Washington State has failed for years to make the investments necessary to promote educational opportunity and healthy communities because of our insufficient and unjust tax system. While some problems are masked during boom growth periods, they become starkly clear during recessions. Washington stands to learn from its mistakes in the Great Recession, as austerity and cuts caused Washington to lag behind other states in rebounding – to the extent that funding for state services did not reach pre-Great Recession levels when the coronavirus caused the 2020 shutdown.

Tax Diversity and Length of Recession Recoveries

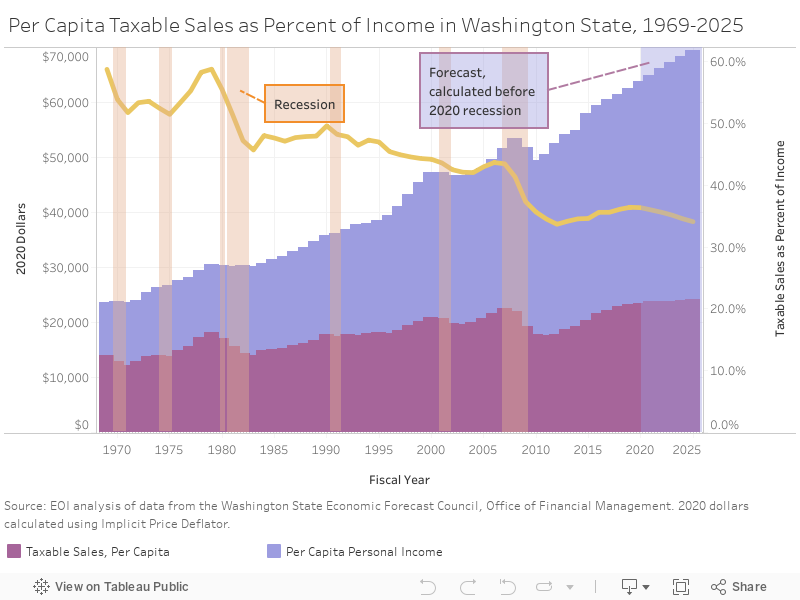

One major difference between Washington and other states’ tax systems is our state’s reliance on sales taxes for the bulk of its funds. Sales taxes accounted for 49.5 percent of the state’s general fund revenue in fiscal year 2019.[1] Through the middle part of the 20th century, when our economy was based largely on the consumption of goods, sales tax revenues largely kept up with personal income growth. For the last 40 years, however, that revenue stream has declined as the economy shifts from goods to services.[2]

While the state taxes construction labor, repair services, and some other services, the retail sales tax does not apply to the majority of services.[3] As Washington gets richer, taxable sales have remained relatively flat, after adjusting for inflation, while incomes have exploded.

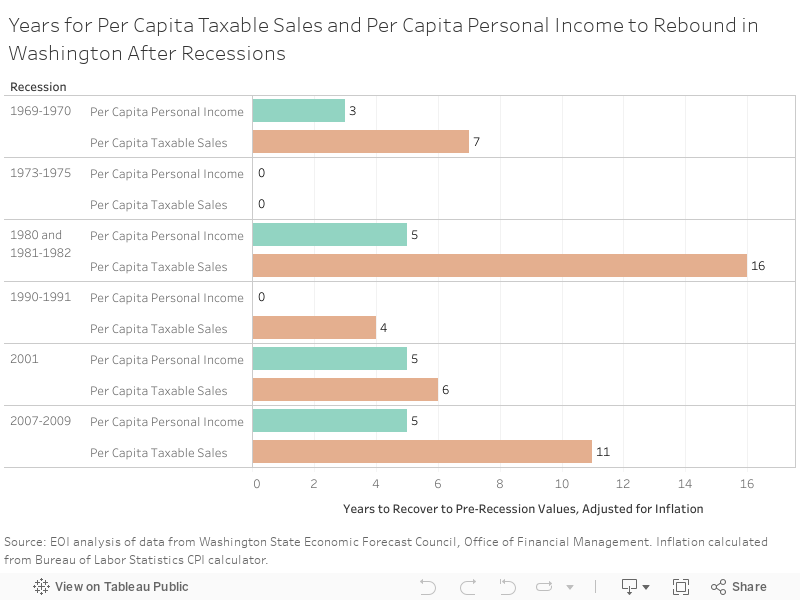

After recessions, it may take years for consumer confidence to rise again, and for sales to reach pre-recession levels. According to a study from the Pew Charitable Trusts, Washington took longer to recover tax revenue after the Great Recession than other states, most of which have a diverse mix of sales, income and capital gains taxes.[4] While the average state had a pre-recession peak in revenue in the third quarter of 2008 and recovered in the second quarter of 2013, Washington had a peak in the first quarter of 2008 and recovered in the first quarter of 2015 – almost two years longer. The Urban Institute found that the 2007-2009 hit sales-tax-reliant states unprecedentedly hard.[5]

In Washington, per capita incomes have rebounded from recessions much quicker than taxable sales, which has been generally true throughout the country. In the past six recessionary periods, taxable sales took on average 2.3 times longer to recover than income in Washington. Washington’s unreliable revenue stream is one of the main reasons that Seattle economist Dick Conway highlighted in rating Washington’s tax system 42nd in terms of stability in 2017.[6]

Washington’s proneness to recessions is forecasted to worsen. Because revenue from sales taxes is eroding, the Urban Institute predicts sales-tax-reliant states will continue to face anemic revenue growth compared with other states, causing escalating problems from recession to recession.[7]

Because of this growing gap between household incomes and taxable sales, states have attempted to expand the sales tax base to cover more goods and services for the past few decades, but these attempts have failed or been pared down significantly – partially because expanding sales taxes has proven extremely unpopular at the polls.[8]

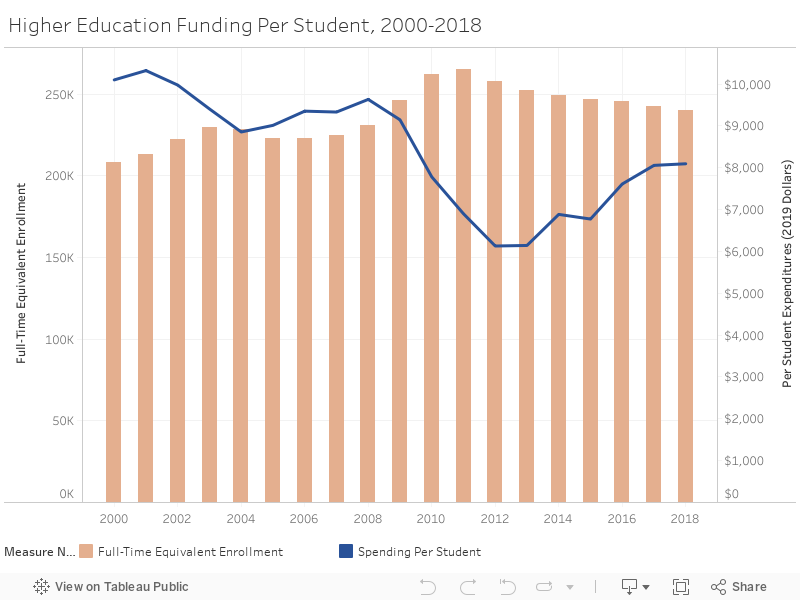

Impacts of Austerity

Washington made severe cuts to its budget in response to the Great Recession instead of increasing revenue to make up for the shortfall. The effect of that austerity lasted a very long time. Six years after the recession ended, the Washington Post reported: “So far, states have been slow to undo the cuts they made during the crisis. In Washington state, per-pupil spending remains 28 percent below pre-recession levels, while sticker prices at public four-year colleges is up 58 percent — and that’s all after adjusting for inflation.”[9]

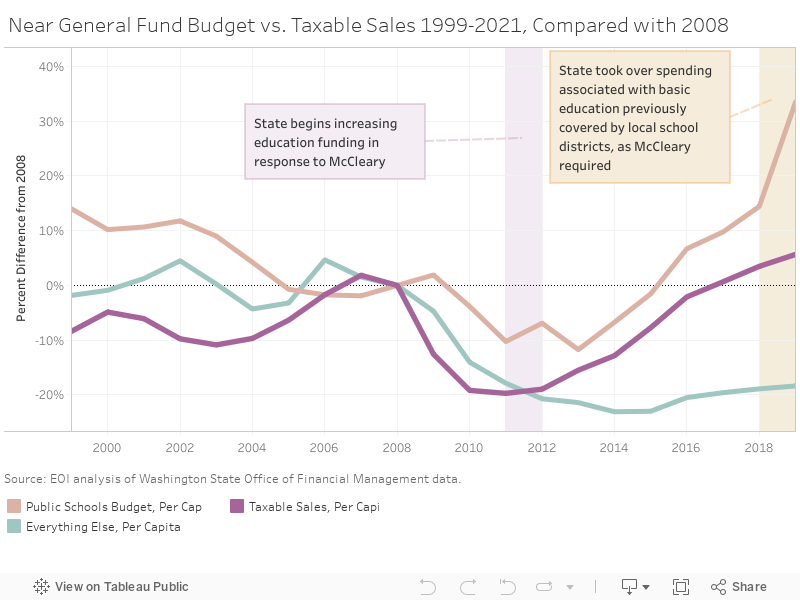

In fact, the impact of the budget cuts lingered through 2020. When looking at the budget per capita and adjusting for inflation, the Near General Fund only last year returned to its per capita levels of 2008. After the McCleary decision, the majority of the recovery gains went to K-12 funding. The funding for everything else, however, was still more than 18 percent lower per capita in 2019 than it was in 2008.

Unsurprisingly, the Near General Fund Budget and revenue from taxable sales correlate strongly. Although the budget has grown significantly in real dollars, Washington has gained more than a million people since 2008, not to mention the 19.1 percent inflationary change during that period – meaning that per capita, the hefty budget growth is an illusion.

In contrast, personal income in the state continued to grow at a fast clip, especially for the wealthy. Since the 1980s, inequality in our state has expanded due to income growth among the top 10 percent, particularly among the top 1 percent. Incomes for the vast majority of residents have stagnated, however.

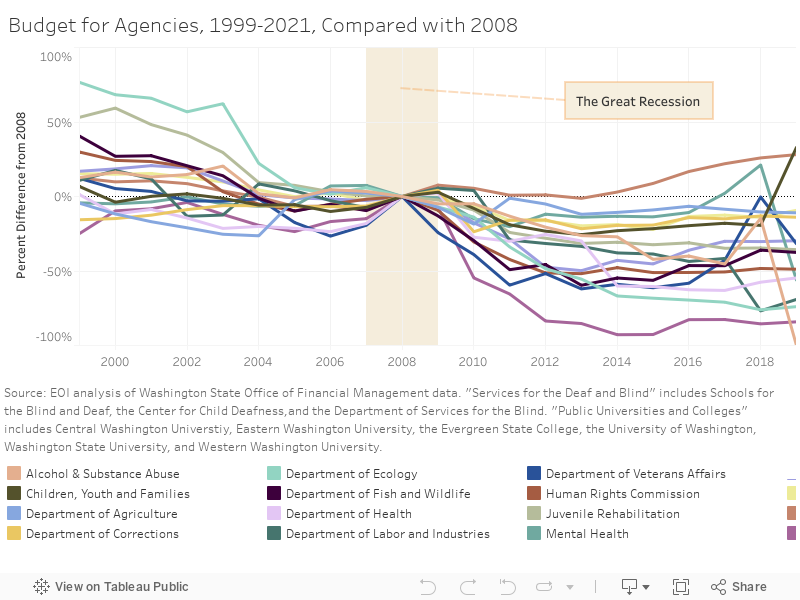

The lackluster rebound after the Great Recession coupled with an inability to collect revenue reflecting the larger, wealthier populace means that nearly every state agency had significantly less funding per capita in 2019 than in 2008.

While per capita funding for state parks and recreation was almost flat from 1999-2008, the funding has been about 80 percent lower than 2008 for the last eight years. For the Department of Health, it’s about 60 percent lower, and for the Department of Ecology it’s about 70 percent.

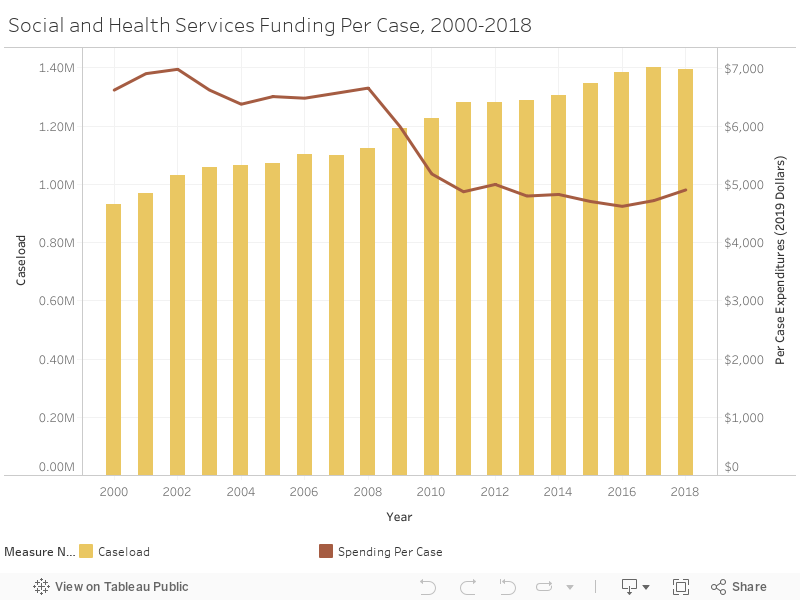

Looking more closely, the post-recession budgets have had a discrete effect on the funding for the Department of Social and Health Services. From 2000 to 2019, the amount of cases per year has increased 33 percent. Funding, however has not caught up. From 2000 to 2008, the budget per case averaged $6,639. From 2009 to 2019, the average was $5,029 – 32 percent lower.

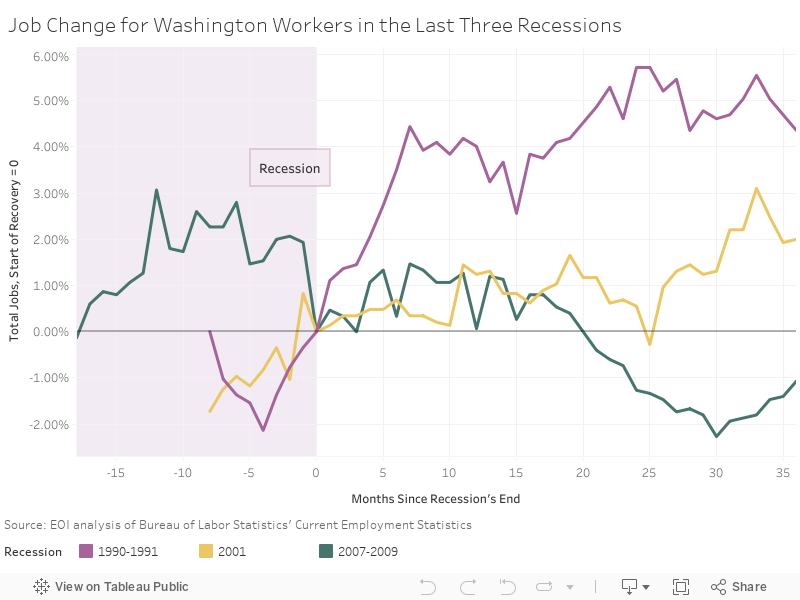

Austerity’s Effect on Jobs

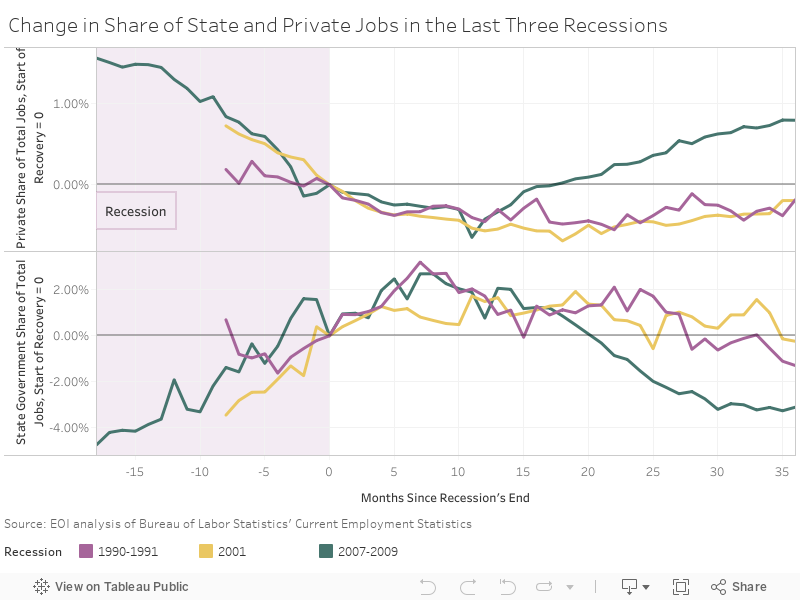

While Washington gained jobs during and after the 1990 and 2001 recessions, the opposite was true during the Great Recession. In fact, employment was still below pre-recession levels even three years after the Great Recession ended, despite gaining 150,000 new residents.

The most glaring weakness in the Great Recession recovery was the unprecedented public-sector job loss. Private sector job growth in the Great Recession recovery was better than in the other two. But the public sector saw massive job loss in the Great Recession recovery, largely due to budget cuts at the state level — a serious drag that was not weighing on earlier recoveries.

State government shed 1,600 jobs from June 2009 to June 2012. To keep the same ratio of state jobs to population, the state should have added 3,400.

In the long run, public-sector job cuts also cause job loss in the private sector. First, public-sector workers need good from the private sector. Firefighters need hoses, police officers need cars, and teachers need books. When public-sector jobs are lost, it stands to reason that the need for goods into these jobs will fall as well. Research shows that for every public-sector job lost, roughly 0.43 supplier jobs are lost.[10]

Second, the economic multiplier of state and local spending (not including transfer payments) is large – economic studies place it between 1.2 and 1.5.[11] This means that for every dollar cut in salary and supplies of public-sector workers, another $0.20 to $0.5 is lost in purchasing power throughout the rest of the economy.

According to research from the Economic Policy Institute, fiscal austerity explains why the most recent recovery took so long.[12] Per capita federal, state and local government spending in the first quarter of 2016 — 7 years into the recovery — was nearly 3.5 percent lower than it was at the trough of the Great Recession. That’s in stark contrast to the three recessions prior, when spending was 3 to 17 percent higher after the same amount of time.

This conclusion was echoed by many other economists. “One of the biggest drags on the recovery between 2009 and 2016 was cutbacks in state and municipal funding,” said Yakov Feygin, associate director of the Future of Capitalism Program at the Berggruen Institute. “You had increases in federal spending, but those were eaten up by austerity at the state level. It’s one of the primary reasons we had such a big drag on the recovery.”[13]

“State spending cuts translate into income losses for state employees and suppliers, while tax increases reduce the after-tax income of state residents,” said researchers from the Brookings Institute.[14] “Those income losses are likely to cause follow-on reductions in economic activity, both by directly and contemporaneously reducing aggregate demand for goods and services and by increasing the risk that current disruptions cause scarring that weighs on economic activity for a longer period.”

Footnotes

[1] Economic and Revenue Forecast Council. Washington State Economic and Revenue Forecast, Volume XLII, No. 4. 2019, p. 45.

[2] Church, Jonathan. “Explaining the 30-year shift in consumer expenditures from commodities to services, 1982–2012.” Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 2014.

[3] Washington Department of Revenue. Services subject to sales tax.

[4] Pew Charitable Trusts. “Fiscal 50: State Trends and Analysis.” March 1, 2018.

[5] Francis, Norton and Frank Sammartino. “Governing with Tight Budgets: Long-Term Trends in State Finances.” Urban Institute, 2015, p. 9-10.

[6] Conway, Dick. “Washington State and Local Tax System: Dysfunction & Reform.” Dick Conway & Associates, 2017, p. 17.

[7] Norton, op. cit.

[8] Farmer, Liz. “Why States’ Increasing Reliance on Sales Taxes Is Risky.” Governing, September 22, 2015.

[9] Guo, Jeff. “College will soon be a ton cheaper in Washington state. Thank Microsoft.” Washington Post, July 2, 2015.

[10] Pollack, Ethan. “Dire Straits: State and Local Budget Relief Needed to Prevent Job Losses and Ensure a Robust Recovery.” EPI Briefing Paper No. 252, Economic Policy Institute, 2009, p. 5.

[11] Scott, Katie. “Keeping up with the Economy: Local Economic Multipliers.” Pulse, National Association of State Procurement Officials, June 4, 2019.

[12] Bivens, Josh. “Why is recovery taking so long – and who’s to blame?” Economic Policy Institute, August 11, 2016.

[13] Blumgart, Jake “The pandemic is pushing US city budgets into a new age of austerity.” CityMetric, May 5, 2020.

[14] Fiedler, Matthew and Wilson Powell III, “States will need more fiscal relief. Policymakers should make that happen automatically.” Brookings Institute, April 2, 2020.

More To Read

September 24, 2024

Oregon and Washington: Different Tax Codes and Very Different Ballot Fights about Taxes this November

Structural differences in Oregon and Washington’s tax codes create the backdrop for very different conversations about taxes and fairness this fall

September 6, 2024

Tax loopholes for big tech are costing Washington families

Subsidies for big corporations in our tax code come at a cost for college students and their families

July 19, 2024

What do Washingtonians really think about taxes?

Most people understand that the rich need to pay their share