Establishing universal paid family and medical leave in the United States is critical to restoring economic security for working families and overcoming the entrenched inequities of race, gender, and class that undermine our economy and squash opportunity for far too many.

Scientific evidence overwhelmingly confirms the importance of paid parental leave to the health and well-being of young children. With our population aging, more workers have responsibilities for caring for older family members and are themselves more at risk of serious illness or injury that may also require a lengthy time away from work.

Currently in the United States, the highest income employees often have generous employer-provided paid leave benefits that allow them to nurture a new child, care for a parent with a health crisis, and fully recover from their own serious health conditions. Middle and lower income workers, on the other hand, have limited or no access to paid leave, forcing them to choose between their family’s health or economic security.

As of 2014, the United States and Papua New Guinea were the only two out of 185 countries and territories in the world that did not guarantee paid maternity leave. Most developed economies also provide paid paternity leave along with guaranteed paid sick leave and vacation time.[1]

Fortunately, programs in California, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island provide highly successful models of family and disability leave programs that other states can replicate. Washington and other states can learn from the experience in these states to craft their own programs in ways that assure that all workers have access, regardless of income or occupation, and that businesses of all sizes can support their workers and communities and continue to thrive.

Adopting statewide paid family and medical leave programs to assure all workers access to paid leave is a crucial step toward overcoming health disparities and inequality in the U.S., and the key to eventual Congressional action to make universal and portable family and medical leave accessible to all U.S. workers.[2]

Documented Benefits of Paid Family and Medical Leave

Boosts infant and parent health

Paid parental leave has lasting positive impacts on the child’s and parents’ physical and emotional health and family economic security. Research documents that a person’s life-long health is substantially determined by the age of two.[3] Adverse effects early in life, including the family stress induced by bouts of economic insecurity and poverty, can have lasting detrimental effects on emotional and physical health, and on social and economic outcomes.

Focusing public policy supports early in life is far less costly and more effective than trying to fix preventable problems later in life. Longer maternity leaves are associated with reduced infant mortality and better infant health.[4] Paid leave allows more parents to stay home for longer periods with their new child, increasing the likelihood the child will receive immunizations and other health care. Mothers are more likely to begin and continue breastfeeding, boosting the child’s immune system, improving cognitive development, and reducing the chances of later allergies, diabetes, and obesity.[5] The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that infants be fed breast milk exclusively for about the first six months of life.[6]

Women also benefit from breastfeeding, by reducing their chance of breast cancer and facilitating a return to pre-pregnancy weight. Longer maternity leaves are also associated with decreased rates of postpartum depression in new mothers. Both parents and children gain from reduced family stress, reduced rates of domestic violence, and strengthened bonding between parents and the child.[7]

Fathers who have the opportunity to fully bond with their infants are more likely to remain involved in their child’s life for the long term, with positive consequences for the child’s mental health and achievement. Men who take longer leaves also continue to spend more time on housework and childcare.[8]

Impacts on children are long lasting. A Canadian study found that children who as infants had at least one parent taking parental leave scored higher on measures of physical health, social competence, and communication when they reached kindergarten than those whose parents had not taken leave. The highest scores were for children with a parent who had taken between six and twelve months of leave.[9]

Promotes family economic security and equity

Family economic outcomes are better when new parents receive paid leaves. Women with paid maternity leave are more likely to return to work in the year following a birth and to have higher wages over time. Use of TANF and SNAP or food stamps by both new mothers and fathers also drop when they have paid leave.[10] Studies have also found positive associations with men taking longer paternity leaves and their partners’ workforce attachment.[11] Stronger family finances boost a child’s chances long term, increasing the likelihood that they will do well in school and opening doors of opportunity.

Protects workers’ health

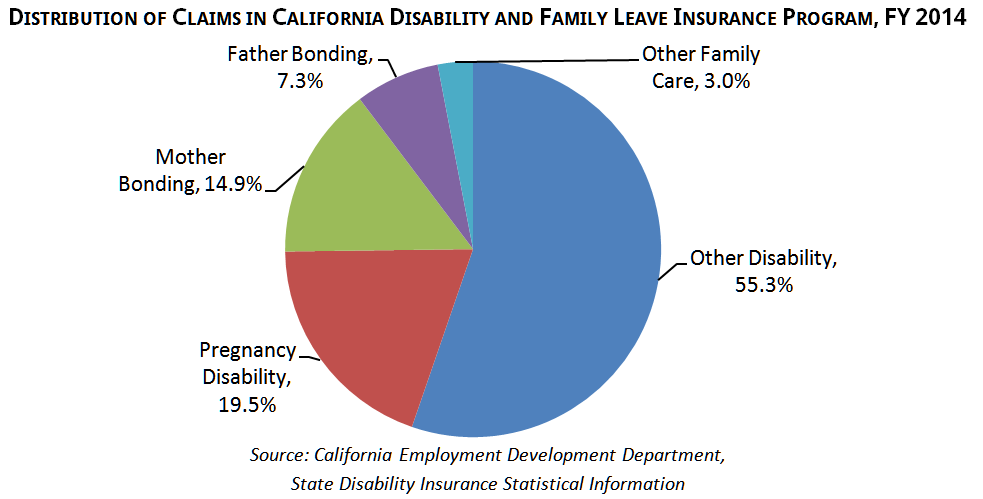

Paid medical leave helps cushion the economic impact when people have an accident that causes serious injury or encounter a serious health condition (at any age) that interferes with their ability to work. An aging workforce puts more people at risk of developing cancer, heart disease, and other conditions. The majority of claims in both California’s and New Jersey’s family leave and temporary disability insurance systems are for the worker’s own health.[12]

Supports elder and family care

Paid family leaves also support working adults who have care responsibilities for spouses, siblings, grandparents, and other family members, along with parents. A recent study by the AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving found that 43.5 million adults in the U.S. (18.3%) provide unpaid care for another person, including 14% who care for someone over age 50. About half are caring for a parent or parent-in-law, and 35% for another family member. The majority of unpaid caregivers are women, and six in ten are also employed.[13]

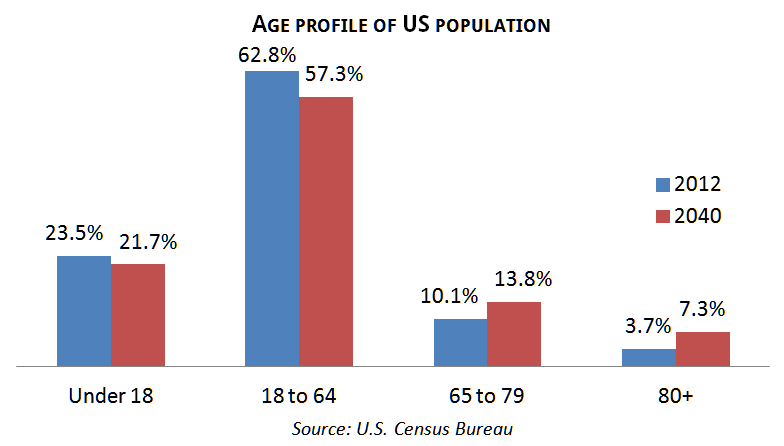

Providing elder care while holding a job and sometimes also having young children at home can be stressful, cause health problems for the caregiver, and result in lost income and career opportunities.[14] In the Caregiving survey, 22% reported that caregiving caused their health to get worse and 61% that it had impacted their jobs.[15] The Census Bureau projects that the percentage of people over age 80 in the U.S. will double over the next 25 years.[16]

Lack of Access Promotes Inequality

Currently, the benefits associated with lengthy paid parental leaves in the U.S. are available mostly to babies lucky enough to be born in one of the handful of states with a disability insurance/family leave program, or whose parents are highly paid professionals with especially generous employers. Extended time off work with pay to go through treatment and fully recover from serious illness or injury, or care for a family member, is also not available to most workers.

In 2015, only 12% of U.S. private sector workers had a paid family leave benefit. Some workers are able to cobble together employer-provided sick leave, vacation, and/or temporary disability insurance during FMLA-covered leaves (see p. 5). But 39% of private sector workers get no paid sick leave and 24% no vacation. Access is highly skewed by income – people with the highest 10% of wages are nearly four times more likely than those in the bottom 10% to have sick leave, and more than eight times more likely to have paid family leave.[17]

The growing paid sick days movement has significantly expanded access to sick leave in about 30 cities and 5 states (as of this writing). But even workers with paid leave have a hard time saving up enough for adequate parental leave or to cope with health crises such as a cancer diagnosis or serious accident. U.S. private sector workers with paid sick leave typically only accrue six days per year, even after five years on the job.[18] Those with vacation typically get ten days after one year and 15 after five years in larger companies, but fewer days in firms with fewer than 100 employees.[19]

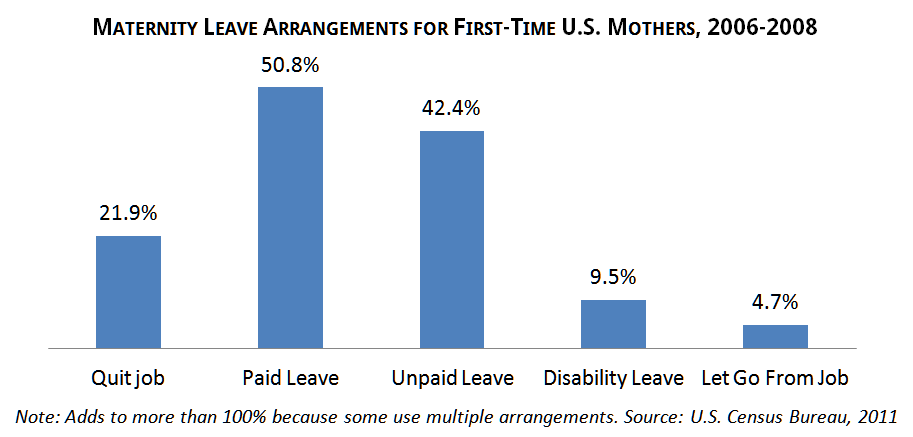

A U.S. Census Bureau analysis of maternity leave arrangements for first-time mothers found that while just over half of U.S. women who worked during pregnancy received some pay during maternity leave, only about one-fourth were paid for their entire leave. More than a quarter of women either quit or were let go from their jobs. Women with a B.A. degree or higher were more than twice as likely as women with only a high school education to receive paid maternity leaves (66.3% to 31.6%), and white women were slightly more likely than women of color.[20]

Despite the recommendation of health professionals to exclusively breastfeed for six months, and the high cost of infant childcare, the Census Bureau found 59% of women were back at work within three months of childbirth.[21] An analysis conducted for In These Times found one in four U.S. women return to work within two weeks of giving birth.[22]

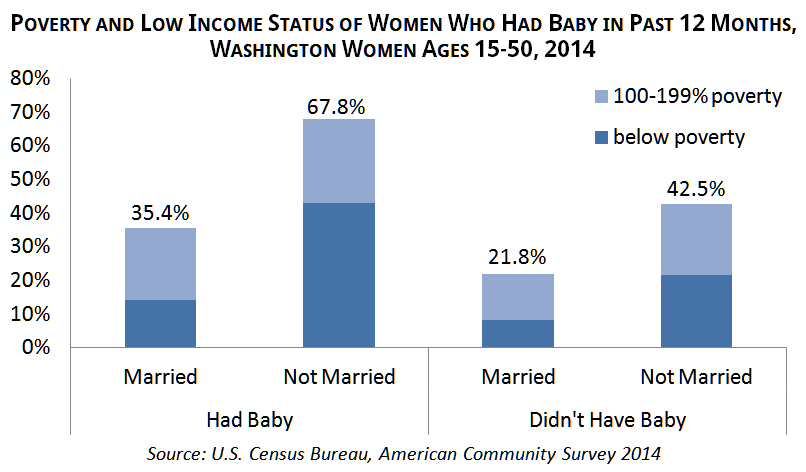

Lack of paid parental leave seriously undermines family economic security. Women who have had a baby in the past twelve months are considerably more likely to be poor or low income than those who have not had a baby. In Washington, more than one in three married women and two-thirds of unmarried women who gave birth in the past year have incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level. Altogether 19.3% of Washington children under the age of 5 live in poverty.[23]

Poverty has profound lasting negative effects on young children’s emotional and physical health, including interfering with brain growth and development.[24] But experience with the Earned Income Tax Credit and other programs demonstrate that policy changes which raise family incomes can result in meaningful improvements in child development.[25]

Policy Successes and the Path Forward

Federal Family and Medical Leave Act

Since 1993, the federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) has guaranteed up to twelve weeks job-protected leave for workers with: a serious health condition; a newborn or newly placed adopted or foster child; or a seriously ill child, spouse, or parent.[26] Millions of people have benefitted. However, the FMLA has major gaps: employers are not required to provide pay, only employers with 50 or more employees must comply, and workers are only eligible if they have been with their current employer at least a full year and worked at least 1,250 hours in the past year. With these restrictions, more than four in ten workers are not covered. Many who in theory have access to leave cannot afford to take it without pay.[27]

State Disability and Family Leave Insurance Programs

Several states have established programs to assure workers receive wage replacement during prolonged leaves to care for a new child or serious health concern. In the 1940s, Rhode Island, California, New Jersey, and New York approved temporary disability insurance (TDI) programs that covered most workers. Hawaii followed in 1969.[28]

Originally, these plans excluded pregnancy and childbirth-related disabilities, but that changed with passage of the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978. Since then, women in these states with healthy pregnancies and normal deliveries have typically been able to collect disability benefits starting two weeks prior to their due date until six weeks after childbirth, with longer leaves allowed when medically necessary.

In 2002, California became the first state to add family leave to the system. Both parents can take six weeks of bonding leave for a newborn or newly adopted child – for the birth mother, in addition to her disability leave. Leave is also available to care for family members with serious health conditions. New Jersey approved a similar benefit in 2008 and Rhode Island in 2013.[29] New York’s Assembly passed twelve weeks of family leave in 2016.[30]

Each system varies somewhat in design. California covers up to 52 weeks of disability leave and the other four states cover up to 26 weeks. New Jersey’s program provides two-thirds of usual pay. California provided 55% of wages for many years, but legislation passed in 2016 that will increase benefits beginning in 2018 to 70% for workers with incomes below $20,000 and 60% for those with higher incomes.[31] New York’s 2016 law also boosted previous benefit levels for the new family leave program.

In California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island, the program is primarily operated as social insurance, with the state holding funds in trust and paying benefits, while New York and Hawaii require employers to provide benefits that meet state standards, either on their own or through private insurance. Payroll premiums in California and Rhode Island are paid by employees, but employers are required to contribute at least a portion in New York, New Jersey, and Hawaii.[32]

During the 1980s, Washington legislators passed pioneering family leave policy that helped pave the way for Congressional action on the FMLA. The “chicken pox law”, passed in 1988, assured that workers with paid sick leave could use it to care for a sick child. The following year, House Bill 1581 provided job-protected, unpaid leave to parents to care for a newborn, newly adopted, or terminally ill child.[33]

Following passage of the federal FMLA, advocates and policymakers across the country continued pushing for universal paid family leave. With the encouragement of the Clinton administration, Washington and a number of other states introduced “Baby UI” bills during the late 1990s that would have extended unemployment insurance to new parents. Those bills faced staunch opposition from business lobbying groups, and none passed. Early in the Bush administration, the U.S. Department of Labor changed federal rules to shut down that possibility.

The Washington Family Leave Coalition – women’s, labor, senior, faith, and other community groups coordinated by the Economic Opportunity Institute – formulated a new plan for family and medical leave insurance modeled on the state TDI programs. That proposal was first introduced in Washington’s legislature in 2001.[34]

The recession that hit later that year was particularly severe in the Pacific Northwest, triggering state budget cuts in 2002 and 2003. Faced with a climate of austerity that made passage of a new program unlikely, the coalition put paid family leave on hold and crafted the Family Care Act for introduction in the 2002 legislature. The bill expanded the 1988 “chicken pox” law to allow workers to use any employer-provided paid leave to care for ill spouses, parents, parents-in-law, and grandparents, as well as sick children. The 2002 bill passed unanimously in the House and with only four no votes in the Senate.[35]

Knowing the Family Care Act would not help workers whose employers did not already offer paid leave, the following year the coalition and policymakers developed and introduced a bill to establish a minimum standard of employer-provided paid leave for all workers, helping launch the paid sick days movement.[36]

In 2005, legislative champions Senator Karen Keiser and Representative Mary Lou Dickerson reintroduced family and medical leave insurance with coalition backing. Under the strong leadership of Senate Majority Leader Lisa Brown of Spokane, that bill passed the Senate with bipartisan support, but stalled in the House.[37]

Conditions finally seemed ripe to pass family and medical leave insurance in 2007. The economy was strong and Democrats, who generally favored the concept, had majorities in both chambers along with the Governor’s seat. The reintroduced paid family leave law again sailed through the Senate with bipartisan support, including funding for benefits from payroll premiums. However, in the face of strong opposition from corporate lobbyists, the House balked. It passed a stripped down bill that covered only parental leave – and provided no funding.[38]

The coalition continued to encourage legislators to expand the 2007 law to a full program that would cover both family and disability leave with dedicated funding. In 2008, the state legislature approved a General Fund appropriation for start-up activities, in anticipation of a bill for a permanent funding in 2009 that would allow the program to start that fall. But the Great Recession, which began in late 2008, devastated Washington’s budget for several years, making expansion and funding of family leave politically unfeasible. Instead, the Legislature postponed implementation indefinitely.

The (now renamed) Washington Work and Family Coalition turned attention back to the issue of sick leave. Over the next several years, the Coalition helped seed and support local coalitions which won paid sick days victories in Seattle (2011),[39] Tacoma (2015),[40] and Spokane (2016).[41] Statewide paid sick and safe leave bills passed the Washington House in 2014 and 2015, but died in the Republican-controlled Senate.[42]

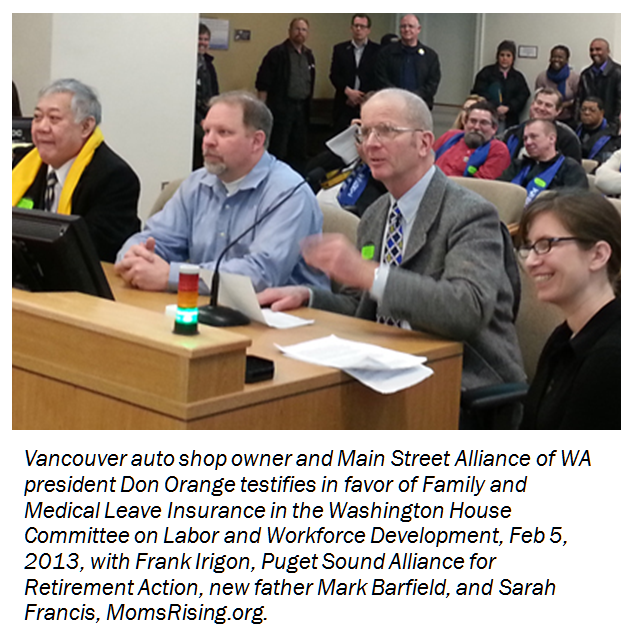

Leading up to the 2013 legislative session, the coalition updated and expanded its family and medical leave insurance proposal to cover twelve weeks of family leave to care for a new child or seriously ill family member and up to twelve weeks of disability leave. Workers on leave would receive two-thirds of their usual pay up to $1,000 per week, funded through payroll premiums of 0.4% split equally between employees and employers, with the typical worker paying less than $2.00 per week.

Leading up to the 2013 legislative session, the coalition updated and expanded its family and medical leave insurance proposal to cover twelve weeks of family leave to care for a new child or seriously ill family member and up to twelve weeks of disability leave. Workers on leave would receive two-thirds of their usual pay up to $1,000 per week, funded through payroll premiums of 0.4% split equally between employees and employers, with the typical worker paying less than $2.00 per week.

Bills were introduced in both 2013 and 2015 and passed the House Labor Committee in both years .[43] Despite support from many small business owners, paid family leave bills have been opposed by corporate lobby groups, including the Association of Washington Business, Washington Food Industry Association, and Independent Business Association, and as a result faced a hostile political climate in the state Senate, which has been controlled by Republicans since 2013.[44]

Action Around the Country

The need for policy change on paid leave is increasingly in the national spotlight. Nearly 30 cities and five states have now passed paid sick days laws with high levels of public support.[45]

Over the past two years, a growing number of both private and public employers have announced new or expanded paid parental leave offerings for their own employees, including Amazon, Microsoft, and other tech giants,[46] and both the City of Seattle and King County, Washington.[47] In the same week in April 2016, California raised benefits for its state family leave and TDI program, and New York adopted statewide paid family leave. [48] Legislators in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and the District of Columbia are considering establishing entirely new family and disability leave insurance programs in 2016.

Polling shows both paid sick days and paid family and medical leave insurance are wildly popular with voters.[49] Two recent polls in Connecticut by AARP and Connecticut Working Families found 83% and 75% of voters, respectively, supported establishing a family and medical leave insurance program.[50] President Obama and Secretary of Labor Perez have urged more cities and states to act and Democratic presidential candidates have announced support for federal passage of both paid sick days and paid family and medical leave.

Despite all this activity, the U.S. remains a long way from universal paid family leave. While many individual business owners support paid leave legislation, most business lobby associations at the local, state, and federal levels oppose new labor standards and and actively campaign against them.[51] The path to eventual Congressional victory will be long and will require additional states to adopt programs and provide even more proof that family-friendly policies are fully compatible with a strong economy and strong businesses.

Proven Results in TDI/Paid Family Leave States

Positive Outcomes for Workers

Recent studies have found that women in states with disability or family leave insurance were twice as likely to take paid leave after having a baby than women in other states. They also took leaves that were on average 22 days longer. Among women with incomes below 200% of the poverty level, use of paid leave tripled in states with disability or family leave insurance. After family leave was added to disability insurance in California in 2004, average maternity leaves increased from 1 week to 7 weeks for African American mothers, and from 4 to 7 weeks for white mothers. Fathers were more than twice as likely to take leave for a new child.[52]

A qualitative study of low-income parents in New Jersey found that those who used the state family leave insurance program were much more likely to return to their jobs than those who did not. Mothers who used the program were much more likely to be working at the time of the study, and on average breastfed for one month longer, than those who did not use paid family leave.[53]

The five states with established universal TDI systems – California, Hawaii, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island – together are home to 21% of all jobs in the United States.[54] These states’ economies have grown, evolved, and diversified over time along with the rest of the country. Over the past 14 years, all but Hawaii have acted to establish universal paid family leave alongside disability insurance. California has expanded its original family leave program twice more, adding siblings, grandparents and other family members to those covered, and increasing benefit levels for both family and disability leave.

For employers, these universal social insurance programs have the advantages of minimal administration and low and predictable premium costs. Workers notify employers about their leaves, but the state, or in some cases a third party, is responsible for verifying that a claim is valid and administering benefits.[55] Employers do not have to pay workers while on leave, so can use those funds to pay replacement workers – although some employers voluntarily coordinate employer-provided paid leave benefits so that workers receive full pay.[56]

In addition to the social and health benefits of workers having access to family and medical leave benefits, businesses can benefit from lower turnover, higher morale and productivity, and reduced health care spending. Greater family economic security also translates into more discretionary income and consumer spending. Women with paid maternity leave are less likely to quit their jobs following childbirth and to earn more over time,[57] and cities and states that have adopted paid sick leave standards have maintained strong and competitive economies.[58]

The majority of employers themselves have consistently reported no or little impact from public policy changes that promote family-friendly workplaces. A major 2012 U.S. Department of Labor survey on FMLA and leave-taking behavior found that 37% of FMLA-covered worksites reported positive impacts on employee turnover, absenteeism, productivity, morale, or business profitability, while only 8% reported negative impacts. Fewer than 2% of employers reported misuse of FMLA.[59]

Several years following implementation of California’s paid family leave program, a survey of a random sample of firms found that for the vast majority, the program had no or minimal impact. Only 13% reported increased costs, primarily from hiring replacement workers for people on leave, while 9% reported reduced costs from lower turnover.[60] In-depth interviews with 18 New Jersey firm managers who had had at least one employee take advantage of that state’s paid family leave program similarly found that the majority perceived no impact on their operations. Two reported increased profitability as a result, while two others reported decreased profitability. The most commonly cited impact was in paperwork, with two of 18 reporting increases and an additional six noting minimal increases.[61]

Just before and one year after implementing paid family leave, a survey comparing small (10-100 employees) firms in Rhode Island to similar companies in neighboring Connecticut and Massachusetts (which did not implement programs), found no evidence of significant impact – either positive or negative – from the program. Moreover, 61% of Rhode Island firms surveyed supported the program, with only 24% opposed.[62]

Lessons for New State Programs

Business Education and Outreach

Multiple studies have documented that over time, businesses have adapted to the FMLA, new paid family leave programs, and new paid sick days standards and have little trouble implementing policies. Nevertheless, there can be initial confusion and some hassle in adjusting existing policies and practices to new standards.

The Employers Association of New Jersey (EANJ), which describes itself as “advancing the principles of individual freedom in labor relations,”[63] conducted a number of seminars around their state for small businesses following adoption of New Jersey’s paid family leave program in 2008. EANJ reported that misinformation spread by opponents of the policy during attempts to defeat it legislatively, and a lack of clear and consistent information from the state, had left many business owners confused about how the program was structured, what their role was, and whether their employees were covered by the policy.[64]

A University of Washington study of the impacts of Seattle’s paid sick and safe leave ordinance found that some businesses experienced initial confusion about requirements and hassle in adjusting their internal systems, but after the first few months, had made the adjustments and found the overall impact less than they anticipated.[65] That initial confusion was true even though the City mailed information to all licensed businesses, conducted workshops in neighborhood business districts across the city prior to implementation, posted extensive information on its website, and offered one-on-one technical assistance. But the UW study also found that many businesses that thought they were in full compliance actually were not, and that many workers had no knowledge of their rights to sick leave.

Worker Education and Outreach

Lack of knowledge about paid leave programs and policies has been a common theme, especially among the most vulnerable workers. A 2014 statewide poll in California, ten years after that state implemented paid family leave, found that only 36% of state voters were aware of the program. Low income and Hispanic voters were least likely to know about it.[66]

Studies in New Jersey have also shown a lack of knowledge about that state’s paid family leave program. One concluded that neither the state nor employers were doing enough to get the word out to employees.[67] A poll of New Jersey residents three years after paid family leave was implemented there found six in ten residents had not heard about the program.[68] A qualitative study of low-income parents in New Jersey also found that many had not used the program simply because they were unaware of it. Others felt intimidated to approach their employers or assumed they were not eligible because their employers did not provide them with information about it.[69]

The New Jersey study of low-income parents found that among those who had used the paid family leave program, some found the application process difficult or experienced delays in getting benefits. Many women expressed a desire for longer than the six weeks of leave afforded by New Jersey’s program. Especially among men, lack of job security for those not covered by FMLA and not receiving full wage replacement were additional barriers to use.[70]

Maximizing Positive Outcomes

Experience from existing state programs suggests that policy details and implementation strategies can be crafted to maximize the positive impacts of family and medical leave insurance on health and family economic security.

Policy considerations include:

- Leaves need to be long enough to meet common basic health needs of workers, infants, and family members.

- Wage replacement rates need to be structured so that low- and moderate-income workers can afford to take time off, along with higher income.

- Providing job security to workers beyond FMLA will also enhance the ability of economically vulnerable workers to take leaves.

Implementation considerations:

- Educational materials to employers must be clear and provided through a variety of methods. Employers need to understand what they must do to comply, with minimal confusion and paperwork. Most workers will find out about the program through their employers, so employers must know when an employee is likely to be eligible for benefits and where to direct the employee to apply.

- Outreach to workers must also be multipronged and continuous, including through health providers and community organizations, particularly those who serve lower income and other vulnerable workers who are least likely to otherwise know about benefits available to them.

- The application process must be simple, with help available in multiple languages and culturally appropriate ways.

Conclusion

The evidence is consistent and compelling: establishing family and medical leave insurance for all workers will reduce health disparities, dramatically improve outcomes for young children, enhance the quality of life of seniors, boost the lifetime earnings of women, and reduce the high social and public costs associated with poverty and inequality in the United States. We have proven policy tools to enact universal, portable, low cost systems at the state and federal levels now. Voters of all parties support adoption of these policies. It is time for Washington and other states to move forward.

Notes

[1] International Labour Organization, “Maternity and Paternity at Work: Law and practice across the world,” 2014, http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_242617.pdf.

[2] An analysis by the Washington State Board of Health of the family and medical leave insurance program proposed to the legislature in 2015 found strong evidence that its adoption would decrease health disparities for low income workers and families of color. Washington State Board of Health, “Health Impact Review of SB5459: Implementing Family and Medical leave Insurance,” Aug 31, 2015, http://sboh.wa.gov/Portals/7/Doc/HealthImpactReviews/HIR-2015-10-SB5459_092815.pdf.

[3] Stephen Bezruchka, “Early Life or Early Death,” International Journal of Child, Youth, and Family Studies, 2015 (2), https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/ijcyfs/article/view/13499.

[4] Jody Heymann, Amy Raub, Alison Earle, “Creating and Using New Data Sources to Analyze the Relationship Between Social Policy and Global Health: The Case of Maternal Leave,” Public Health Rep. 2011; 126(Suppl 3): 127–134, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3150137/; McGill University. “Longer maternity leave linked to better infant health: Study of low- and middle-income countries shows paid maternity leave policies could help prevent infant deaths.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 30 March 2016. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/03/160330123502.htm.

[5] Washington State Board of Health, “Health Impact Review of SB5459: Implementing Family and Medical leave Insurance,” Aug 31, 2015, http://sboh.wa.gov/Portals/7/Doc/HealthImpactReviews/HIR-2015-10-SB5459_092815.pdf.

[6] American Academy of Pediatrics, Breastfeeding Initiative, FAQs webpage viewed Apr 19, 2016, https://www2.aap.org/breastfeeding/faqsBreastfeeding.html.

[7] Washington State Board of Health, “Health Impact Review of SB5459: Implementing Family and Medical leave Insurance,” Aug 31, 2015, http://sboh.wa.gov/Portals/7/Doc/HealthImpactReviews/HIR-2015-10-SB5459_092815.pdf.

[8] U.S. Department of Labor, “Paternity Leave: Why Parental Leave for Fathers Is So Important to Working Families,” Jun 17, 2015, viewed Apr 25, 2016, http://www.dol.gov/asp/policy-development/PaternityBrief.pdf.

[9] Anca Gaston, Sarah A. Edwards, and Jo Ann Tober, “Parental leave and child care arrangements during the first 12 months of life are associated with children’s development five years later,” International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies (2015) 6(2): 230–251, https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/ijcyfs/article/view/13500.

[10] Linda Houser and Thomas P. Vartanian, “Pay Matters: The Positive Economic Impacts of Paid Family Leave for Families, Businesses and the Public,” Center for Women and Work at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, 2012, http://cww.rutgers.edu/sites/cww.rutgers.edu/files/documents/working_families/CWW_Paid_Leave_Brief_Jan_2012_0.pdf.; Maya Rossin-Slater, Christopher J. Ruhm, Jane Waldfogel, “The Effects of California’s Paid Family Leave Program on Mothers’ Leave-Taking and Subsequent Labor Market Outcomes,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 17715, December 2011, http://www.nber.org/papers/w17715.

[11] U.S. Department of Labor, “Paternity Leave: Why Parental Leave for Fathers Is So Important to Working Families,” Jun 17, 2015, viewed Apr 25, 2016, http://www.dol.gov/asp/policy-development/PaternityBrief.pdf.

[12] California Employment Development Department, State Disability Insurance Statistical Information, http://www.edd.ca.gov/Disability/pdf/qsdi_DI_Program_Statistics.pdf, and http://www.edd.ca.gov/Disability/pdf/qspfl_PFL_Program_Statistics.pdf; New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, Temporary Disability Insurance Annual Report 2014, http://lwd.dol.state.nj.us/labor/forms_pdfs/tdi/TDI%20Report%20for%202014.pdf; and Family Leave Insurance Annual Report 2014, http://lwd.dol.state.nj.us/labor/forms_pdfs/tdi/FLI%20Summary%20Report%20for%202014.pdf.

[13] AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving, “Caregiving in the U.S. 2015”, http://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/2015_CaregivingintheUS_Executive-Summary-June-4_WEB.pdf.

[14] New York Times, “Elder caregivers often sacrifice their careers,” Dec. 8, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/08/health/elder-caregivers-often-sacrifice-their-careers.html?_r=0.

[15] AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving, “Caregiving in the U.S. 2015”, http://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/2015_CaregivingintheUS_Executive-Summary-June-4_WEB.pdf.

[16] US. Census Bureau, “An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States,” May 2014, https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf.

[17] US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Table 32. Leave benefits: Access, private industry workers, National Compensation Survey, March 2015, http://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2015/ownership/private/table32a.pdf.

[18] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Compensation Survey 2015, Table 35, http://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2015/ownership/private/table35a.pdf.

[19] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Compensation Survey 2015, Table 38, http://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2015/ownership/private/table38a.pdf.

[20] U.S. Census Bureau, “Maternity Leave and Employment Patterns of First-Time Mothers: 1961–2008,” Oct 2011, https://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/p70-128.pdf.

[21] Elise Gould and Tanyell Cooke, “High quality child care is out of reach for working families,“ Oct 2015, http://www.epi.org/publication/child-care-affordability/; Child Care Aware, “What Is the Cost of Child Care in Your State? 2015,” webpage viewed May 3, 2016, http://usa.childcareaware.org/advocacy-public-policy/resources/reports-and-research/costofcare/; U.S. Census Bureau, “Maternity Leave and Employment Patterns of First-Time Mothers: 1961–2008,” Oct 2011, https://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/p70-128.pdf.

[22] In These Times, “The Real War on Families, Aug 18, 2015, http://inthesetimes.com/article/18151/the-real-war-on-families.

[23] EOI analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey data, 2014.

[24]Elizabeth Sowell, et al, “Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents,” Nature Neuroscience 18, 773–778 (2015) published online Mrch 30, 2015, http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/v18/n5/full/nn.3983.html;

[25] Rita Hamad and David Rehkopf, “Poverty and Child Development: A Longitudinal Study of the Impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit,” American Journal of Epidemiology, published online Apr 7, 2016, http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2016/04/06/aje.kwv317.abstract.

[26] US Department of Labor, FMLA, viewed Apr 13, 2016, http://www.dol.gov/general/topic/benefits-leave/fmla.

[27] Barbara Gault, Heidi Hartmann, Ariane Hegewisch, Jessica Milli, Lindsey Reichlin, Paid Parental Leave in the United States: What the Data Tell Us about Access, Usage, and Economic and Health Benefits, Institute for Women’s Policy Research, (January 2014), http://iwpr.org/initiatives/family-and-medical-leave.

[28] U.S. Social Security Administration, Annual Statistical Supplement, 2012, “Temporary Disability Insurance Program Description and Legislative History,” https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2012/tempdisability.html.

[29] Ellen Bravo, “Rhode Island becomes the third state with paid family leave,” July 3, 2013, Family Values @ Work, viewed April 14, 2016, http://familyvaluesatwork.org/blog/family-values-at-work/rhode-island-poised-to-be-third-state-with-paid-family-leave.

[30] Carl Heastie, Press Release: “SFY 2016-17 Enacted Budget Raises the Minimum Wage and Delivers Paid Family Leave to Support Workers and their Families,” Apr 1, 2016, viewed Apr 14, 2016, http://assembly.state.ny.us/Press/20160401c/.

[31] Los Angeles Times, “Brown signs California law boosting paid family leave benefits,” April 11,2016, http://www.latimes.com/politics/la-pol-sac-paid-family-leave-california-20160411-story.html.

[32] Information on the state programs can be found: California Employment Development Department, http://www.edd.ca.gov/Disability/FAQs.htm; Hawaii Disability Compensation Division, http://labor.hawaii.gov/dcd/home/about-tdi/; New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, http://lwd.dol.state.nj.us/labor/tdi/tdiindex.html, http://lwd.dol.state.nj.us/labor/fli/fliindex.html; New York Workers Compensation Board, http://www.wcb.ny.gov/content/main/offthejob/IntroToLaw_DB.jsp; Rhode Island Department of Labor and Training, http://www.dlt.ri.gov/tdi/tdifaqs.htm.

[33] Washington Legislature, ESHB 1319, 1988 and 1581, 1989, http://app.leg.wa.gov/dlr/home/.

[34] Washington Legislature, House Bill 1520 and Senate Bill 5420, 2001, http://app.leg.wa.gov/dlr/billsummary/default.aspx?bill=5420&year=2001, http://app.leg.wa.gov/dlr/billsummary/default.aspx?bill=1520&year=2001.

[35] Washington Legislature, Senate Bill 6426 (House Bill 2364) 2002, http://app.leg.wa.gov/dlr/billsummary/default.aspx?bill=6426&year=2001, http://app.leg.wa.gov/dlr/billsummary/default.aspx?bill=2364&year=2001.

[36] Washington Legislature, House Bill 1221 (Dickerson), Senate Bill 5377 (Keiser), http://app.leg.wa.gov/dlr/billsummary/default.aspx?bill=1221&year=2003, http://app.leg.wa.gov/dlr/billsummary/default.aspx?bill=5377&year=2003.

[37] Washington Legislature, Senate Bill 5069 and House Bill 1173, 2005, http://app.leg.wa.gov/dlr/billsummary/default.aspx?bill=5069&year=2005.

[38] Washington Legislature, Senate Bill 5659, 2007, http://app.leg.wa.gov/dlr/billsummary/default.aspx?bill=5659&year=2007.

[39] Marilyn P. Watkins, “Lessons from Winning Paid Sick Days in Seattle,” 2012, Seattle Coalition for a Healthy Workforce and Economic Opportunity Institute, http://www.eoionline.org/work-family/paid-sick-days/lessons-from-winning-paid-sick-days-in-seattle/.

[40] Healthy Tacoma, https://healthytacoma.net/.

[41] Spokane Alliance, Accomplishments, viewed Apr 18, 2016, http://iafnw.org/spokanealliance/Accomplishments.

[42] Washington Legislature, House Bill 1356 and Senate Bill 5306, 2015, http://app.leg.wa.gov/dlr/billsummary/default.aspx?bill=1356&year=2015.

[43] Washington Legislature, House Bill 1273 and Senate Bill 5459, 2015, http://app.leg.wa.gov/dlr/billsummary/default.aspx?bill=1273&year=2015.

[44] House Bill Report 1457 (2013), http://lawfilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2013-14/Pdf/Bill%20Reports/House/1457%20HBR%20LWD%2013.pdf. House Bill Report HB 1273 (2015), http://lawfilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2015-16/Pdf/Bill%20Reports/House/1273%20HBR%20LAB%2015.pdf.

[45] Family Values @ Work, Timeline of Wins, viewed Apr 15, 2016, http://familyvaluesatwork.org/media-center/paid-sick-days-wins.

[46] CNN Money, “Microsoft bumps up its parental leave benefits, Aug 6, 2015, http://money.cnn.com/2015/08/05/technology/microsoft-maternity-leave/; Wired, “Tech’s selfish reasons for offering parental leave,” Aug 13, 2015, http://www.wired.com/2015/08/techs-selfish-reasons-offering-parental-leave/; TechCrunch, “Amazon revamps parental leave policy,” Nov 2, 2015, http://techcrunch.com/2015/11/02/amazon-revamps-parental-leave-policy/.

[47] The Stranger, “Seattle City Council approves paid parental leave for all city employees,: Apr 13, 2015, https://www.thestranger.com/blogs/slog/2015/04/13/22045769/seattle-city-council-approves-paid-parental-leave-for-all-city-employees; Seattle Times, “King County oks paid parental leave for some employees,” Dec 8, 2015, http://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/politics/king-county-oks-paid-parental-leave-for-some-employees/.

[48] The Intelligencer, Associated Press, “California Governor OKs increased pay during family leave,” Apr 12, 2016, http://www.theintelligencer.net/page/content.detail/id/1139055/California-governor-OKs-increased-pay-during-family-leave.html?isap=1&nav=537.

[49] National Partnership for Women and Families, Press release, “Poll: Significant Support for Economic Policies for Working Families,” Feb 2014, http://www.nationalpartnership.org/news-room/press-releases/poll-significant-support-for-economic-policies-for-working-families.html?referrer=https://www.google.com/.

[50] New Haven Register, “AARP poll strong support for Connecticut to adopt paid family leave law,“ Apr 14, 2016, http://www.nhregister.com/general-news/20160414/aarp-polls-strong-support-for-connecticut-to-adopt-paid-family-leave-law.

[51] See, for example, Eileen Appelbaum and Ruth Milkman, “Paid Family Leave Pays Off in California, Jan 29, 2011, Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2011/01/paid-family-leave-pays-off-in.html; Washington House Bill Report 1457 (2013), http://lawfilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2013-14/Pdf/Bill%20Reports/House/1457%20HBR%20LWD%2013.pdf

[52] Linda Houser and Thomas P. Vartanian, “Policy Matters: Public Policy, Paid Leave for New Parents, and Economic Security for U.S. Workers,” April 2012, Center for Women and Work, Rutgers, http://cww.rutgers.edu/sites/cww.rutgers.edu/files/documents/working_families/Policy_Matters_Final_4.29.pdf; Maya Rossin-Slater, Christopher J. Ruhm, Jane Waldfogel, “The Effects of California’s Paid Family Leave Program on Mothers’ Leave-Taking and Subsequent Labor Market Outcomes,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 17715, December 2011, http://www.nber.org/papers/w17715.

[53] Suma Setty, Curtis Skinner, Renée Wilson-Simmons, “Protecting Workers, Nurturing Families: Building an Inclusive Family Leave Insurance Program: Findings and Recommendations from the New Jersey Parenting Project,” National Center for Children in Poverty, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, Mar 2016, http://www.nccp.org/publications/pub_1152.html.

[54] EOI calculation from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics March 2016 data for nonfarm employment, seasonally adjusted.

[55] Rhode Island’s program is entirely through the state system. California and New Jersey allow employers to self- or privately insure in certain circumstances, but the majority of employers are in the state system. New York and Hawaii programs are largely privatized.

[56] 60% of employers reported coordinating benefits in a survey of California employers. Eileen Appelbaum and Ruth Milkman, “Paid Family Leave Pays Off in California, Jan 29, 2011, Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2011/01/paid-family-leave-pays-off-in.html.

[57] Linda Houser and Thomas P. Vartanian, “Pay Matters: The Positive Economic Impacts of Paid Family Leave for Families, Businesses and the Public,” Center for Women and Work at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, 2012, http://cww.rutgers.edu/sites/cww.rutgers.edu/files/documents/working_families/CWW_Paid_Leave_Brief_Jan_2012_0.pdf.; Maya Rossin-Slater, Christopher J. Ruhm, Jane Waldfogel, “The Effects of California’s Paid Family Leave Program on Mothers’ Leave-Taking and Subsequent Labor Market Outcomes,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 17715, December 2011, http://www.nber.org/papers/w17715.

[58] Marilyn P. Watkins, “Local Results of Paid Sick Days Laws, Economic Opportunity Institute, Jan 2016, http://www.eoionline.org/work-family/paid-sick-days/local-results-of-paid-sick-days-laws/.

[59] Abt Associates, Inc., Family and Medical Leave in 2012: Final Report, pp. 155-157, U.S. Department of Labor, http://www.dol.gov/asp/evaluation/fmla/FMLA-2012-Technical-Report.pdf.

[60] Eileen Appelbaum and Ruth Milkman, “Paid Family Leave Pays Off in California, Jan 29, 2011, Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2011/01/paid-family-leave-pays-off-in.html.

[61] Sharon Lerner and Eileen Appelbaum, Business As Usual: New Jersey Employers’ Experiences With Family Leave Insurance, Demos, Jun 2014, http://www.demos.org/publication/business-usual-new-jersey-employers%E2%80%99-experiences-family-leave-insurance.

[62] Bartel, et al, “Assessing Rhode Island’s Temporary Caregivers Insurance Act: Insights from a Survey of Employers,” Jan 2016, http://www.dol.gov/asp/evaluation/completed-studies/AssessingRhodeIslandTemporaryCaregiverInsuranceAct_InsightsFromSurveyOfEmployers.pdf.

[63] Employers Association of New Jersey, “Who We Are,” webpage viewed Apr 28, 2016, http://www.eanj.org/about/.

[64] Employers Association of New Jersey, “Most Employers Prepared for Family Leave Insurance but Many Small Firms Are Still in the Dark,” Jun 2009, http://www.eanj.org/newsroom/most-employers-prepared-family-leave-insurance-many-small-firms-are-still-dark.

[65] “Implementation and Early Outcomes of the City of Seattle Paid Sick and Safe Time Ordinance,” prepared by Jennifer Romich et al, University of Washington, for the Seattle City Auditor, April 2014, http://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/CityAuditor/auditreports/PSSTO_ReportSummaryOCAEmail.pdf.

[66] Paid Family Leave California, “New Poll Finds Just 36% Of California Voters Aware Of State’s Paid Family Leave Program,” Jan 14, 2015, http://paidfamilyleave.org/news-room/press-releases/new-poll-finds-just-36-of-california-voters-aware-of-states-paid-family-leave-program.

[67] NJ.com “You probably don’t know NJ allows paid family leave, study says,” Mar 30, 2016, website viewed Apr 29, 2016, http://www.nj.com/politics/index.ssf/2016/03/paid_family_leave_law_works_but_few_know_about_it.html;

[68] Center for Women and Work, Rutgers University, “Policy in Action: New Jersey’s Paid Family Leave Program at Age Three,” Jan 2013, http://njtimetocare.com/sites/default/files/01_CWW%20Report-%20Policy%20in%20Action-%20New%20Jersey%27s%20Family%20Leave%20Insurance%20Program%20at%20Age%203.pdf.

[69] Suma Setty, Curtis Skinner, Renée Wilson-Simmons, “Protecting Workers, Nurturing Families: Building an Inclusive Family Leave Insurance Program: Findings and Recommendations from the New Jersey Parenting Project,” National Center for Children in Poverty, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, Mar 2016, http://www.nccp.org/publications/pub_1152.html.

[70] Setty, et al., “Protecting Workers, Nurturing Families” National Center for Children in Poverty, Mar 2016, http://www.nccp.org/publications/pub_1152.html.

More To Read

June 5, 2024

How Washington’s Paid Leave Benefits Queer and BIPOC Families

Under PFML, Chosen Family is Family

November 21, 2023

Why I’m grateful for Washington’s expanded Paid Family & Medical Leave

This one is personal.

February 10, 2023

Thirty Years of FMLA, How Many More Till We Pass Paid Leave for All?

The U.S. is overdue for a federal paid leave policy