 50.A.05, https://app.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=50A.05.010

[5] The definition now includes: “”Family member” means a child, grandchild, grandparent, parent, sibling, or spouse of an employee, and also includes any individual who regularly resides in the employee’s home or where the relationship creates an expectation that the employee care for the person, and that individual depends on the employee for care. “Family member” includes any individual who regularly resides in the employee’s home, except that it does not include an individual who simply resides in the same home with no expectation that the employee care for the individual.” Revised Code of Washington 50.A.05, https://app.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=50A.05.010

[6] Washington state has adopted the nation’s first public long-term care insurance program. ESD will collect payroll premiums and coordinate with other state agencies on additional aspects of program administration. For more information, see https://wacaresfund.wa.gov/.

[7] Washington State Legislature, HB 1073 (2021), https://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?BillNumber=1073&Initiative=false&Year=2021

[8] Washington’s benefit formula provides 90% of wages below 50% of the state average weekly wage (AWW), plus 50% of wages above 50% of AWW. The maximum weekly benefit is set at 90% of AWW.

[9] For more on WLAD protections, see Washington Administrative Code 162.30.020, https://app.leg.wa.gov/WAC/default.aspx?cite=162-30-020; and Washington Human Rights Commission, https://www.hum.wa.gov/employment

[10] Washington State Legislature, SB 5649 (2022) homepage, https://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?BillNumber=5649&Year=2021&Initiative=false

[11] Washington Employment Security Department, Washington Paid Family and Medical Leave Annual Report, December 2021, https://media.esd.wa.gov/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/2021-paid-family-and-medical-leave-annual-report-to-legislature.pdf

[12] Annual reports to the legislature can be viewed here: https://esd.wa.gov/newsroom/legislative-resources. Information on the advisory committee, along with monthly meeting notes and presentations with program, are available here: https://paidleave.wa.gov/advisory-committee/

[13] ESD Leave and Care Division data.

[14] Washington Employment Security Department, Monthly Employment Report, January 2022, https://media.esd.wa.gov/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/labor-market-info/Libraries/Economic-reports/MER/MER%202022/MER-2022-01.pdf

[15] For recent program data, see PFML Advisory Committee meeting presentation for February 2022, https://paidleave.wa.gov/app/uploads/2022/02/2022.02.11-February-Paid-Leave-Advisory-Presentation.pdf

[16] ESD, Washington Paid Family and Medical Leave Annual Report, December 2021, https://media.esd.wa.gov/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/2021-paid-family-and-medical-leave-annual-report-to-legislature.pdf

[17] ESD, Washington Paid Family and Medical Leave Annual Report, December 2021, https://media.esd.wa.gov/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/2021-paid-family-and-medical-leave-annual-report-to-legislature.pdf

[18] Data compiled by ESD for claims begun in FY 2021 (July 2020-June 2021) and completed by September 30, 2021.

[19] For continued pandemic impacts on women in the workforce, see National Women’s Law Center, “Resilient but not recovered: After two years of the COVID-19 crisis women are still struggling,” Mar 2022, https://nwlc.org/resource/resilient-but-not-recovered-after-two-years-of-the-covid-19-crisis-women-are-still-struggling/

[20] Washington Employment Security Department, Washington Historical Employment Estimates, seasonally adjusted, viewed Mar. 21, 2022, https://esd.wa.gov/labormarketinfo/employment-estimates

[21] Washington State Legislature, HB 1073, https://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?BillNumber=1073&Initiative=false&Year=2021

[22] ESD, Advisory Committee Presentation for March 3, 2022, https://paidleave.wa.gov/advisory-committee/

[23] ESSB 5693 (2022), Conference Report, Statewide Summary and Agency Detail, p. 274-275, http://leap.leg.wa.gov/leap/Budget/Detail/2022/cohAgencyDetail.pdf

[24] ESD, Washington Paid Family and Medical Leave Annual Report, December 2021, https://media.esd.wa.gov/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/2021-paid-family-and-medical-leave-annual-report-to-legislature.pdf; and “Program Utilization Study,” May 2021, https://paidleave.wa.gov/app/uploads/2021/06/WA-Paid-Leave-Utilization_Report_May-2021.pdf

[25] ACS does not ask for total annual hours worked, so ESD used reported typical work hours to approximate which workers would meet PFML’s 820 hour qualifying threshold. For racial and gender bias in scheduling, see Daniel Schneider and Kristen Harknett, “Schedule Instability Matters for Workers, Families, and Racial Inequality,” The Shift Project, https://shift.hks.harvard.edu/its-about-time-how-work-schedule-instability-matters-for-workers-families-and-racial-inequality/

[26] See comments and discussion in Marilyn Watkins, “BIPOC Women’s Experience Using Washington’s Paid Family & Medical Leave Program,” May 2021, https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/research/post/bipoc-womens-experiences-using-washingtons-paid-family-medical-leave-program/

[27] ESD, Washington Paid Family and Medical Leave Annual Report, December 2021, https://media.esd.wa.gov/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/2021-paid-family-and-medical-leave-annual-report-to-legislature.pdf

[28] ESD, Washington Paid Family and Medical Leave Annual Report, December 2021, https://media.esd.wa.gov/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/2021-paid-family-and-medical-leave-annual-report-to-legislature.pdf

[29] ESD, Washington Paid Family and Medical Leave Annual Report, December 2021, https://media.esd.wa.gov/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/2021-paid-family-and-medical-leave-annual-report-to-legislature.pdf

[30] For additional details, see ESD, Washington Paid Family and Medical Leave Annual Report, December 2021, https://media.esd.wa.gov/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/2021-paid-family-and-medical-leave-annual-report-to-legislature.pdf

[31] For recent program data, see PFML Advisory Committee meeting presentation for February 2022, https://paidleave.wa.gov/app/uploads/2022/02/2022.02.11-February-Paid-Leave-Advisory-Presentation.pdf

[32] ESD, Washington Paid Family and Medical Leave Annual Report, December 2021, https://media.esd.wa.gov/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/2021-paid-family-and-medical-leave-annual-report-to-legislature.pdf

[33] ESD, PFML Advisory Committee presentation, April 2022, https://paidleave.wa.gov/advisory-committee/

[34] For more detail on program startup, see Marilyn Watkins, “Preliminary Lessons from Implementing Paid Family & Medical Leave in Washington,” EOI, August 2020, https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/research/post/preliminary-lessons-from-implementing-paid-family-medical-leave-in-washington/

[35] ESD, PFML Advisory Committee presentation, April 2022, https://paidleave.wa.gov/advisory-committee/

[36] ESD, Washington Paid Family and Medical Leave Annual Report, December 2021, https://media.esd.wa.gov/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/2021-paid-family-and-medical-leave-annual-report-to-legislature.pdf

[37] ESD, PFML Advisory Committee presentation, October 2021, https://paidleave.wa.gov/app/uploads/2021/10/Paid-Leave-October-21-Advisory-Committee-Meeting-PPT.pdf

[38] See, for example, Watkins, “BIPOC Women’s Experiences Using Washington’s Paid Family & Medical Leave Program,” EOI, May 2021, https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/research/post/bipoc-womens-experiences-using-washingtons-paid-family-medical-leave-program/; and “Responses of BIPOC Workers to Washington’s Paid Family & Medical Leave Program, EOI, May 2021, https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/research/post/responses-of-bipoc-workers-to-washingtons-paid-family-medical-leave-program/

[39] ESD, Washington Paid Family and Medical Leave Annual Report, December 2021, https://media.esd.wa.gov/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/2021-paid-family-and-medical-leave-annual-report-to-legislature.pdf

[40] The taskforce and other program amendments are included in SB 5649 (2022), Washington State Legislature, https://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?BillNumber=5649&Year=2021&Initiative=false; the 2022 supplemental budget can be viewed at http://leap.leg.wa.gov/leap/budget/detail/2022/so2022Supp.asp

[41] Washington State Legislature, HB 1073 (2021) https://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?BillNumber=1073&Year=2021&Initiative=false

[42] A Better Balance, Comparative Chart of Paid Family and Medical Leave Laws in the United States, updated Mar. 24, 2022, https://www.abetterbalance.org/resources/paid-family-leave-laws-chart/. See also Bipartisan Policy Center, State Paid Family Leave Laws Across the Country, Jan. 13, 2022, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/explainer/state-paid-family-leave-laws-across-the-u-s/; and “State Family and Medical Leave and Job-Protection Laws,” 2019, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/State_FMLA_Factsheet_RV1-3.pdf

[43] Marilyn Watkins, “Responses of BIPOC Workers to Washington’s PFML Program,” May 2021, https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/research/post/responses-of-bipoc-workers-to-washingtons-paid-family-medical-leave-program/

[44] See Washington State Legislature, House Bill Report, HB 1073, Feb. 2021, https://lawfilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2021-22/Pdf/Bill%20Reports/House/1073%20HBR%20APP%2021.pdf?q=20220331125204

[45] Washington State Legislature, Senate Bill Report, SB 5649, Feb. 2022, https://lawfilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2021-22/Pdf/Bill%20Reports/Senate/5649%20SBR%20WM%20OC%2022.pdf?q=20220331125847

[46] SB 5649 (2022), Washington State Legislature, https://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?BillNumber=5649&Year=2021&Initiative=false

[47] Marilyn Watkins, “Responses of BIPOC Workers to Washington’s PFML Program,” May 2021, https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/research/post/responses-of-bipoc-workers-to-washingtons-paid-family-medical-leave-program/

[48] U.S. House Ways & Means Committee: Subtitle A – Universal Paid Family and Medical Leave Section-by-Section, https://waysandmeans.house.gov/sites/democrats.waysandmeans.house.gov/files/documents/Section-by-Section_subtitleAE.pdf

[49] Reports prepared by ESD on PFML include: 2020 PFML Annual Report to Legislature, https://esdorchardstorage.blob.core.windows.net/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/2020Paid-Leave-Program-Report.pdf; 2021 PFML Annual Report, https://media.esd.wa.gov/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/2021-paid-family-and-medical-leave-annual-report-to-legislature.pdf; PFML Program Report by Industry, https://media.esd.wa.gov/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/paid-family-and-medical-leave-annual-report-to-legislature-addendum.pdf; PFML State and Voluntary Plan Usage, https://media.esd.wa.gov/esdwa/Default/ESDWAGOV/newsroom/Legislative-resources/2021-voluntary-plan-report-to-legislature.pdf; PFML Program Utilization Study (May 2021), https://paidleave.wa.gov/app/uploads/2021/06/WA-Paid-Leave-Utilization_Report_May-2021.pdf

[50] PFML authorizing legislation can be found at: Revised Code of Washington, Title 50A, Family and Medical Leave, https://app.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=50A. The Advisory Committee page can be viewed at https://paidleave.wa.gov/advisory-committee/; and the Ombuds’ website is at https://paidleaveombuds.wa.gov/

More To Read

June 5, 2024

How Washington’s Paid Leave Benefits Queer and BIPOC Families

Under PFML, Chosen Family is Family

November 21, 2023

Why I’m grateful for Washington’s expanded Paid Family & Medical Leave

This one is personal.

February 10, 2023

Thirty Years of FMLA, How Many More Till We Pass Paid Leave for All?

The U.S. is overdue for a federal paid leave policy