For a PDF, click here.

Background

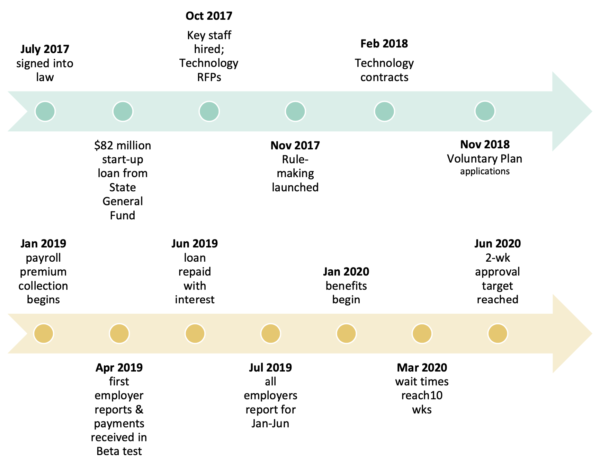

Washington is the fifth U.S. state to implement a comprehensive Paid Family & Medical Leave program, and the first to build the full program from the ground up. After a multi-year campaign and stakeholder negotiations, Washington’s legislature passed the program in 2017. Payroll contributions by employees and employers began in January 2019, and paid leave benefits began in January 2020.

Washington’s program allows workers to take up to 12 weeks, and in some cases up to 18 weeks, of paid leave in a year to care for a new child, seriously ill family member, their own serious health condition, or cope with a family member’s military deployment. Washington’s Employment Security Department (ESD) administers the program.[1]

The four states that implemented earlier programs – California, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and New York – added paid family leave to long-established temporary disability insurance (TDI) systems that covered workers’ own health conditions, including pregnancy and recovery from childbirth. Research has shown that these programs boost health and economic security, and reduce health and other disparities by race, gender, and income.[2] These positive outcomes have been achieved even though all four states experienced lower than expected demand for family leave in the first few years after the programs were expanded, in part because many workers did not know about the new benefits, wage replacement was often insufficient, and TDI was already providing some amount of paid leave for many birth mothers.

Summary of Key Lessons from Washington

Washington’s experience provides key lessons for stakeholders implementing or developing similar state or federal programs, including:

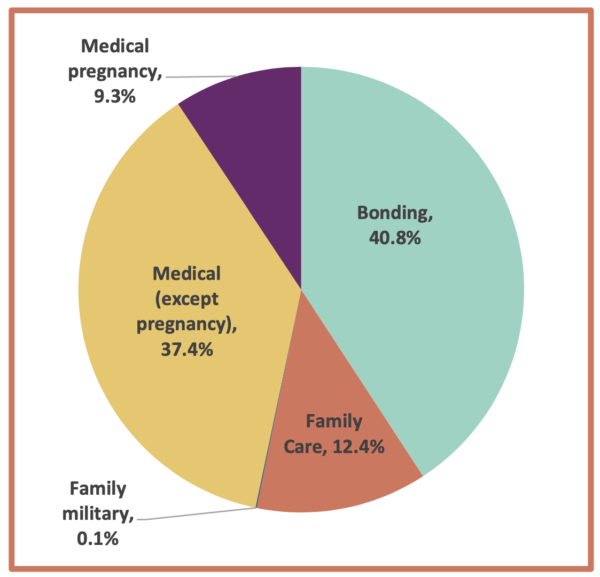

1. There is high demand for paid family and medical leave. In the first six months, Washington workers filed 85,000 applications for PFML benefits out of a total workforce of close to 4 million. New applications are coming in at a rate of 10,000-12,000 per month. Close to half are for the worker’s own serious health condition, about 40% are to care for a new child, and 12% are to care for another family member.

2. Washington received three times the expected number of applications in the first month and has continued to receive more than expected for the program’s first year of operation. The four states that had previously added family leave to temporary disability programs all experienced much lower than projected volumes in the first few years, with a gradual increase over time. Washington expected a similar slow start and was prepared to process about 6,000 applications a month. However, the program received a large influx of applications in the first weeks of January and volumes projected for the program’s second or third year in subsequent months.

3. Extensive research and building strong community buy-in prior to adoption contributed to Washington’s ability to adopt what was at the time the strongest PFML program in the country, with a focus on equitable access and inclusion. Community support and progressive benefits likely contributed to high take up rates. Preliminary demographic data show claimants’ racial and ethnic backgrounds roughly approximate the overall state population.

4. Regular communication and collaboration between program staff and stakeholders, including both worker and business representatives, contributed to broad dissemination of information about the program and a timely launch. Program staff have consistently sought public input, through a formal advisory committee that meets monthly, multiple public meetings during rulemaking, focus groups, and outreach to organizations and groups. Public input and collaboration have helped improve systems and avoid some – but not all – missteps.

5. A culture focused on customer service, flexibility, and continuous improvement within Washington’s Employment Security Department (ESD) has been key to timely launch of program elements and responding to unexpected events. Setting up a new program with new technology on a fixed timeline is always challenging, but was accomplished relatively successfully. Both the high volume of initial applications and the COVID-19 pandemic required ESD to make rapid improvements to processes and staffing changes after program launch. The responsive and transparent culture that ESD cultivated in the program team from the beginning made those responses easier.

6. Completing the rulemaking process more quickly and checking all assumptions with the advisory committee would have allowed earlier development of technology and better preparation for the volume of applications. In order to maximize opportunity for public input and focus quickly on parts of the program that needed to be implemented first, ESD divided rulemaking into multiple phases that ultimately stretched over two years. But stakeholder interest dwindled as the process dragged on, and some application processes could not be designed until rules were completed, allowing minimal time for input and testing of the final product or advance applications before program launch.

7. Public administration has assured transparency, accountability, and a focus on serving all workers and businesses. Both when implementation has been going smoothly and when problems have arisen, the fact that a public agency is administering the program has meant that stakeholders in Washington and others around the country have received timely information. Program staff understand the historic importance of their work and are eager to share what they learn. The backlog of applicants in early 2020 led to delays in people receiving benefits, but everyone entitled to benefits ultimately will get them – there is no profit motive to encourage denying benefits.

Program Statistics, January – June 2020

Application Types Feb-Jun 2020

Source: PFML Advisory Committee presentation July 16, 2020

New Applications by Type and Month, Jan. – Jun. 2020

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Total | |

| Bonding | 12,397 | 4969 | 6002 | 4774 | 4297 | 4383 | 36,822 |

| Family Care | 2687 | 1773 | 2244 | 1337 | 954 | 1123 | 10,118 |

| Family military | 40 | 19 | 11 | 11 | 6 | 8 | 95 |

| Medical (except pregnancy) | 7678 | 4945 | 5998 | 3819 | 3285 | 4340 | 30,065 |

| Medical pregnancy | 1825 | 1271 | 1338 | 1083 | 947 | 943 | 7,407 |

| Total | 24,627 | 12,977 | 15,593 | 11,024 | 9,489 | 10,797 | 84,507 |

Source: PFML Advisory Committee presentation July 16, 2020

During the program’s first six months, about 65% of applicants have been women with a median age of 33. Men account for about 40% of bonding, family care, and non-pregnancy medical claims.

The racial and ethnic breakdown of applicants has roughly reflected Washington’s population. Overall, 65% of applicants have been White/non-Hispanic (compared to 67% of state residents), 6% have been Black (compared to 4% of state population), 13% Latinx (compared to 13% of state population), and 9% Asian (compared to 9% of state population).[3]

How Washington Implemented Paid Family & Medical Leave

Washington PFML Implementation Timeline

1. Policy: Designed for Equity

Washington’s legislature adopted the PFML program in 2017, based on a policy negotiated by a table of stakeholders and a bipartisan group of legislators.[4] Washington deliberately crafted its program to promote equitable access and improve health and economic security outcomes, including by:

- Providing progressive benefits, with lower wage workers receiving 90% wage replacement and middle income workers 67% to 75% wage replacement;

- Ensuring portability between employers and during periods between jobs;

- Including multiple employers and contract work in establishing eligibility and typical wages;

- Including a broad range of family members, including grandparents, grandchildren, siblings, in-laws, and broad definitions of parent and child;

- Requiring ESD to conduct outreach about the program, collect demographic data from applicants so that outcomes could be measured, and make annual reports to the legislature;

- Establishing an advisory committee composed of both employee and employer representatives;

- Establishing an ombuds office with the ability to troubleshoot, conduct employee and employer surveys, and provide independent evaluations.

Nevertheless, the negotiated policy also includes factors that may undercut equitable access, including:

- A lack of job protection for people not already covered by the federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), meaning that people who work for employers with fewer than 50 employees, who have been on the job less than a full year, or who worked less than 1,250 hours the previous year will not be guaranteed their jobs back after PFML leaves – a provision likely to most negatively affect lower-wage workers;

- An 820 hour work requirement in the previous year (across any combination of employers, including self-employment);

- A minimum weekly claim amount of 8 consecutive hours of leave, which limits accessibility to people who work shorter shifts (although the consecutive hours can include multiple shifts);

- A one-week waiting period for leaves other than for bonding and family military exigencies.

Washington’s PFML program also includes elements that increased support from business associations and some large employers, but also complicated system development and implementation, including:

- Allowing employers to provide equal benefits through “Voluntary Plans,” with ESD approval and oversight (255 firms have been approved to provide Voluntary Plans as of July 2020 – 0.1% of the state’s employers);

- Allowing employers and employees with collective bargaining agreements in effect when the law took effect (October 2017) to remain outside the program until the contract reopened, expired, or was renegotiated;

- Not requiring businesses with fewer than 50 employees to pay the employer share of premiums, although allowing them to voluntarily pay those premiums;

- Providing grants to businesses with fewer than 150 employees that pay premiums and have employees taking leave.

Learning 1.1: Key actions prior to adoption contributed to Washington’s ability to craft and adopt what was at the time the strongest PFML program in the country, with a focus on equitable access and inclusion:

- Extensive input from impacted communities – Washington’s Work and Family Coalition, convened by the Economic Opportunity Institute and including leadership from labor and community-based organizations, and a core group of legislators worked on developing PFML policy and support over a number of years prior to 2017. Over that time, diverse communities and interest groups from across the state were asked to weigh in on principles and policy priorities, including unions, small business owners, low-wage worker organizations, BIPOC-led community organizations, LGBTQ groups, immigrant groups, professional women’s associations, health professionals, and military families.

- Research base – Attention to the research on outcomes from the four states with existing programs and connections of the Work and Family Coalition to the national movement, including through Family Values at Work and the Economic Analysis Research Network, combined with community input to forge solid policy principles and build on best practices.

- Early engagement of agency staff – The Coalition and legislators worked directly with Employment Security Department personnel over several years to establish relationships of trust, build agency understanding of the program’s goals, and draw on their expertise in program design and administration.

- Education and engagement of policymakers – The Coalition established strong relationships with legislators and within the Governor’s office and included them in community-based conversations prior to introducing legislation. As a result, a number of policymakers understood the type of program their constituents needed and why particular policy details were important. They were then better able to withstand pressures during the legislative session to compromise in ways that would have made the program less inclusive and focused on equitable outcomes.

- Broad support and base of power – The Coalition continuously worked to build support among voters and diverse communities. The success of a series of city council and voter initiative campaigns on paid sick days and minimum wage led by different coalition partners from 2011 through 2016 helped consolidate power and momentum for a strong and comprehensive policy administered by the state.[5]

Learning 1.2: While negotiating with organized business lobbyists and across party lines resulted in compromises that may reduce equitable outcomes, it also assured passage of the program in 2017 rather than some future date and generated goodwill in the business community. That goodwill has largely continued, so that business associations, as well as labor unions and nonprofit organizations, have cooperatively engaged with PFML staff in program implementation and outreach.

2. Estimating Costs and Building a New Agency

Washington State applied for and received a grant from the U.S. Department of Labor in 2015 which allowed the state to cost out several program design options. The modeling for the grant established a basis for ESD to be able to project usage and cost for the policy as it was passed in 2017.

ESD’s own experience administering the state’s Unemployment Insurance system provided a basis for estimating administrative costs for the program. Based on these estimates, ESD requested start-up funds of $82 million. The Legislature appropriated this money from the state’s General Fund as a loan, and ESD paid it back with interest after the first premium collections came in within the fiscal biennium. Actual start-up costs were lower than projected. ESD spent $63.2 million of the $82 million during the 2017-19 biennium.

ESD understood the historic importance of Washington’s PFML program and moved quickly to hire key staff. Many of the initial hires came from within state government, and a dedicated human resource specialist helped to speed up the state’s usual 6 to 8 week timeline for hiring. By early fall 2017, a program director, policy manager, technology manager, research manager, and contract specialist were on board. A second wave of hiring in fall 2017 included a communications manager, budget manager, lead trainer, organizational change manager, and other support staff.

The new PFML team sought advice from established state PFML programs, including California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island.

By April 2018 the program had 50 dedicated staff, and for Fiscal Year 2019 (July 2018-June 2019), the PFML program had 93.5 direct FTEs. The number of FTEs was expected to peak in FY 2020, with both start-up and a full complement of operations staff overlapping. With unexpectedly high initial demand for benefits in early 2020, ESD was forced to authorize overtime, borrow staff, contract out some work, and hire new staff to handle the unexpectedly high number of applications.

Staffing Levels for Washington PFML Program – Implementation Phase, FY 2019

| FY* 2019 FTEs | |

| Program Administration | 8.8 |

| Ombuds office | 1.3 |

| Communications & outreach | 6.3 |

| Operations (including customer care) | 39.5 |

| IT | 32.7 |

| Rules & policy | 4.9 |

| Total | 93.5 |

*Note: Fiscal year (FY) runs from July 1, 2018 to June 30, 2019

2020 Staffing for Washington’s PFML Program

| Jan 2020 | Jul 2020 | Dec 2020 projected | |

| Total state PFML staff | 167 | 307 | 360 |

| Customer care | 98 | 234 | 284 |

| Contractors (mostly IT) | 83 | 54 | |

| Total state + contractors | 250 | 361 | 360 |

Learning 2.1: Key strengths of the PFML program have been public administration with a commitment to customer service, a team-oriented approach, transparency, collaboration with the advisory committee and community partners, and a commitment to continuous improvement.

3. Technology

Washington was able to stand up viable technology systems for on-time implementation for less than originally projected.

ESD released three technology RFPs in October 2017: to configure the internal platform ESD would use for customer administration and accounting; to create the external portal for employers to report data and submit payments and for workers to apply for benefits; and to produce an integration system. Microsoft received the contract to configure the internal system and Deloitte received the other two contracts. Contract teams co-located with PFML program staff.

ESD required its contractors and staff to employ an agile approach for IT systems, so that components were delivered and tested iteratively in small segments rather than one big final product, allowing for continual feedback and improvement. They also employed user stories, to ensure systems would be well designed to serve a diversity of workers, businesses, and circumstances.

The first test came in the fall of 2018 when the system opened to Voluntary Plan (VP) applications. Washington’s policy allows employers to opt out of the state system if they provide benefits at least as good. Employers must submit their plans to ESD for approval, along with a $250 fee – an amount which is insufficient to cover the administrative costs. With payroll premium collections beginning in January 2019, employers interested in VPs needed to have their applications approved prior to January in order to avoid paying premiums. Initially, ESD planned a mid-September launch of the portal, but that deadline slipped to early October. By January 2019, ESD had received 188 complete applications for VPs and approved 119 of them. As of July 2020, 255 employers in Washington are offering VPs.

A larger test came in April 2019, when employers were due to make their first quarterly reports and payments. ESD decided to delay reports from the general population of employers until July and asked selected employers to participate in beta testing the system through April, May and June. These tests caught a few bugs which were fixed. Even this partial influx of premiums was enough to pay back the startup loan due to the state General Fund by the end of June. In July, the full population of employers reported for the first six months of the year. The technology team continued to fix minor bugs and add functionality and convenience features to the system through 2019 and beyond.

As the time for benefits delivery in January 2020 approached, these same tactics of delaying full access to allow for selective testing were not possible. Had the applications portal been ready December 1, the department could have allowed pre-application in order to both test the system and smooth the early approval process. However, the system was not ready until late December.

ESD was able to open the application system to the public on December 30. That went successfully enough that the portal remained open and applications continued to stream in on the New Year holiday, even with the customer care call center closed. The success of the technology launch was tempered by the unanticipated large number of initial applications; the lack of some functionalities, such as being able to edit an application on-line if a situation changed; and long phone wait times and a glitchy phone system that tended to disconnect people after an hour or so of waiting.

Learning 3.1: The agile approach for IT systems has worked well to facilitate continual feedback and improvement.

Learning 3.2: The process would have been improved by requiring the benefits application portal to be ready to receive advance applications one month prior to the benefit availability date. This would have allowed the department to process many of the claims from 2019 events and avoided some of the delays in processing applications that occurred in January and February 2020. Including additional functionalities in the minimal viable products, such as the ability for employers to print out the data they reported and for employees to edit their applications online, would have saved frustration for users.

4. Advisory Committee

The legislation authorizing Washington’s PFML program requires ESD to establish an advisory committee composed of equal numbers of employee- and employer-interest representatives, the PFML program director, and the program ombuds. The Washington State Labor Council and Association of Washington Business nominated the employee- and employer-representatives. The initial group includes people who were part of the 2017 negotiations themselves or whose organization was at the table. The advisory committee has met monthly since October 2017 to provide input on systems development and communications activities. In addition, the advisory committee members all played active roles in the rulemaking process to assure that program rules accurately expressed the agreements reached at the negotiating table.

Learning 4.1: The advisory committee structure and process has facilitated a collaborative approach to implementation and outreach between ESD staff, employers, and communities across the state.

Learning 4.2: At some crucial points, ESD failed to share its assumptions or plans until too late to alter processes or timelines. For example, the advisory committee strongly urged opening applications not later than mid-December, but the technology timeline did not allow that. In addition, ESD did not share or ask for input on its assumptions about initial program take up until after the program was launched and it was clear there was a problem.

5. Rulemaking

As with any major new legislation, the PFML program required considerable rulemaking. Policy staff chose to break rulemaking into multiple phases, focusing attention first on those issues that had to be clarified before premium collection began in January 2019. While the state requires a multi-month process with public notice and opportunities for public engagement, ESD adopted an even longer process with much more opportunity for public engagement for each stage. The strategy was reviewed with and agreed to by the advisory committee.

The rules process raised several issues that required legislative action. Technical amendments bills that were vetted by the advisory committee have passed through the legislature in 2018, 2019, and 2020. These tweaks then required new rulemaking.

Learning 5.1: Completing all the rulemaking sooner in fewer phases would have been better. While the phased approach with extensive time for public engagement allowed issues to be dealt with in the sequence that the program implementation schedule required, this approach also meant that rules for some key program elements were not finalized until 2019. This in turn delayed some systems development. ESD was still able to stand up functioning on-line reporting and application portals successfully, but the initial experience for both employers and employees would have been improved if there had been time to add more features. Stakeholder interest also waned as the process dragged on.

6. Outreach

Research on the first states to add family leave to existing disability insurance programs had documented a general lack of awareness about the family leave portions of those programs. Washington included an outreach requirement in its PFML law and funding in the department budget in an effort to overcome this obstacle to equitable access. Washington’s PFML division hired communications staff and also contracted with a communications consultant.

Early activities were oriented toward general awareness and preparing employers for data and premium collections that would begin in 2019. ESD established a website and social media presence, checked in with California’s department, produced several short videos, FAQs, and a toolkit. All employers received mailings and emails (if the state had their email address) and had the option of joining a listserv to receive updates. From fall of 2018 through April 2019, ESD ran Facebook ads, radio spots in English and Spanish on rural stations, and print ads in business journals featuring business owners. The department also created templates employers could use to communicate with employees about payroll premiums and the PFML program. Over the course of 2018, PFML communications staff gave more than 260 in-person presentations, held webinars with 9,000 participants, and sent out more than 800,000 pieces of mail.

Business associations and Work and Family Coalition members conducted additional outreach to their constituencies. During the 2018 run-up to premium collection that began January 1, 2019, PFML communications staff met with advisory committee members and their communications staff to coordinate and amplify each other’s communications activities.

By summer 2019, the focus of communications efforts shifted to employees. A phone and online survey with 810 participants and 15 focus groups held in Seattle, Yakima, and Spokane helped craft messages for particular groups of workers and messengers, such as small business owners and health care providers. Toward year’s end, ESD released an employee planning guide and toolkits and launched a refreshed website.

ESD initially planned a more aggressive outreach and marketing campaign in the late spring and summer of 2020, after the program was successfully launched. However, the backlog of applications through the spring and the COVID pandemic have delayed that campaign.

Learning 6.1: Having a legislative mandate to conduct outreach and a communications budget to support it is important for a new program that relies on employers to pay premiums and make reports. An additional requirement for multi-lingual outreach and application processes would have been helpful in advancing equitable access to the program. The generally collaborative relationship among advisory committee members and ESD, along with the commitment to a successful program among many business associations that grew out of the 2017 policy negotiations, all contributed to widespread awareness of the program, at least among employers.

7. Launch

The success of ESD and other stakeholders in outreach and education, along with pent up demand for leave benefits, meant three times more applications were received in January and February 2020 than anticipated. This unexpected demand led to wait times of up to 10 weeks for approval and another two weeks to receive benefits. Phone lines were jammed with frustrated workers who desperately needed income.

ESD responded to the unacceptable wait times by authorizing overtime, reassigning staff from lower priority tasks and other parts of the department, streamlining the approval process, adopting a hardship status prioritization process, implementing other efficiencies, contracting out work, and moving to hire more staff. ESD was transparent about the problem, and worked with the advisory committee and media to get the word out – including reassuring people that benefits would be retroactive – and to help manage expectations. The department and Governor’s office also publicly committed to devoting the resources necessary to get wait times down to two weeks by June.

Notably, Washington’s administration did not try to minimize the extent of the problem or the impact of delays on workers and their families. Rather, they accepted responsibility, took immediate steps to address the problem, and committed to delivering workers all the benefits they were entitled to.

Why was ESD’s estimate so far off the mark?

- First of its kind – Washington was the first state to launch a full new program. The four earlier states had long-established disability programs that already were covering the majority of leaves. All of those states added family leave much later and experienced initial usage far below estimates.

- No data from which to estimate pent up demand – While ESD stated in their user guides that people could use leave in 2020 for continuing medical needs from 2019 events or to bond with a child born or placed with the family any time in the previous 12 months, they did not adequately plan for a large initial bow wave of pent up demand. Pioneering states had not seen any such rush when they added family leave to TDI programs, and estimates of ultimate program usage based on national data did not contain such projections.

- Designed for equity – The designers of Washington’s program had studied results from other programs and deliberately included elements to increase usage, especially among lower wage workers, including progressive and relatively high benefits for low- and moderate-wage workers, inclusive family definitions, full portability between jobs, applicability to all sectors, and outreach requirements. Again, there was little basis for projecting how much impact these factors would have.

- Extensive employer outreach – Unlike the first four states that added a small component to an existing program, employers in Washington faced entirely new requirements. The PFML program is housed in the same department as unemployment insurance, but has broader definitions of employee and employer and a separate reporting and application portal. Therefore, ESD and other state departments did extensive outreach to employers throughout 2018 and 2019. Business associations and chambers of commerce across the state facilitated ESD’s outreach and conducted their own as well. As a result, employers – who are often the first place workers turn for information – may well have been better positioned than in other states to inform their employees who needed leave about the new program.

- Resources for employee outreach – While much of ESD’s planned worker outreach is slated for later in 2020 and early 2021, they did some general public education throughout 2018 and 2019. In addition, several advocacy organizations received foundation grants to engage in targeted outreach, and the labor unions and organizations that worked for many years through the Work & Family Coalition for program passage provided information to their members and distribution lists. In contrast, the early states to add family leave to TDI systems had few resources for outreach.

- Different times and higher awareness – The higher public profile of paid family leave in public policy debates in 2020 compared to 2004 through 2014 when the first three states added paid family leave programs, along with more widespread public use of social media networks may have contributed to higher levels of public awareness.

- Failure to check assumptions – Despite the strong and collaborative relationships between ESD, advocates, and business representatives, in this case ESD did not detail their assumptions about initial program use to the advisory committee, and the advisory committee failed to ask probing questions until too late in 2019 to have new staff in place by January.

- Technology not ready for early launch – The advisory committee urged early release of the application portal for testing, training, and early applications, but the system was not ready and fully tested until late December. An earlier launch would have likely alerted ESD to the extent of demand and significantly reduced the delays in receiving payments that Washington workers endured during the first several months of full program operation. However, the complexity of the new system, the short timeframe, and the lengthy rulemaking process all worked against an earlier release.

Learning 7.1: New programs should prepare for higher take-up rates than pioneering programs experienced in their first years, including a one-time initial surge in demand from parents with a birth during the previous year, other events that began prior to benefits launch, and treatments postponed until benefits were available.

The COVID-19 Crisis

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying economic crisis on Washington’s PFML program are not yet clear. Washington was the initial epicenter of the disease in the U.S., with the first identified death on February 29, 2020. Medical and family care applications actually fell in April and May, perhaps as a result of delayed medical treatments and social distancing, then ticked up in June as restrictions on activities in Washington State loosened. The expansions and increased benefits in unemployment insurance (UI) approved by Congress in response to COVID may have diverted some cases to that system.

By the time it became clear that Washington along with the rest of the world was facing a public health and economic crisis, PFML was launched and the state had committed the resources to bring down wait times. Hiring and on-boarding of new staff was already well underway. Moreover, the systems and workplace culture ESD leadership had cultivated from the beginning facilitated a smooth transition to most program staff working from home. While housed in the same department as unemployment insurance, PFML has its own dedicated funding and staff and its own computer system, so was relatively shielded from the onslaught of demand for UI as social distancing and a stay-at-home order took hold.

Longer term, a severe recession and long term job losses, should they develop, would have bigger impacts. Payroll premium collections will be lower than anticipated for much of 2020 at least, and because of layoffs and reduced hours, some workers may not hit the 820 hour per year work requirement needed to maintain eligibility for benefits in 2021. The economic and political fallout from the pandemic could also complicate and slow down program evaluation and improvement.

Notes

Much of the progress of Washington’s PFML program implementation is documented in the minutes and presentations for the Advisory Committee members: https://resources.paidleave.wa.gov/advisory-committee. Appointed members of the Advisory Committee include:

- Employee interest representatives: Joe Kendo, Washington State Labor Council; Maggie Humphreys, MomsRising; Samantha Grad, UFCW Local 21; Marilyn Watkins, Economic Opportunity Institute

- Employer interest representatives: Bob Battles, Association of Washington Business; Christine Brewer, Associated General Contractors of Washington/Avista; Julia Gorton, Washington Hospitality Association; Tammie Hetrick, Northwest Tire Dealers Association

This report has been produced with funding from Family Values @ Work and the Perigee Fund.

[1] For details about Washington’s program, see https://paidleave.wa.gov/

[2] Linda Houser and Thomas P. Vartanian, “Policy Matters: Public Policy, Paid Leave for New Parents, and Economic Security for U.S. Workers,” April 2012, Center for Women and Work, Rutgers, http://cww.rutgers.edu/sites/cww.rutgers.edu/files/documents/working_families/Policy_Matters_Final_4.29.pdf; Maya Rossin-Slater, Christopher J. Ruhm, Jane Waldfogel, “The Effects of California’s Paid Family Leave Program on Mothers’ Leave-Taking and Subsequent Labor Market Outcomes,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 17715, December 2011, http://www.nber.org/papers/w17715; Suma Setty, Curtis Skinner, Renée Wilson-Simmons, “Protecting Workers, Nurturing Families: Building an Inclusive Family Leave Insurance Program: Findings and Recommendations from the New Jersey Parenting Project,” National Center for Children in Poverty, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, Mar 2016, http://www.nccp.org/publications/pub_1152.html.

[3] For preliminary program demographic data, see Advisory Committee presentation, July 2020, https://resources.paidleave.wa.gov/files/Documents/Paid%20Leave%20Advisory%20Committee%20Presentation%20Materials%20July%202020_.pdf. State population data from American Community Survey 2018, Table DP05.

[4] See Watkins, “The Road to Winning Paid Family & Medical Leave in Washington,” Economic Opportunity Institute, Nov 2017, https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/research/post/the-road-to-winning-paid-family-and-medical-leave-in-washington/

[5] See Watkins, “The Road to Winning.”

More To Read

October 14, 2025

Opportunity for many is out of reach

New data shows racial earnings gap worsens in Washington

January 17, 2025

A look into the Department of Revenue’s Wealth Tax Study

A wealth tax can be reasonably and effectively implemented in Washington state

January 6, 2025

Initiative Measure 1 offers proven policies to fix Burien’s flawed minimum wage law

The city's current minimum wage ordinance gives with one hand while taking back with the other — but Initiative Measure 1 would fix that

Kristina Herzman

This was a great collection of data. I appreciate this information.

Sincerely,

Apr 26 2021 at 1:37 PM

Economic Opportunity Institute

So glad you found this research informative, Kristina!

May 3 2021 at 9:54 AM

Rich Clement

Thank you for this data, do you know if any more recent data has been provided from the state of Washington?

Jul 2 2021 at 11:26 AM