Summary

By many measures, Washington’s economy has soared since the Great Recession. The state has added over 400,000 jobs since 2008 – more than making up for previous losses – and average hourly wages have climbed 13 percent after adjusting for inflation. However, those rosy numbers mask the fact that sluggish wage growth, increasing inequality and rising prices are leaving many Washington residents struggling.

Strong job growth can provide broad-based economic opportunity, but only if accompanied by equitable wage growth – and on the equity score, Washington’s economy is not performing well. Since the end of the Great Recession, the top end of wage earners have enjoyed substantial gains, while two out of three jobs have seen average wages increase just 1 percent, or $387 annually.

The stall in wage growth for most workers since the Great Recession is part of a longer-term national trend. While economic productivity in the state has increased more than 53 percent since 1979, the benefits of those gains flowed increasingly to the top in the form of higher wages and profits for corporate shareholders. As a center for the tech industry, wage inequality in Washington now far outpaces that for the U.S. as a whole.

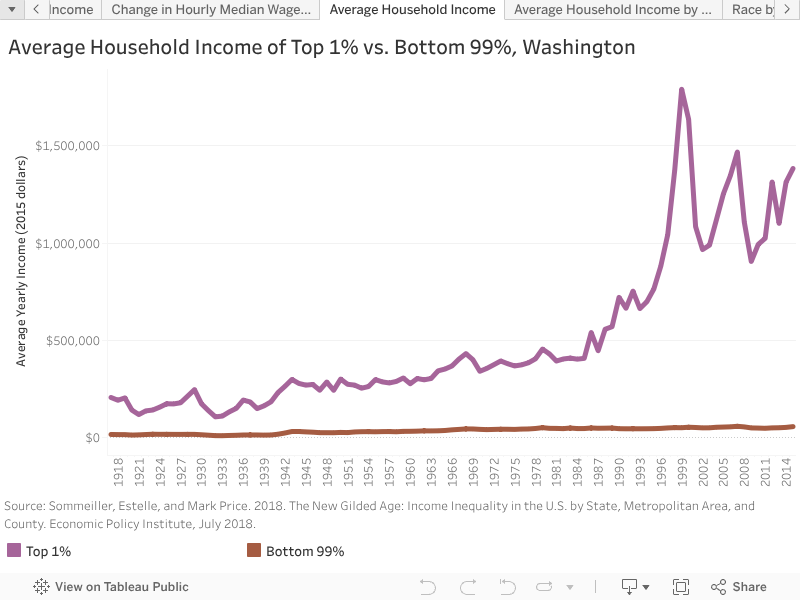

Growth in investment income for the top 1 percent is also a prime driver of income inequality. Between 1945 and 1973, while recessions and expansions came and went, the state’s top 1 percent captured just 8.4 percent of overall income growth. Since 1973, the richest 1 percent has captured 43 percent of income growth, leaving far less for everyone else.

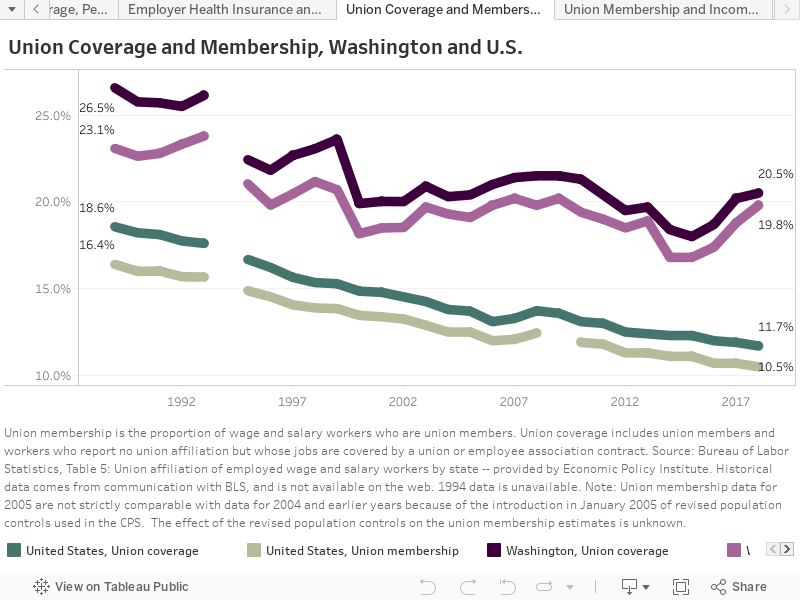

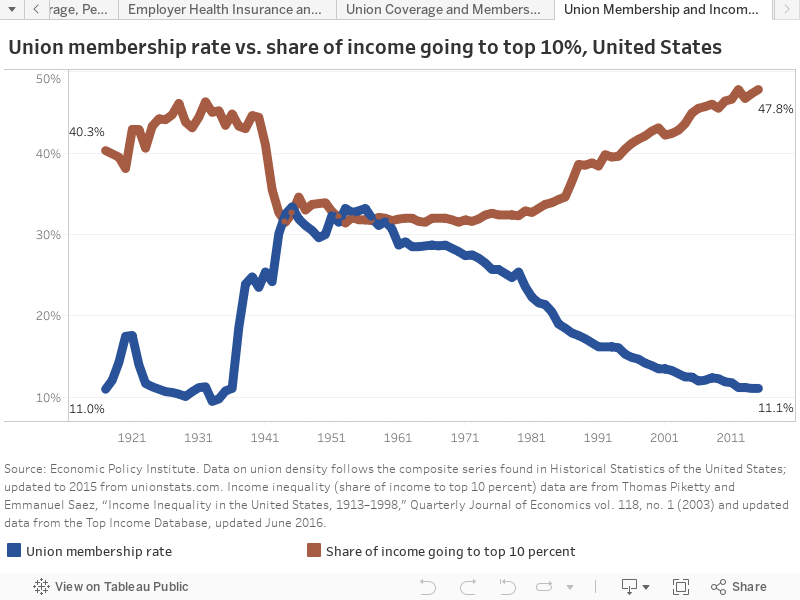

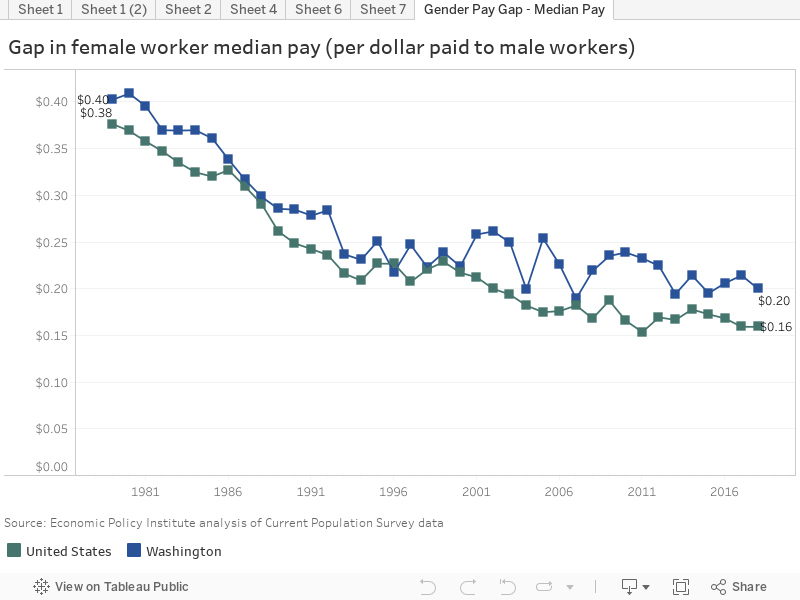

Several other factors are contributing to stagnating wages and growing inequality, including declining unionization, and gaps in pay by gender and race rooted in historic barriers and systemic discrimination.

The result: most working people and families – whether in Seattle, Longview, or Yakima – are finding it harder to make ends meet. Strong job growth and rising incomes for those at the top are pushing up prices and making Washington a more difficult place to live, work, and raise a family. Even after adjusting for inflation, costs for rent, home ownership, health care, child care, and higher education have outpaced modest increases in median family income.

Washington voters and policymakers have already taken a number of steps that protect hard-working families up and down the income ladder and mitigate the negative impacts of inequitable economic growth – but local and state leaders could do much more.

While our state’s economy is subject to some external forces beyond our immediate control, we can still make a number of public policy choices that will protect workers and families, overcome barriers of systemic discrimination, improve economic stability, and promote equality of opportunity for all people. Several such steps are outlined in the conclusion of this brief.

Jobs boom, but wages fizzle (for most)

By many measures, Washington’s economy has soared since the Great Recession. Since 2008, the state has added over 404,000 total nonfarm jobs, and average hourly wages climbed 13 percent after adjusting for inflation. But while more people are bringing home paychecks compared to a decade ago, wage growth for most workers has been anemic at best. In the state’s largest eight employment sectors – which comprise 68.5 percent of all nonfarm employment and have contributed three-fourths of new jobs since 2008 – average wages have increased just $853, or 1.7 percent, annually.[1]

A single subsector, Nonstore Retail (think Amazon), accounts for nearly half of that wage increase – but just 1.6 percent of the state’s total jobs in 2018. Put another way: excluding Nonstore retail, average wages have increased only $387 (0.8 percent per year) for 67 percent of Washington workers. And while at first glance, manufacturing looks like a source of relatively high-wage employment, outside of the aerospace subsector (where wages are above the state average but employment is flat), wages are below average, and employment has declined since 2008.

Job and Wage Growth 2008-18: High Employment Sectors, Washington

| Sector | Total Jobs (% of total) 2018 |

New Jobs (% of total) 2008-18 |

Avg. Wage (versus WA avg.) 2018 |

Avg. Yearly Wage Increase (%) 2008-18 |

| Health Care and Social Assistance | 426,350 (12.5%) |

79,658 (19.7%) |

$53,015 (-$24,025) |

$323 (0.6%) |

| Retail Trade | 392,375 (11.5%) |

65,008 (16.1%) |

$55,168 (-$21,872) |

$1,999 (5.7%) |

| Retail Trade (less Nonstore retailers)* | 339,217 (10.0%) |

23,724 (5.9%) |

$34,475 (-$42,565) |

$133 (0.4%) |

| Nonstore retailers* | 53,158 (1.6%) |

41,284 (10.2%) |

$176,373 (+$99,333) |

$8,722 (9.8%) |

| Local Government | 356,225 (10.5%) |

32,592 (8.1%) |

$57,368 (-$19,672) |

$314 (0.6%) |

| Accommodation and Food Services | 287,138 (8.5%) |

51,196 (12.7%) |

$22,948 (-$54,092) |

$320 (1.6%) |

| Manufacturing | 284,588 (8.4%) |

-6,587 (-1.6%) |

$85,217 (+$8,177) |

$1,160 (1.6%) |

| Manufacturing (less aerospace) | 201,900 (5.9%) |

-6,283 (-1.6%) |

$65,465 (-$11,575) |

$435 (0.7%) |

| Aerospace | 82,688 (2.4%) |

-304 (-0.1%) |

$130,927 (+$53,887) |

$2,615 (2.5%) |

| Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services | 211,175 (6.2%) |

44,375 (11%) |

$101,164 (+$24,414) |

$1,690 (2.0%) |

| Construction | 210,150 (6.2%) |

9,692 (2.4%) |

$68,115 (-$8,925) |

$870 (1.5%) |

| Administrative and Support Services | 158,025 (4.7%) |

25,283 (6.3%) |

$50,167 (-$26,873) |

$902 (2.2%) |

| Total/Average | 2,326,026 (68%) |

301,217 (75%) |

$59,815 (-$17,225) |

$853 (1.7%) |

Source: Washington State Employment Security Department: 1) Employment Estimates (WA-QB, not seasonally adjusted) through August 2018, and 2) Covered Employment (QCEW) through 2018 Q1. *2018 Retail Trade (less Nonstore retailers) and Nonstore retailers employment data is estimated based on 2017 data; wages shown are through 2017 Q4, inflation-adjusted to 2018.

Meanwhile, a handful of high-wage job categories have been reaping most of the gains of a growing economy. Four sectors (Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services; Information; Finance and Insurance; and Management of Companies and Enterprises) comprise only 14 percent of nonfarm employment, and have contributed just 20 percent of new jobs since 2008 – but wages have grown an average $3,295 (3.4 percent) yearly. Wage increases in the Software Publishing subsector are particularly outsized, averaging $7,284, or 4.2 percent, per year. But even excluding that sector, wages increased an average $1,930, or 2.9 percent, in these sectors each year.[2]

Job and Wage Growth 2008-18: High Wage Sectors, Washington

| Sector | Total Jobs (% of total) 2018 |

New Jobs (% of total) 2008-18 |

Avg. Wage (versus WA avg.) 2018 |

Avg. Yearly Wage Increase (%) 2008-18 |

| Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services | 211,175 (6.2%) |

44,375 (11.0%) |

$101,164 (+$28,124) |

$1,690 (2.0%) |

| Information | 131,488 (3.9%) |

25,871 (6.4%) |

$204,008 (+$126,968) |

$7,896 (6.3%) |

| Information (less Software publishers) | 67,276 (2.0%) |

12,601 (3.1%) |

$162,820 (+$85,780) |

$8,386 (10.6%) |

| Software publishers | 64,212 (1.9%) |

13,270 (3.3%) |

$247,104 (+$170,064) |

$7,284 (4.2%) |

| Finance and Insurance | 99,325 (2.9%) |

-475 (-0.1%) |

$95,765 (+$18,725) |

$845 (1.0%) |

| Management of Companies & Enterprises | 45,525 (1.3%) |

10,808 (2.7%) |

$128,164 (+$51,124) |

$2,309 (2.2%) |

| Total/Average | 487,513 (14%) |

67,764 (20%) |

$130,323 (+$53,283) |

$3,295 (3.4%) |

Source: Washington State Employment Security Department: 1) Employment Estimates (WA-QB, not seasonally adjusted) through August 2018, and 2) Covered Employment (QCEW) through 2018 Q1.

Washington is growing more unequal, more quickly, than the nation

Wages

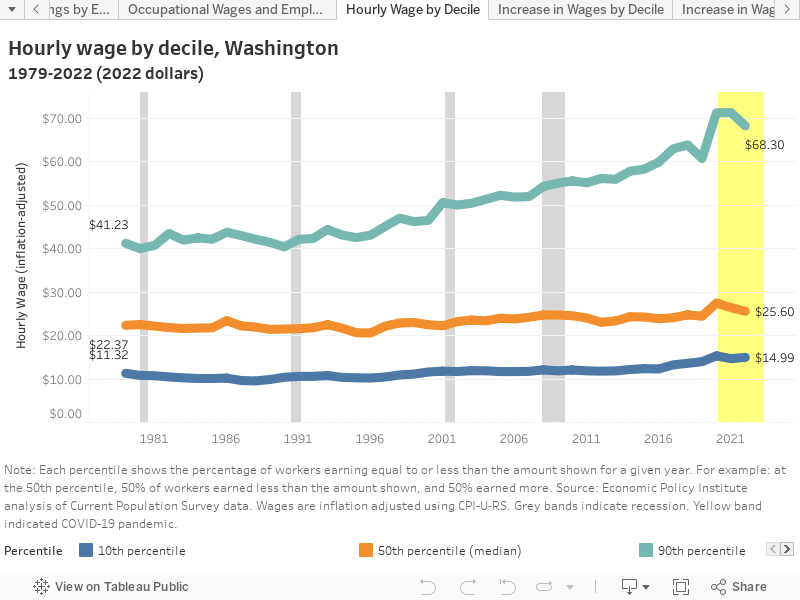

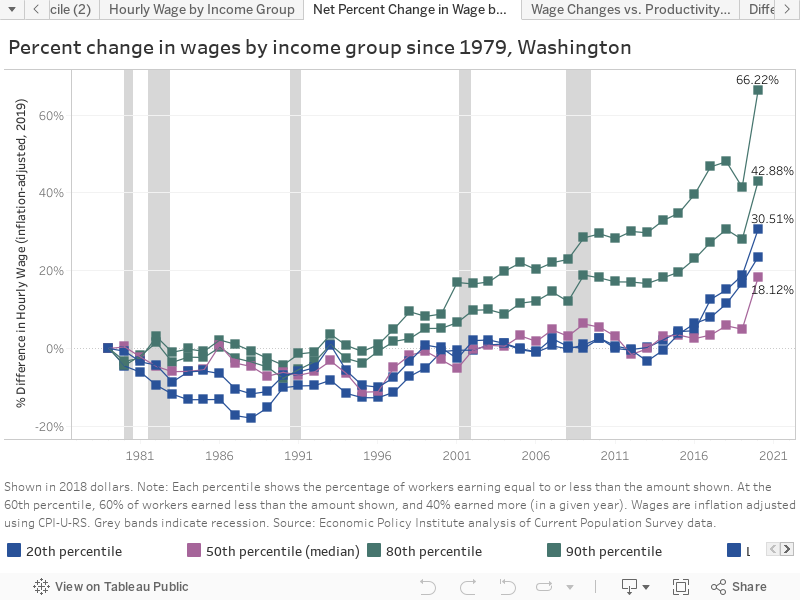

Since 2008, wages have stalled for two-thirds of Washington’s jobs, while already high-wage jobs have seen big gains. However, that trend goes back much further than the Great Recession. In fact, since 1979, wages for the bottom 60 percent of Washington workers have increased just $1.03/hour after adjusting for inflation; meanwhile, the top 10 percent have seen hourly wages jump nearly $18 per hour.[3]

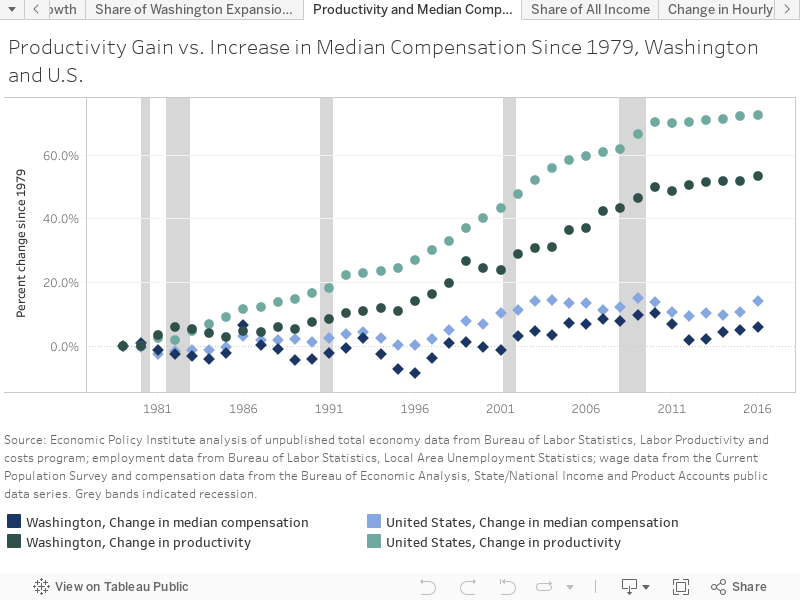

Between 1979 and 2016, Washington’s economic productivity increased more than 53 percent – but median compensation (where 50 percent of wage earners earn less, and 50 percent earn more) grew just 6 percent, as the benefits of growth flowed increasingly to the top in the form of higher wages and corporate profits.[4],[5]

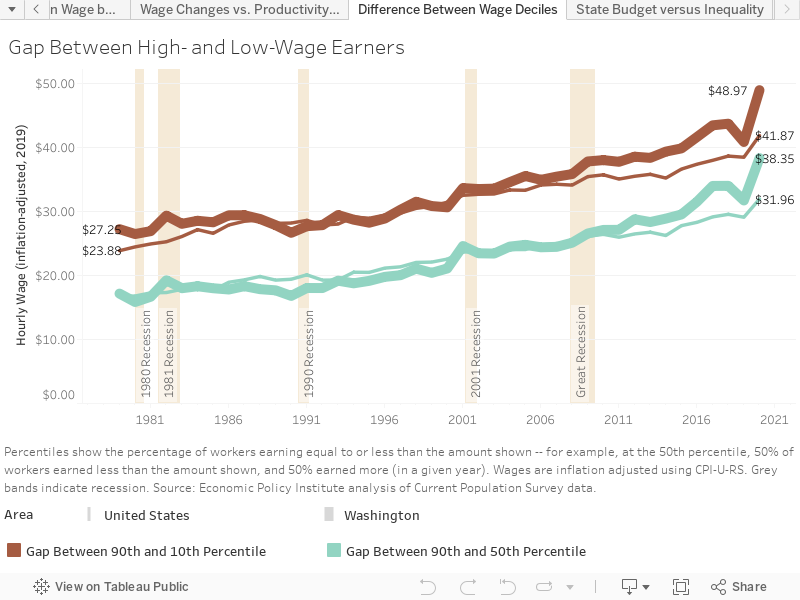

Throughout the 1980’s, the relative difference in hourly wages between high- and low-wage workers was relatively stable in Washington – ranging from $25 to $27/hour (top 10 percent vs. lowest 10 percent), and $16 to $18/hour (top 10 percent vs. bottom 50 percent).

That’s not to say all was well during this time. While wages fluctuated – and on net, declined to some degree for workers at all levels – as a percentage of their hourly wage, the lowest-paid 20 percent of workers (who were earning less to begin with) saw bigger drops and smaller increases in pay than did those in higher wage brackets. Washington’s landmark voter-approved 1998 minimum wage law helped limit losses for low-wage workers, and in 2017 (after another voter-approved minimum wage increase), the lowest-paid 20 percent of workers have finally begun to make some headway.[6]

During the 1990s, the wage gap between the top 10 percent and bottom 10 percent in Washington began to grow, eventually matching U.S. levels; by 2001, the gap between the top 10 percent and bottom 50 percent had done the same. That trend intensified in the years leading up to the Great Recession, as the state’s top 10 percent/bottom 10 percent gap began growing faster than that of the U.S. In the years since the Great Recession, the top 10 percent/bottom 50 percent gap has also grown much faster in Washington than nationwide.

In Washington, growth in income inequality has far outpaced the U.S. as a whole. As of 2018, the difference in hourly wages between high- and median-wage workers (top 10 percent vs. bottom 50 percent) in Washington now exceeds $33/hour. The gap between high- and low-wage workers (top 10 percent vs. lowest 10 percent) has grown to $43/hour.

Income

Hourly earnings are the most important source of total income for many households. But Social Security, pensions, investment income, and other sources also contribute. Investment income in particular contributes substantially to inequality growth. As of 2015, it takes a yearly income of $451,395 to be in the top 1% in Washington. The average income of the state’s top 1 percent ($1,383,223) was 24 times that of the bottom 99 percent ($57,100).

It hasn’t always been this way. Even during the so-called Roaring Twenties (late 1920’s) – during which the share of America’s wealth controlled by the richest of the rich increased rapidly – the top 1 percent brought in just 12 times the income of the bottom 99 percent. Post-WWII (from 1945 to 1973), Washington’s top 1 percent captured only 8.4 percent of overall income growth, such that as of 1973, incomes for the richest 1 percent of households were 9 times that of the other 99 percent. Since then, however, the top 1 percent has captured 43 percent of income growth, leaving far less for people further down the income ladder.[7]

Why the gap between rich and poor continues to grow

Declining Unionization

While no single factor is entirely responsible for the growth in inequality, declining unionization has been a contributing influence.[8] Following the passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935, the spread of collective bargaining led to decades of faster and fairer economic growth that persisted until the late 1970s.

Since the 1970s, however, declining unionization has fueled rising inequality and stalled economic progress for the middle class. Nationally from 1972 to 2007, one-third of the rise in wage inequality among men, and one-fifth of the rise in wage inequality among women, is attributable to declining unionization. Among men, the erosion of collective bargaining has been the largest single factor driving a wedge between middle- and high-wage workers.[9]

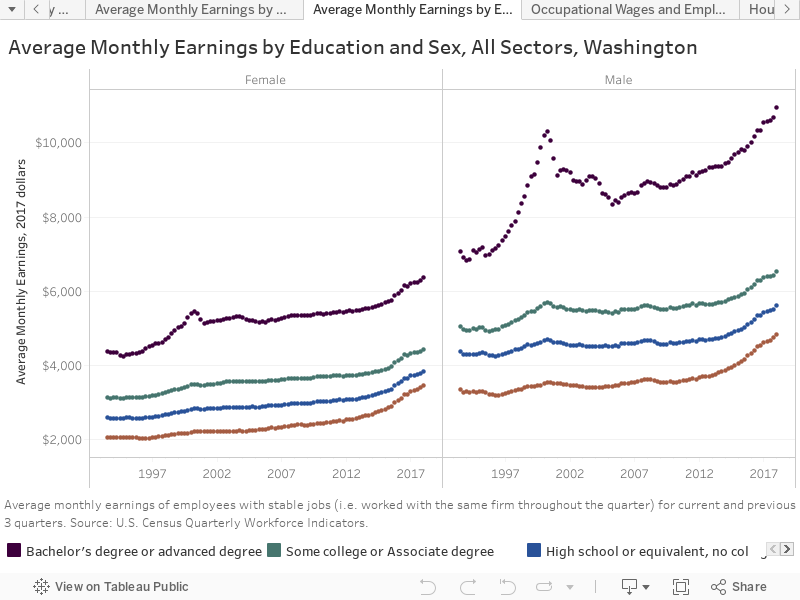

Gender Pay Discrimination

Another persistent source of income inequality is the gender pay gap. In Washington, a typical woman (or one earning median wage) is paid 22 cents less per dollar paid to a typical man.[10] While the gender pay gap has declined since 1979, the state has not made any significant or lasting progress in closing the gap since the late 1990’s.

The gender pay gap is not an education gap – nor is it solely a product of having fewer women in some industries than others. At every level of education, women are paid less than similarly educated men – and the wage gap rises with additional education. The gap also exists in all industries – including those in which more women are employed than men.[11]

Gap in Average Monthly Wages versus Male Workers, All Industries, Washington

| Sector | Ratio of Female to Male Workers |

Gender Wage Gap (Average monthly wage) |

| Health Care and Social Assistance | 3.34 | $1,898 |

| Educational Services | 2.23 | $855 |

| Finance and Insurance | 1.67 | $3,520 |

| Other Services (except Public Administration) | 1.26 | $1,221 |

| Accommodation and Food Services | 1.16 | $279 |

| Management of Companies and Enterprises | 1.16 | $2,007 |

| Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation | 1.04 | $843 |

| All NAICS Sectors | 0.93 | $2,013 |

| Retail Trade | 0.92 | $1,452 |

| Real Estate and Rental and Leasing | 0.91 | $914 |

| Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services | 0.87 | $2,694 |

| Public Administration | 0.80 | $1,248 |

| Admin. & Support and Waste Mgmt. & Remed. | 0.71 | $969 |

| Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting | 0.56 | $736 |

| Information | 0.48 | $4,781 |

| Utilities | 0.44 | $2,264 |

| Transportation and Warehousing | 0.44 | $1,203 |

| Wholesale Trade | 0.43 | $1,680 |

| Manufacturing | 0.37 | $1,359 |

| Construction | 0.22 | $1,447 |

Source: U.S. Census Quarterly Workforce Indicators, Full Quarter Employment (Stable); monthly wage calculated as 3-quarter weighted average for 2017 Q1 to 2017 Q3.

Racial Pay Discrimination

The National Picture

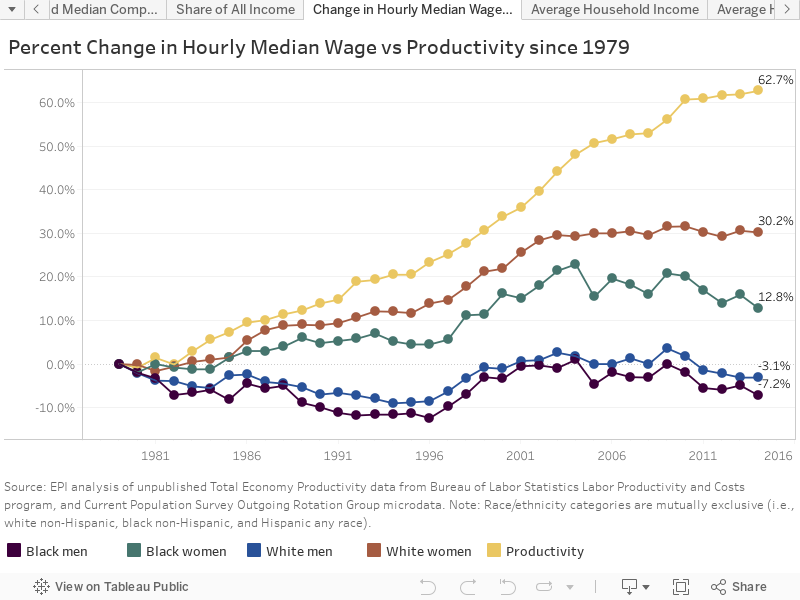

All demographic groups are experiencing growing income inequality and slowing growth in living standards. At the national level, since 1979 median hourly real wage growth has fallen short of productivity growth for all groups of workers, regardless of race or gender. However, these wage trends are markedly different for men than for women, and for blacks relative to whites.

Median hourly wages for both white and black men have fallen, with black men suffering larger losses (7.2 percent, compared a 3.0 percent loss for white men). While median hourly wages of black and white women have increased, white women’s wages grew much more (30.2 percent) than those of black women (12.8 percent).[12]

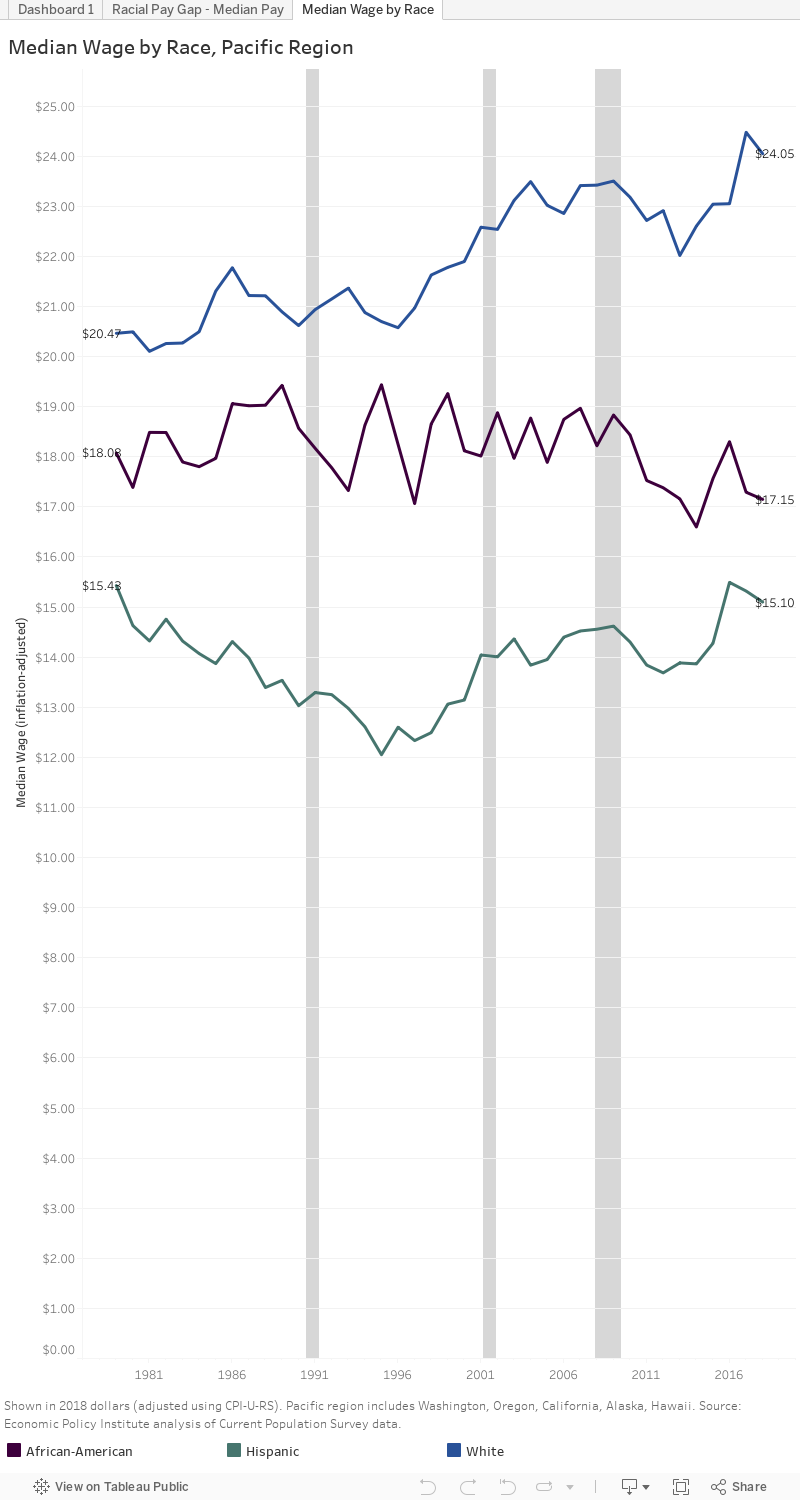

The Pacific Region

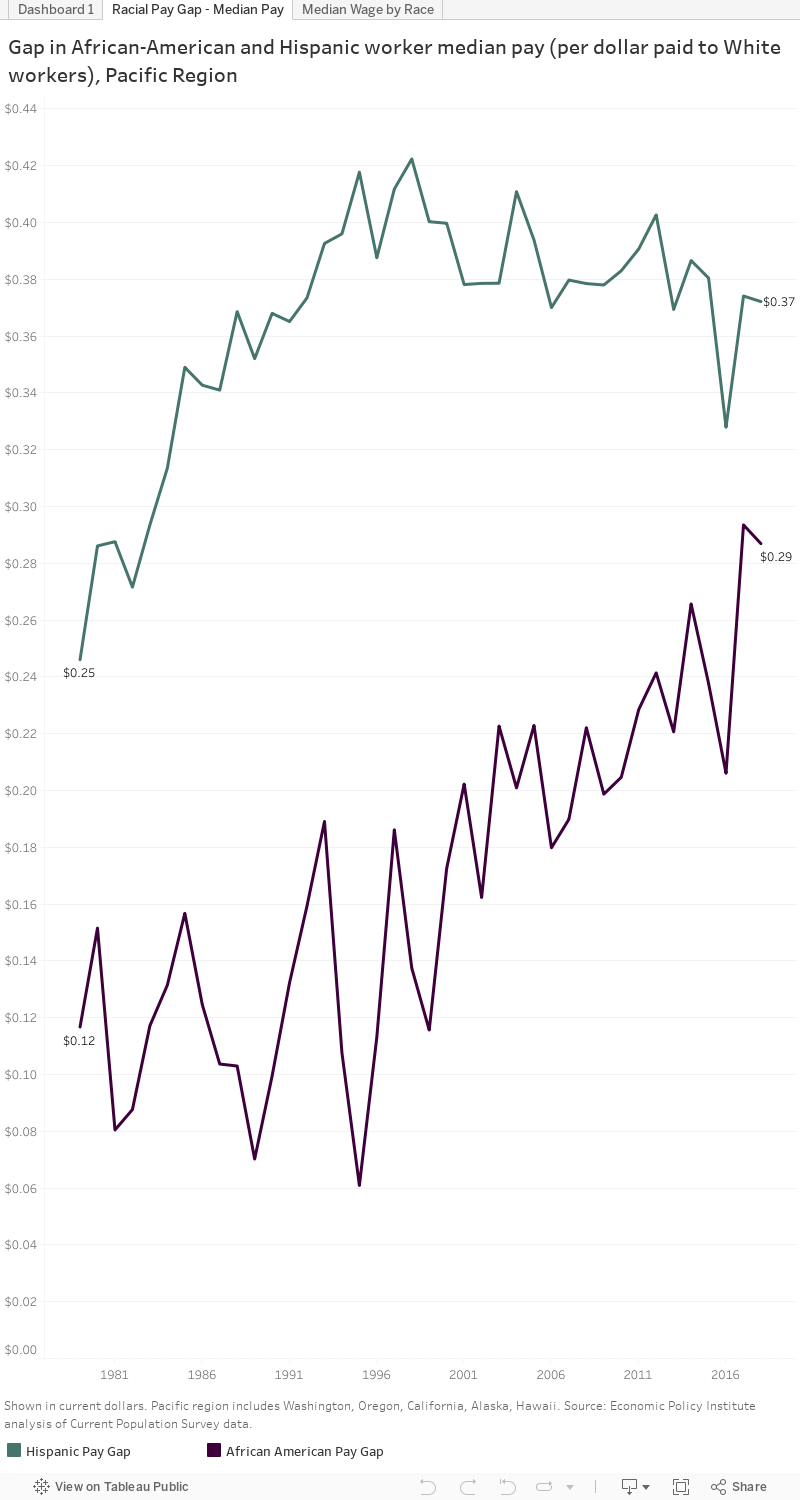

In the Pacific region of the U.S. (Washington, Oregon, California, Alaska, Hawaii), pay disparities by race and ethnicity have grown relative to 1979 levels. The median wage for White workers increased to $24.05/hour (+$3.58), while for Hispanic and Black workers it declined to $15.10/hour (-$0.33) and $17.15/hour (-$0.93), respectively.[13]

Put another way: in 2018 a typical (or median) Black worker was paid 29 cents less, and a Hispanic/Latinx worker 37 cents less, per dollar paid to a typical White worker. Since 1979, that gap has grown by 142 percent for Black workers, and for Hispanic/Latinx workers the gap has grown by nearly 50 percent.

Washington State

In Washington, the gap in average monthly wages between White workers and workers who are people of color grew dramatically between 1990 and 2017 (save for workers of Asian descent, a subset of whom are employed in very high-wage information, technology and professional sectors). In 2017 alone, the racial gap cost workers of color an average $12,228 to $20,838/year.[14]

Gap in Average Monthly Wages versus White Workers, All Industries, Washington State

|

Avg. monthly wage (2017 dollars) |

Gap in avg. monthly wage compared to White workers |

Equivalent yearly wage gap |

Increase in wage gap | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity |

1990 Q2 |

2017 Q2 |

1990 Q2 |

2017 Q2 |

1990 |

2017 |

|

| Amer. Indian/ Alaska Native | $2877 | $3961 | $833 | $1448 | $9996 | $17,376 | 74% |

| Asian | $3263 | $6551 | $447 | -$1142 | $5364 | n/a | n/a |

| Black or African American | $3112 | $3876 | $598 | $1533 | $7176 | $18,396 | 156% |

| Hisp./Latinx | $2614 | $3673 | $1096 | $1737 | $13,152 | $20,838 | 58% |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | $2816 | $3825 | $894 | $1584 | $10,728 | $19,008 | 77% |

| Two or More Race Groups | $3058 | $4390 | $652 | $1019 | $7824 | $12,228 | 56% |

| White (not Hisp./Latinx) | $3710 | $5409 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

Source: U.S. Census Quarterly Workforce Indicators, Full Quarter Employment (Stable), second quarter average monthly wages. Inflation adjusted to 2017 dollars using CPI-U-RS.

As with the gender pay gap, workers of color cannot educate themselves out of pay disparities. Nationally, as of January 2017, average hourly wages for White college graduates are far higher ($31.83) than for Black college graduates ($25.77) – and the national unemployment rate for Black college graduates was 4.0 percent, compared to 2.6 percent for White college graduates.[15],[16]

It’s getting harder for families to make ends meet

Stagnant wages and growing income inequality (driven by declining unionization and gaps in pay by gender and race) mean that most working people and families – whether in Seattle, Longview, or Yakima – are finding it harder live, work, and/or raise a family. Even after adjusting for inflation, costs for rent or home ownership, health care, child care and higher education have outpaced modest increases in median family income.

Housing

Housing is less affordable in Washington than it was a decade ago. Adjusted for inflation, median monthly rental costs in Washington have climbed 26.7 percent ($256/month) since 2007 – from 14.7 percent ($960/month) to 17.2 percent ($1216/month) of median family income. There is some local variation, but the trend is the same in all of Washington’s most populous areas. Over the same period, median rent climbed 42 percent ($460/month) in King County and 11.3 percent ($88/month) in Spokane.[17]

Median home prices have also climbed dramatically since bottoming out in 2011. At that time, the median (typical) home in Washington cost 3.3 times median family income. Today, such a home costs 4.1 times median family income. As with rental costs, there are local differences – but the upward trend is consistent. In King County, median home prices have far exceeded their previous peak, and now cost 5.7 times the median income for that area. In Spokane County, the cost of a home has risen from 2.8 to 3 times that of local median income.[18]

Transportation

As affordable housing has become more expensive in job centers (urban areas), more people have been forced to live further from work and face the higher time and money costs of a longer commute. The number of Washingtonians with a commute over 45 minutes increased 45.5 percent between 2006 and 2017 – while the number with a commute of less than 15 minutes decreased by 1.2 percent.[19]

Change in Number of Total Commuters by Average Commute Time, Washington, 2006-2017

| 0-15 minutes |

15-30 minutes |

30-45 minutes |

45+ minutes |

Total |

|

| Percent Change | -1.2% | +14.4% | +23.9% | +45.5% | 16.5% |

| Numeric Change | -10,034 | 147,538 | 135,517 | 194,497 | +467,518 |

Source: American Community Survey 1-year estimates, Travel Time To Work For Workplace Geography

Child Care

High quality, affordable child care is critical for working parents earning a living. In a two-parent household, only a fraction of Washington’s jobs pay enough for one parent to support an entire family – and for single working parents, child care is the only way to hold down a full-time job. It is just as important to an unemployed parent, as it provides time to attend school or get job training, or look for work. Employers rely on it as well – without child care, much of the labor market would dry up.

But despite its importance to our economy, families and communities, child care is growing less affordable. Accounting for inflation, average monthly costs for all ages of child care have grown significantly since 2005.[20]

Health Care

Economic, family and community health all depend on having access to affordable health care. Timely medical care reduces costs for workers and families, improves health outcomes and productivity, and reduces fiscal burdens and the risk of bankruptcy.

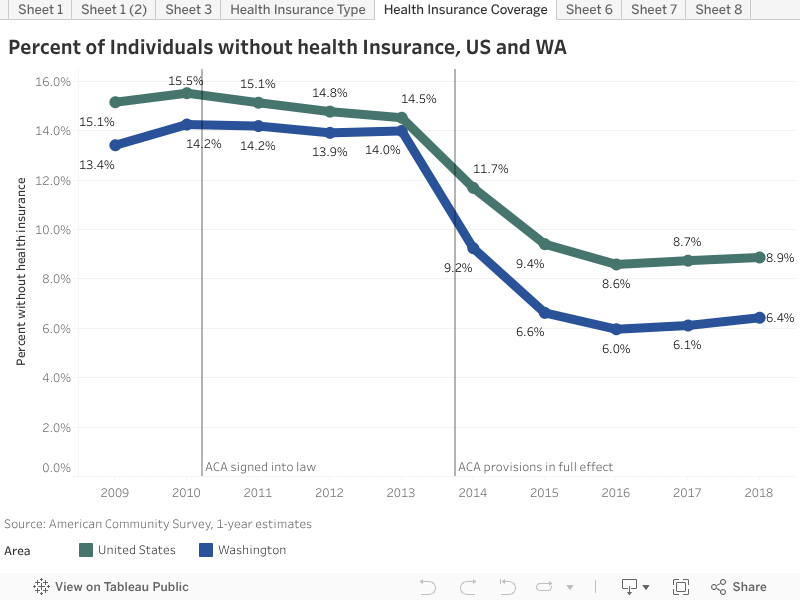

As the federal Affordable Care Act and related state legislation have come into full effect, the number of uninsured Washington residents has declined by 49 percent: 532,500 fewer people were uninsured in 2017 than in 2009. However, costs related to health insurance (deductibles, copayments and coinsurance) are rising.

Higher Education

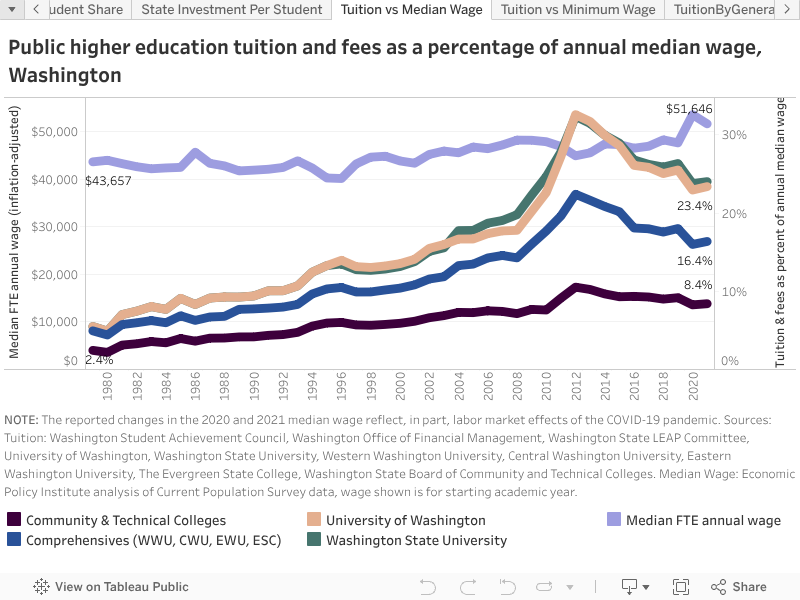

Washington’s 34 community and technical colleges and 6 universities collectively serve an estimated 240,000 full-time equivalent students.[21] Baby Boomers were able to work a summer minimum-wage job to pay for their tuition. However, in the 1980s, legislators began steadily cutting state investment in higher education. Today, the cost of a degree from one of Washington’s public colleges or universities often requires loan amounts that cause the state’s young people to postpone marriage, homeownership, children, and the American Dream.

What we can do to improve Washington’s economy

Strong employment growth can promote economic opportunity – but only with the right public policy choices. We need to pursue sustainable economic development policies and public investments that promote worker bargaining power, strong communities, and more equitable access to opportunity. These include boosting public investments in child care, education, housing, and health care.

In the long run, stopping or reversing rising inequality will require enacting policies that both spur faster wage growth for low- and middle-wage workers and also rein in the perpetuation of privilege and power by wealthy elites. Washington voters and policymakers have already taken a number of steps that protect hard working families up and down the income ladder and mitigate the negative impacts of inequitable economic growth, including:

- A minimum wage well above the federal level, with cities able to set higher wages;

- Paid sick and safe leave protections for most workers;

- A paid family and medical leave program that will provide extended paid leaves for serious health conditions or to care for a new child beginning in 2020;

- Pregnancy accommodation and updated equal pay protections; and

- Prevailing wage standards and protections for the rights of workers to collectively bargain.

These policies earned Washington Oxfam’s number two ranking after the District of Columbia as the best state to work.[22] Nevertheless, our local and state leaders could do much more, including:

- Updating rules defining which workers are protected by minimum wage, paid sick leave, and overtime laws, to ensure fair compensation for hours worked, expand the right to earn paid sick time, and enable workers to better balance their jobs with time for maintaining health, family, and community.

- Creating fair work scheduling standards (the city of Seattle provides an existing model), and rigorously enforcing wage laws aimed at preventing wage theft.

- Increasing enforcement of antidiscrimination laws in hiring, promotion, and pay.

- Ending policies that lead to mass incarceration, and prevent access to jobs and secure housing for the formerly incarcerated.

- Instituting drug price transparency and restrictions on surprise billing in order to control health care costs and protect people from medical debt.

Other needed improvements will require increased state investments – but Washington’s regressive tax code already limits funding for essential public services, and hurts those who are already struggling. In 2019, state legislators should take steps to make Washington’s tax structure more fair and sustainable: closing the loophole on capital gains, increasing the estate tax, and exploring other progressive revenue options. Policies like these will help ensure more of Washington’s wealthiest contribute their fair share to education, health, and other foundations of thriving communities, including:

- Expanding access to affordable childcare and early learning, and improving quality by investing in compensation for the early childhood workforce.

- Expanding access to affordable health care and controlling out-of-pocket costs for individuals and families, by providing a state-sponsored public option with wraparound support in the Exchange.

- Ensuring high school graduates and those seeking new job skills with access to public higher educational opportunities – without crippling educational debt.

- Providing new mechanisms for retirement savings and establishing a system of long-term care insurance.

- Addressing the need for affordable housing in communities across the state.

- Providing flexible transportation options, in both urban and rural settings, so people can easily get to jobs and services and commerce can thrive.

These public policies will help promote sustainable growth, equitable opportunity and economic stability through life’s inevitable ups and downs – helping build an economy where every person has the individual freedom and equality of opportunity to follow their own path to happiness, and all people, families and communities can flourish.

Footnotes

[1] Based on EOI analysis of Washington State Employment Security Department data from 1) Employment Estimates (WA-QB, not seasonally adjusted) through August 2018, and 2) Covered Employment (QCEW) through 2018 Q1. Wages expressed in 2018 dollars using CPI-U-RS. 2018 wages are annualized average of seasonally adjusted Q1 wages. 2018 Retail Trade (less Nonstore retailers) and Nonstore retailers employment data is estimated based on 2017 data; wages are through 2017 Q4, inflation-adjusted to 2018.

[2] Based on EOI analysis of Washington State Employment Security Department data from 1) Employment Estimates (WA-QB, not seasonally adjusted) through August 2018, and 2) Covered Employment (QCEW) through 2018 Q1. Wages expressed in 2018 dollars using CPI-U-RS. 2018 wages are annualized average of seasonally adjusted Q1 wages.

[3] “Wages” include only hourly or salaried remuneration to employees.

[4] “Compensation” includes wage and salary disbursements, as well as supplements such as employer contributions for employee retirement plans, health coverage and social insurance. Note that to the extent that increased costs for health coverage represents only inflation, it is not an added benefit for employees, though it is included in measures of compensation.

[5] Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Real GDP by state, All industry total. Economic Policy Institute analysis of unpublished total economy data from Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Productivity and costs program; employment data from Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics; wage data from the Current Population Survey and compensation data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, State/National Income and Product Accounts public data series.

[6] Initiative 688 (approved by Washington voters in 1998) increased the minimum wage and required Washington state to make a yearly cost-of-living adjustment to the minimum wage starting in 2001. Initiative 1433 (approved by Washington voters in 2016) requires a statewide minimum wage of $11.00 in 2017, $11.50 in 2018, $12.00 in 2019, and $13.50 in 2020. Beginning in 2021, the minimum wage will receive a yearly cost-of-living adjustment.

[7] Sommeiller, Estelle, and Mark Price. 2018. The New Gilded Age: Income Inequality in the U.S. by State, Metropolitan Area, and County. Economic Policy Institute, July 2018.

[8] Economic Policy Institute, “Union decline and rising inequality in two charts”, https://www.epi.org/blog/union-decline-rising-inequality-charts/.

[9] Economic Policy Institute, “How today’s unions help working people”, https://www.epi.org/publication/how-todays-unions-help-working-people-giving-workers-the-power-to-improve-their-jobs-and-unrig-the-economy/.

[10] American Community Survey 2017 1-Year Estimates, Sex by Industry and Median Earnings in the Past 12 Months for the Full-Time, Year-Round Civilian Employed Population 16 Years and Over, Washington State.

[11] Based on EOI analysis of U.S. Census Quarterly Workforce Indicators, Full Quarter Employment (Stable) wages and employment; monthly wage calculated as 3-quarter weighted average for 2017 Q1 to 2017 Q3.

[12] Based on Economic Policy Institute analysis of unpublished Total Economy Productivity data from Bureau of Labor Statistics Labor Productivity and Costs program, and Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata.

[13] Based on Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data.

[14] Based on EOI analysis of U.S. Census Quarterly Workforce Indicators, Full Quarter Employment (Stable), second quarter average monthly wages. Inflation adjusted to 2017 dollars using CPI-U-RS.

[15] Economic Policy Institute, “Racial gaps in wages, wealth and more: a quick recap”, https://www.epi.org/blog/racial-gaps-in-wages-wealth-and-more-a-quick-recap/.

[16] For a deeper review and analysis of the racial pay gap, see “Black-white wage gaps expand with rising wage inequality”, Economic Policy Institute, https://www.epi.org/publication/black-white-wage-gaps-expand-with-rising-wage-inequality/.

[17] Sources: Median Family Income: American Community Survey 1-year estimates (Table S1903); Rent: American Community Survey 1-year estimates (Table GTC2514).

[18] Sources: Median Family Income: American Community Survey 1-year estimates (Table S1903); Home prices: Runstand Department of Real Estate, University of Washington. Except for Housing (own), inflation adjusted using CPI-U-RS.

[19] 2017 and 2006 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Travel Time to Work for Workplace Geography (B08603)

[20] Kids Count Data Center, costs for Licensed Care Center and Family Child Care Home, and American Community Survey, Median Income in the Past 12 Months (S1903). Inflation-adjusted using CPI-U-RS.

[21] EOI estimate based on actual enrollments to date, “Higher Education FTE Student Enrollment History by Academic Year”, accessed 6/27/18: http://fiscal.wa.gov/Workloads.pdf.

[22] Oxfam America, “The Best and Worst States to Work in America,” August 30, 2018, https://policy-practice.oxfamamerica.org/work/poverty-in-the-us/best-states-to-work/.

- Leave a Reply

More To Read

January 6, 2025

Initiative Measure 1 offers proven policies to fix Burien’s flawed minimum wage law

The city's current minimum wage ordinance gives with one hand while taking back with the other — but Initiative Measure 1 would fix that

September 24, 2024

Oregon and Washington: Different Tax Codes and Very Different Ballot Fights about Taxes this November

Structural differences in Oregon and Washington’s tax codes create the backdrop for very different conversations about taxes and fairness this fall

September 6, 2024

Tax loopholes for big tech are costing Washington families

Subsidies for big corporations in our tax code come at a cost for college students and their families

Karla

Fabulous compilation and presentation of data.

Feb 13 2020 at 6:06 PM