Declining unionization, and race- and gender-based discrimination are increasing economic disparities in the state.

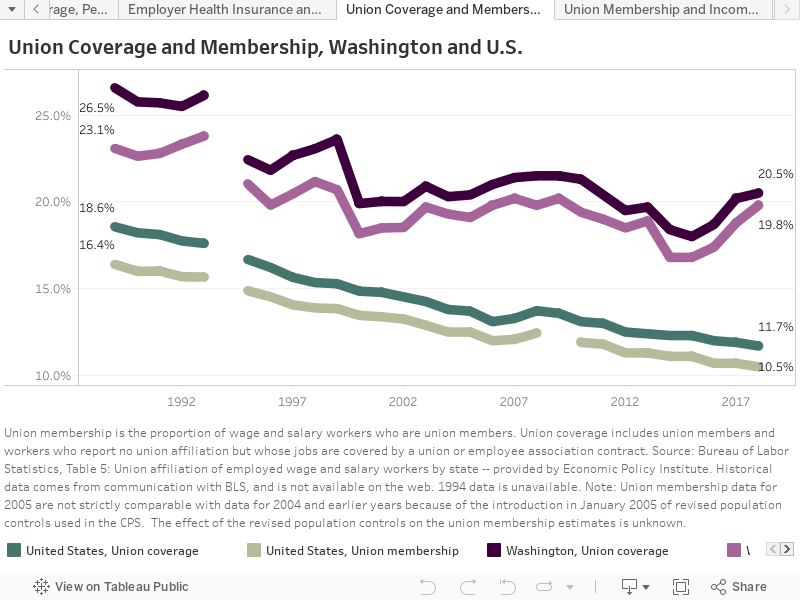

Declining Unionization

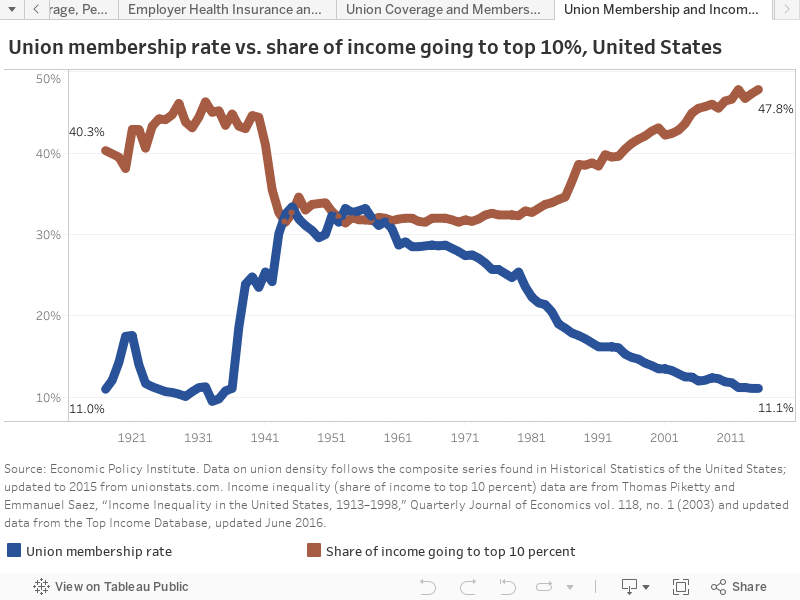

While no single factor is entirely responsible for the growth in inequality, declining unionization has been a contributing influence.[8] Following the passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935, the spread of collective bargaining led to decades of faster and fairer economic growth that persisted until the late 1970s.

Since the 1970s, however, declining unionization has fueled rising inequality and stalled economic progress for the middle class. Nationally from 1972 to 2007, one-third of the rise in wage inequality among men, and one-fifth of the rise in wage inequality among women, is attributable to declining unionization. Among men, the erosion of collective bargaining has been the largest single factor driving a wedge between middle- and high-wage workers.[9]

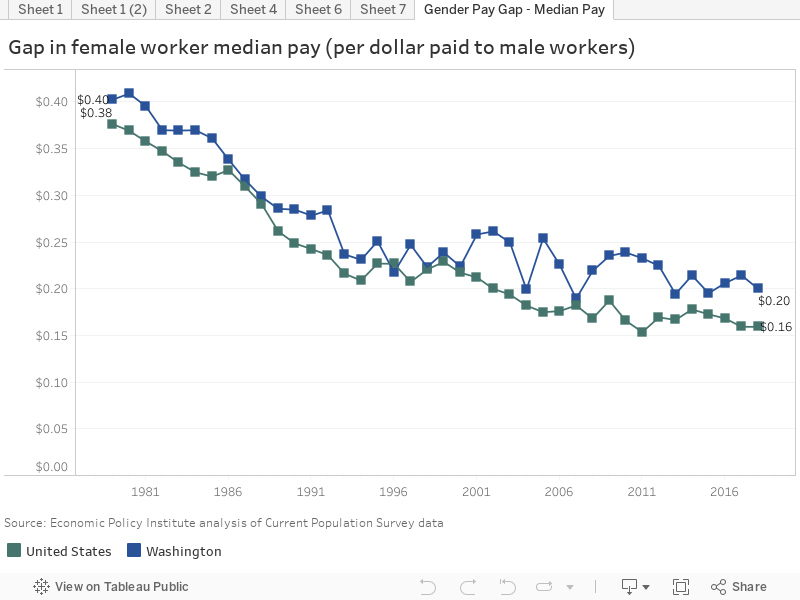

Gender Pay Discrimination

Another persistent source of income inequality is the gender pay gap. In Washington, a typical woman (or one earning median wage) is paid 22 cents less per dollar paid to a typical man.[10] While the gender pay gap has declined since 1979, the state has not made any significant or lasting progress in closing the gap since the late 1990’s.

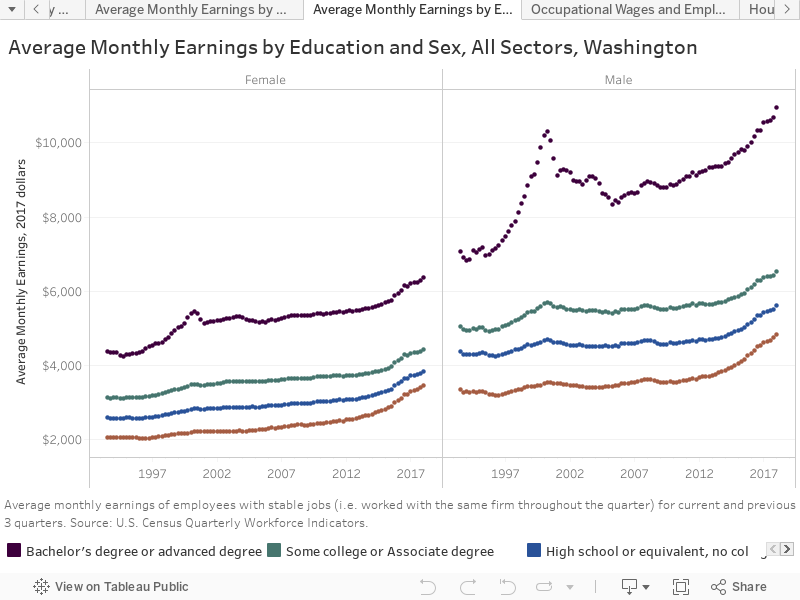

The gender pay gap is not an education gap – nor is it solely a product of having fewer women in some industries than others. At every level of education, women are paid less than similarly educated men – and the wage gap rises with additional education. The gap also exists in all industries – including those in which more women are employed than men.[11]

Gap in Average Monthly Wages versus Male Workers, All Industries, Washington

| Sector | Ratio of Female to Male Workers |

Gender Wage Gap (Average monthly wage) |

| Health Care and Social Assistance | 3.34 | $1,898 |

| Educational Services | 2.23 | $855 |

| Finance and Insurance | 1.67 | $3,520 |

| Other Services (except Public Administration) | 1.26 | $1,221 |

| Accommodation and Food Services | 1.16 | $279 |

| Management of Companies and Enterprises | 1.16 | $2,007 |

| Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation | 1.04 | $843 |

| All NAICS Sectors | 0.93 | $2,013 |

| Retail Trade | 0.92 | $1,452 |

| Real Estate and Rental and Leasing | 0.91 | $914 |

| Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services | 0.87 | $2,694 |

| Public Administration | 0.80 | $1,248 |

| Admin. & Support and Waste Mgmt. & Remed. | 0.71 | $969 |

| Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting | 0.56 | $736 |

| Information | 0.48 | $4,781 |

| Utilities | 0.44 | $2,264 |

| Transportation and Warehousing | 0.44 | $1,203 |

| Wholesale Trade | 0.43 | $1,680 |

| Manufacturing | 0.37 | $1,359 |

| Construction | 0.22 | $1,447 |

Source: U.S. Census Quarterly Workforce Indicators, Full Quarter Employment (Stable); monthly wage calculated as 3-quarter weighted average for 2017 Q1 to 2017 Q3.

Racial Pay Discrimination

The National Picture

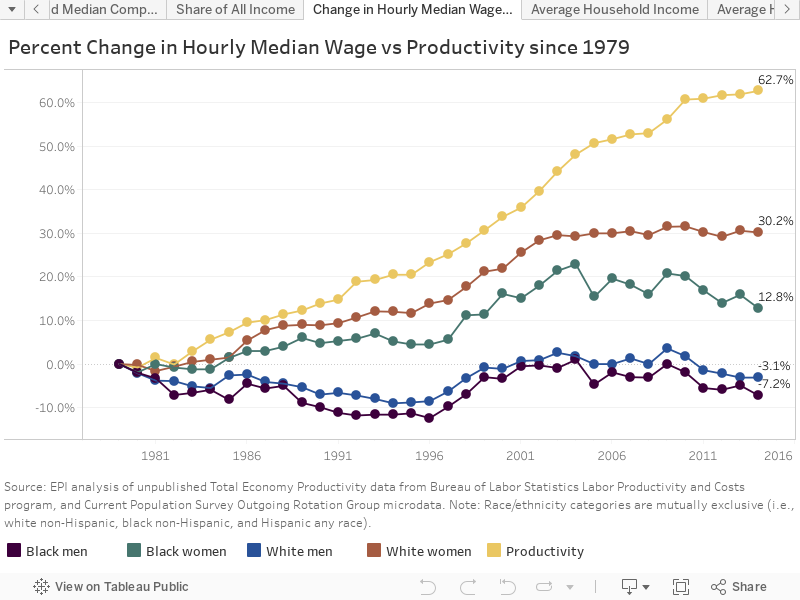

All demographic groups are experiencing growing income inequality and slowing growth in living standards. At the national level, since 1979 median hourly real wage growth has fallen short of productivity growth for all groups of workers, regardless of race or gender. However, these wage trends are markedly different for men than for women, and for blacks relative to whites.

Median hourly wages for both white and black men have fallen, with black men suffering larger losses (7.2 percent, compared a 3.0 percent loss for white men). While median hourly wages of black and white women have increased, white women’s wages grew much more (30.2 percent) than those of black women (12.8 percent).[12]

The Pacific Region

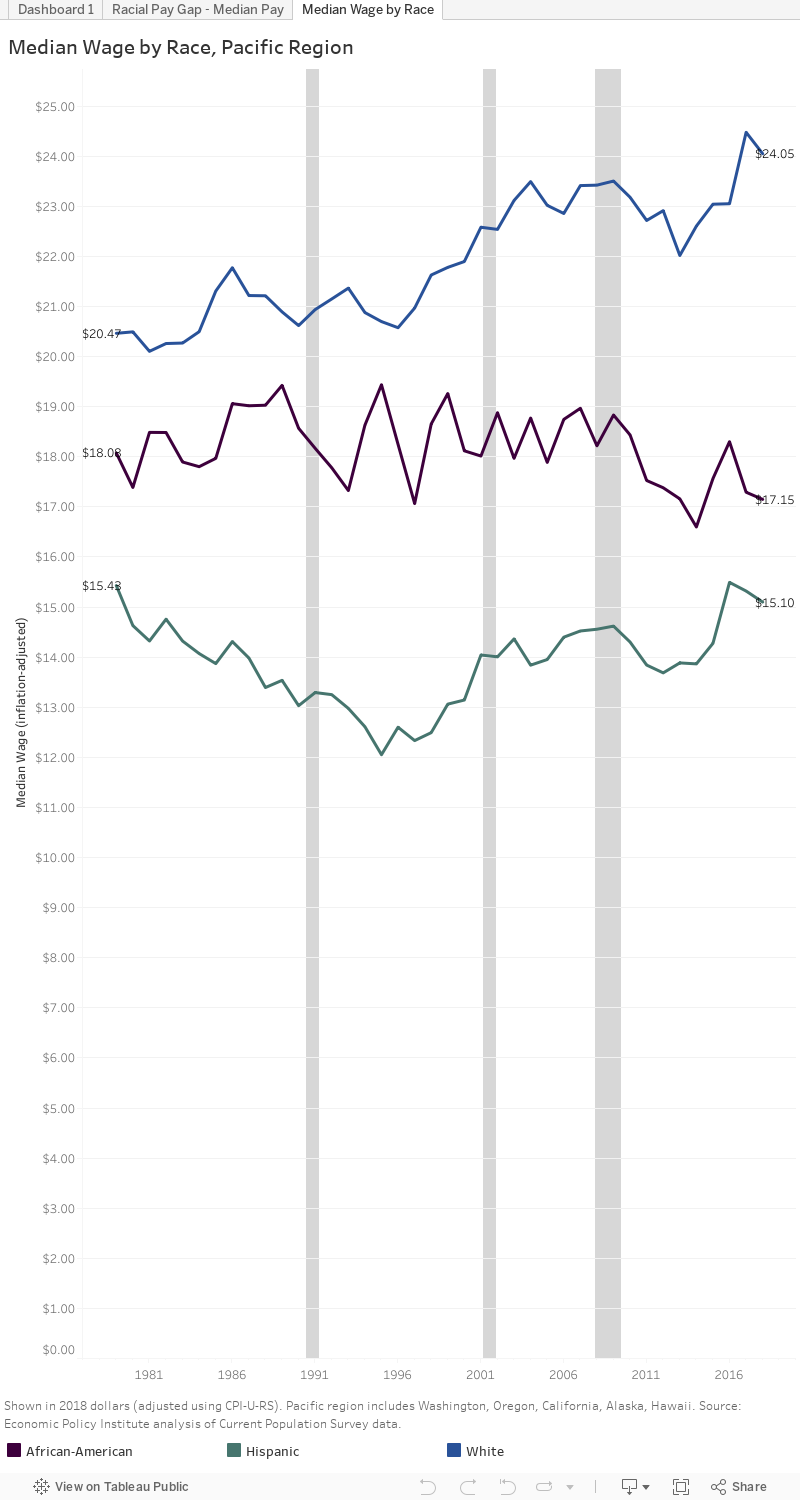

In the Pacific region of the U.S. (Washington, Oregon, California, Alaska, Hawaii), pay disparities by race and ethnicity have grown relative to 1979 levels. The median wage for White workers increased to $24.05/hour (+$3.58), while for Hispanic and Black workers it declined to $15.10/hour (-$0.33) and $17.15/hour (-$0.93), respectively.[13]

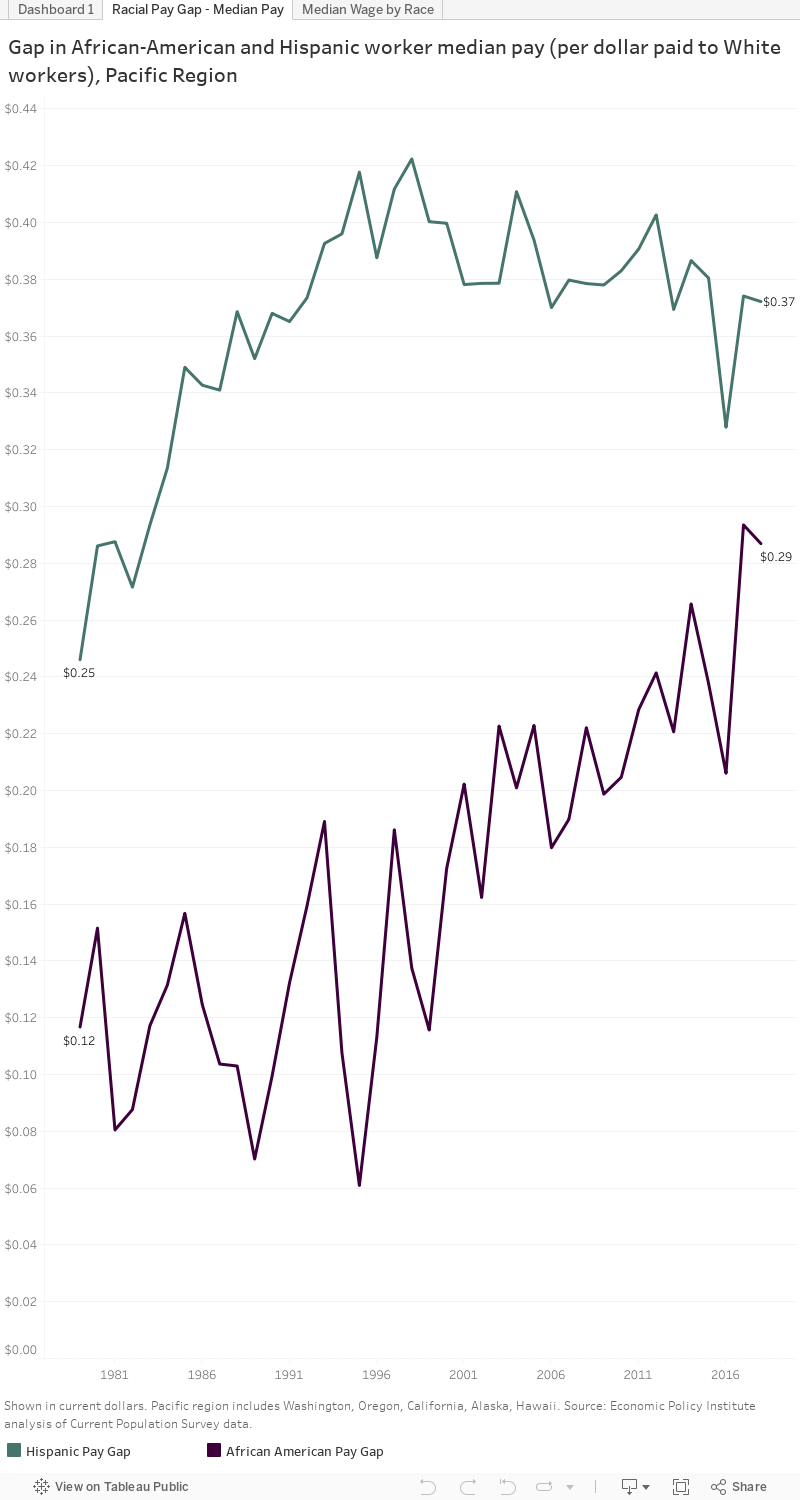

Put another way: in 2018 a typical (or median) Black worker was paid 29 cents less, and a Hispanic/Latinx worker 37 cents less, per dollar paid to a typical White worker. Since 1979, that gap has grown by 142 percent for Black workers, and for Hispanic/Latinx workers the gap has grown by nearly 50 percent.

Washington State

In Washington, the gap in average monthly wages between White workers and workers who are people of color grew dramatically between 1990 and 2017 (save for workers of Asian descent, a subset of whom are employed in very high-wage information, technology and professional sectors). In 2017 alone, the racial gap cost workers of color an average $12,228 to $20,838/year.[14]

Gap in Average Monthly Wages versus White Workers, All Industries, Washington State

|

Avg. monthly wage (2017 dollars) |

Gap in avg. monthly wage compared to White workers |

Equivalent yearly wage gap |

Increase in wage gap | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity |

1990 Q2 |

2017 Q2 |

1990 Q2 |

2017 Q2 |

1990 |

2017 |

|

| Amer. Indian/ Alaska Native | $2877 | $3961 | $833 | $1448 | $9996 | $17,376 | 74% |

| Asian | $3263 | $6551 | $447 | -$1142 | $5364 | n/a | n/a |

| Black or African American | $3112 | $3876 | $598 | $1533 | $7176 | $18,396 | 156% |

| Hisp./Latinx | $2614 | $3673 | $1096 | $1737 | $13,152 | $20,838 | 58% |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | $2816 | $3825 | $894 | $1584 | $10,728 | $19,008 | 77% |

| Two or More Race Groups | $3058 | $4390 | $652 | $1019 | $7824 | $12,228 | 56% |

| White (not Hisp./Latinx) | $3710 | $5409 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

Source: U.S. Census Quarterly Workforce Indicators, Full Quarter Employment (Stable), second quarter average monthly wages. Inflation adjusted to 2017 dollars using CPI-U-RS.

As with the gender pay gap, workers of color cannot educate themselves out of pay disparities. Nationally, as of January 2017, average hourly wages for White college graduates are far higher ($31.83) than for Black college graduates ($25.77) – and the national unemployment rate for Black college graduates was 4.0 percent, compared to 2.6 percent for White college graduates.[15],[16]

Footnotes

[8] Economic Policy Institute, “Union decline and rising inequality in two charts”, https://www.epi.org/blog/union-decline-rising-inequality-charts/.

[9] Economic Policy Institute, “How today’s unions help working people”, https://www.epi.org/publication/how-todays-unions-help-working-people-giving-workers-the-power-to-improve-their-jobs-and-unrig-the-economy/.

[10] American Community Survey 2017 1-Year Estimates, Sex by Industry and Median Earnings in the Past 12 Months for the Full-Time, Year-Round Civilian Employed Population 16 Years and Over, Washington State.

[11] Based on EOI analysis of U.S. Census Quarterly Workforce Indicators, Full Quarter Employment (Stable) wages and employment; monthly wage calculated as 3-quarter weighted average for 2017 Q1 to 2017 Q3.

[12] Based on Economic Policy Institute analysis of unpublished Total Economy Productivity data from Bureau of Labor Statistics Labor Productivity and Costs program, and Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata.

[13] Based on Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data.

[14] Based on EOI analysis of U.S. Census Quarterly Workforce Indicators, Full Quarter Employment (Stable), second quarter average monthly wages. Inflation adjusted to 2017 dollars using CPI-U-RS.

[15] Economic Policy Institute, “Racial gaps in wages, wealth and more: a quick recap”, https://www.epi.org/blog/racial-gaps-in-wages-wealth-and-more-a-quick-recap/.

[16] For a deeper review and analysis of the racial pay gap, see “Black-white wage gaps expand with rising wage inequality”, Economic Policy Institute, https://www.epi.org/publication/black-white-wage-gaps-expand-with-rising-wage-inequality/.

More To Read

October 14, 2025

Opportunity for many is out of reach

New data shows racial earnings gap worsens in Washington

January 17, 2025

A look into the Department of Revenue’s Wealth Tax Study

A wealth tax can be reasonably and effectively implemented in Washington state

January 6, 2025

Initiative Measure 1 offers proven policies to fix Burien’s flawed minimum wage law

The city's current minimum wage ordinance gives with one hand while taking back with the other — but Initiative Measure 1 would fix that