The Great Recession took a massive toll on the state’s job market. Today, more than a decade after the onset of the Great Recession, statewide unemployment in Washington is finally below pre-recession levels. But the state unemployment rate is just one way of looking at employment. Let’s dig in to explore a little deeper.

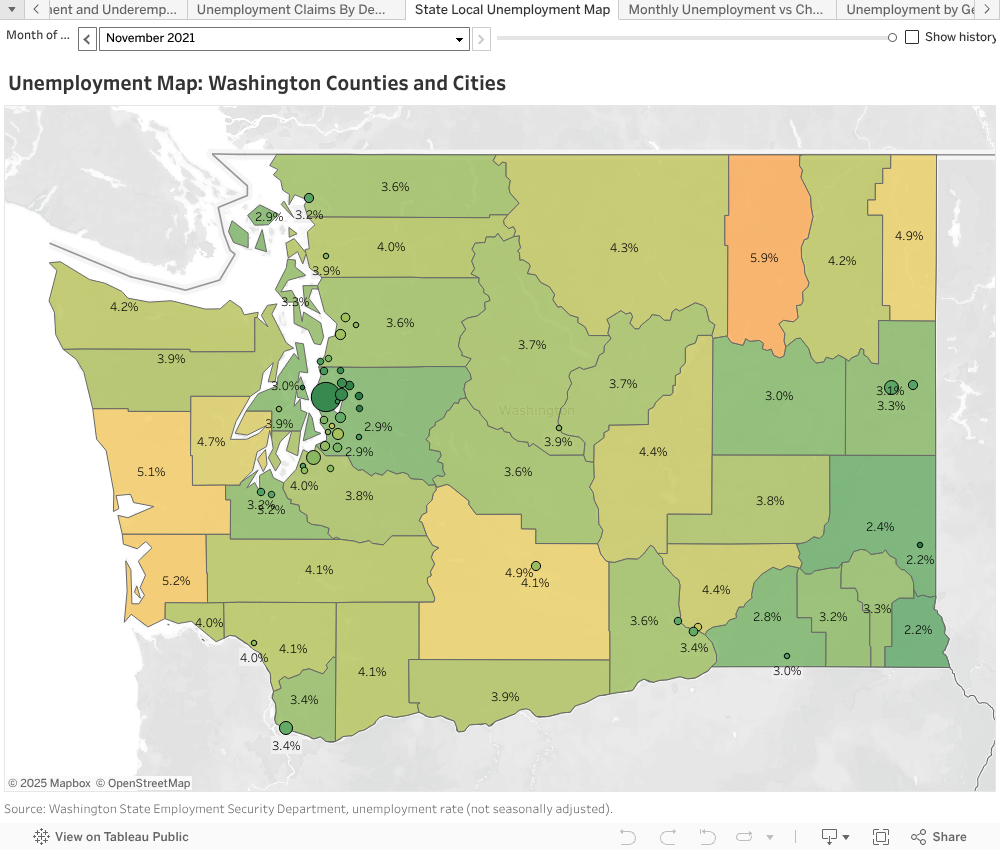

In seven of Washington’s eight largest metro areas (measured by size of labor force), unemployment has been below 5.5 percent since July 2017 — and in the only exception, Yakima, unemployment is lower than at any time in the past 20+ years.

However, in many parts of the state — counties and cities in rural areas, on the Olympic Peninsula and along the Pacific coast — there’s still quite some distance to full employment.

Washington’s civilian non-institutional population, which includes everyone who could — in theory at least — be working in a private or public sector job, is 6.0 million. Of them, as of July 2019, 62.1 percent (~3.75 million) were employed, 4.5 percent (~177,000) were unemployed, and 34.9 percent (~2.1 million) were not in the labor force.

There are many good reasons why someone who *could* be working doesn’t have a job. That’s why the official unemployment rate (called the U-3) counts only those people without jobs who: a) want to work, b) are available to work, and c) have actively looked for work within the past four weeks. This a sensible approach: there are some people whom you wouldn’t want to define as unemployed, even though they aren’t working — like full-time students, a parent who wants to stay at home with a newborn, etc.

However, this way of counting the unemployed also has some limitations: it excludes people who would actually like to have a job, but who haven’t been looking for one reason or another — and those would work more hours, but aren’t getting them. This is sometimes called “slack” in the job market, and it’s another way to tell how well, or poorly, the job market is performing.

One way to measure slack is the underemployment rate (called the U-6). It includes everyone counted in the unemployment rate, plus: discouraged workers (who have stopped looking for work due to current economic conditions); marginally attached workers (who would like and are able to work, but have not looked for work recently); and involuntary part-time workers (employed less than 35 hours/week but want and are available for full-time work).

The state’s underemployment rate is now lower than pre-Great Recession – in fact, lowest ever given data available since 1994. (Note that 2019 rate is 3rd quarter of 2018 through 2nd quarter of 2019; previous rates are expressed as yearly average). But it took an additional year for underemployment to recover to pre-recession levels, compared to unemployment. And since the two rates move in tandem, those areas in Washington facing high unemployment today likely have even higher rates of underemployment.

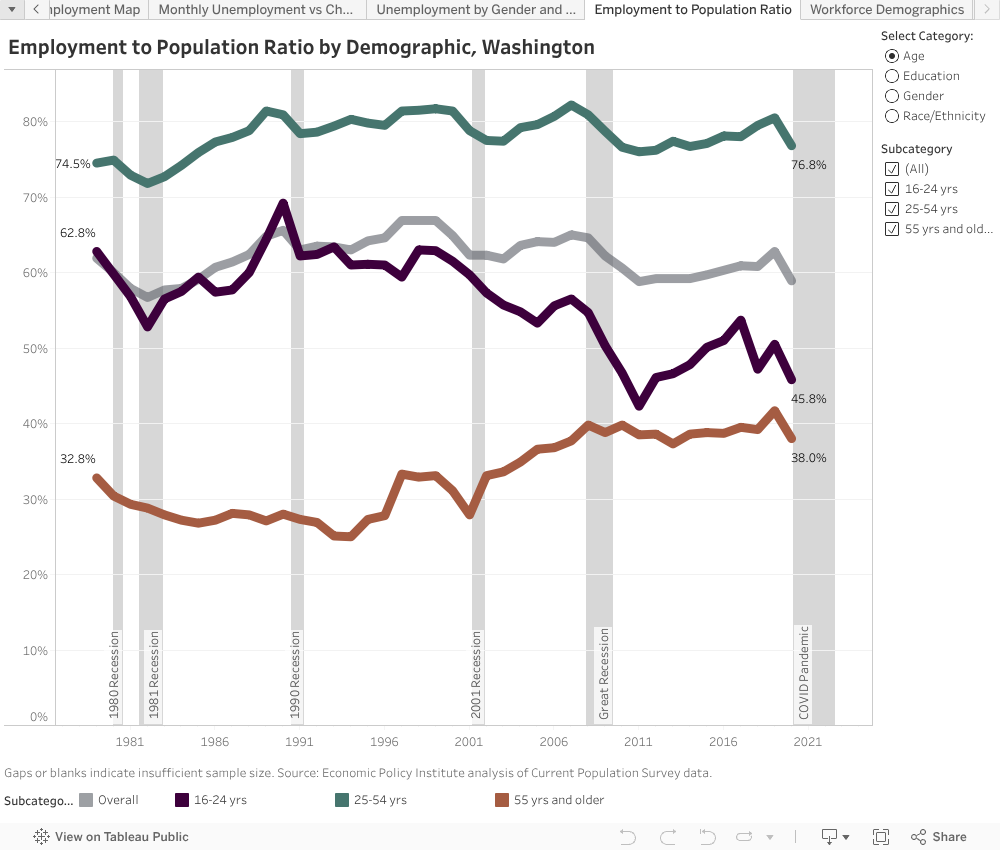

Another way to measure slack is the working-age employment rate, or as economists call it, the “prime-age employment to population ratio”. It’s the percentage of people age 25 to 54 (i.e., those adults you’d typically expect to be in the “working” stage of their lives) who have a job. We wouldn’t expect everyone in this group to be employed, but certainly a high percentage of them.

Case in point: Washington’s working-age employment rate peaked at 82.2 percent prior to the Great Recession. But as of 2018, 79.5 percent of Washington’s prime-age workers are employed. The 2.7 percent difference may not seem like much, but it equates to about 80,000 people who (if previous economic recoveries are any indication) should have jobs by now.

What accounts for the gap? One possibility is the high costs facing many households for things like childcare, long(er) commutes, and deductibles for employer health plans. If a job doesn’t pay well enough to keep up with those costs — and many of Washington’s largest employment sectors haven’t shown strong wage growth — it doesn’t make sense for a person to take that position.

Conversely, if one spouse is lucky enough to have a very high-wage job — like in the information sector, where typical wages are $133,000 above average — the other spouse can likely devote their time something besides a full-time job.

So: is unemployment in Washington as low as it looks to be? Strictly speaking, yes. But looking at local differences, as well as statewide underemployment and working-age employment rates, there is definitely still room for improvement.

More To Read

October 14, 2025

Opportunity for many is out of reach

New data shows racial earnings gap worsens in Washington

January 17, 2025

A look into the Department of Revenue’s Wealth Tax Study

A wealth tax can be reasonably and effectively implemented in Washington state

January 6, 2025

Initiative Measure 1 offers proven policies to fix Burien’s flawed minimum wage law

The city's current minimum wage ordinance gives with one hand while taking back with the other — but Initiative Measure 1 would fix that