Garment workers on strike via the Library of Congress

One of the most valuable elements of the labor movement has been its ability to close numerous wage gaps. Union membership is one proven way for marginalized groups – women, members of the LGBTQ community, BIPOC folks, and immigrants, to name a few – to achieve wages that are on par with those of white men.

This hasn’t always been the case, though. In the early years of the labor movement, many unions were exclusive and segregated, limiting their membership – even when the industries they represented were much more diverse. That exclusion kept them from reaching their own goals and meeting the needs of the broader working community. In fact, it was diversity within labor unions that ultimately made them strong.

One example is the massive organizing effort in New York City at the turn of the 20th century. In an explosive demonstration of strength and solidarity, women – mostly immigrants – proved that there really was strength in numbers; they could be not only an asset, but a necessity to gaining basic rights in the workplace.

Immigrants: They Got The Job Done

Clara Lemlich via the Library of Congress

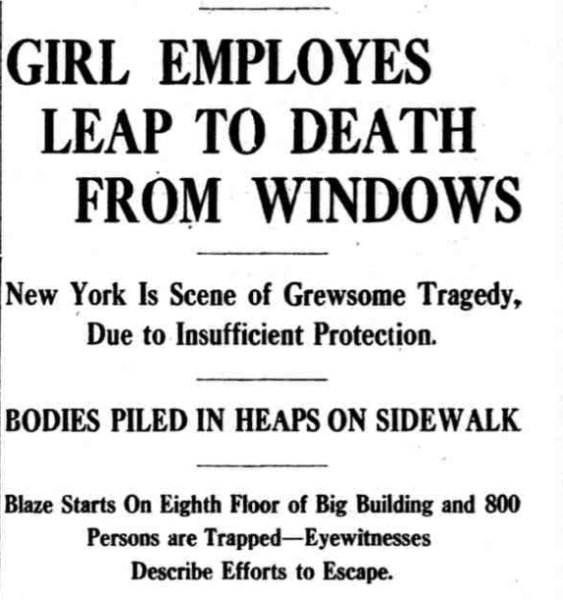

Most people have some knowledge of the tragic 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. If nothing else, they know that the blaze itself was deadly and avoidable and that workers rose up in the wake to demand basic safety regulations (like doors that could actually open).

What fewer people know, though, is that several years before the fire, a teenage girl had begun organizing workers in that very factory to demand safer working conditions. And it was due to her years of agitating that when the fire broke out and took the lives of more than 140 individuals, mostly women and girls, the garment workers were prepared to fight back.

Clara Lemlich and her family had immigrated to the United States several years prior to the deadly disaster. Like many Jewish families, they had come seeking political asylum and spoke exclusively Yiddish. Upon arrival, all of the children were expected to work – and most of the jobs available to immigrant women were in the garment industry. Lemlich, alongside other school-aged girls, worked 11-hour days in a sweatshop, sewing shirtwaists (a fashionable blouse), trendy jackets, beaded bags, and other items they could never afford. After just a few weeks of hard labor, the then-17-year-old could sit idly no more.

Sweatshops – a collective term for cramped spaces of assembly and manufacturing, usually of clothes – were truly awful places to work. With few, if any, windows, negligible light, makeshift seating, and as many human bodies crammed into a space as possible, they were an assault to the senses. Sweatshop owners tended to be wealthy garment industry magnates. They had a vested financial interest in making as many pieces as possible. This industrial approach to clothing was relatively new, and the idea that middle-class women could mail-order or purchase garments that were churned out in a factory-like setting was a popular one.

Industrialization meant clothing was cheaper and more accessible – but it required a lot of human capital. The sweatshop workforce was comprised of folks on the margins. Recently-emancipated individuals from the South, new immigrants, single mothers, and senior citizens often struggled to find work and would toil for very low wages. These workers were squeezed into small spaces, kept for for more than half the day, and barred from any on-the-job activities which might slow them down, like using the restroom or eating a meal.

Unfortunately, the union that represented sweatshop workers didn’t offer much protection. The ironically-named, male-only International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) (the title meant that the workers made ladies garments, not that the workers were, themselves, women) didn’t permit women to engage in bargaining or collective action.

The Ladies Garment Workers Union Says No Girls Allowed

Across the industry, the majority of garment workers were those who weren’t represented by the union. They were overwhelmingly immigrants and most were younger women. Women and girls kept the dangerous machines humming at all hours, often while being harassed and even assaulted by male foreman. They took work home with them, sewing over kitchen tables and in hallways in the dark of night. Many of the “girls” on the machines and the assembly and cutting lines were viewed as “unskilled,” even though their skill-set was just as precise as the “skilled” workers.

The division of “skilled” versus “unskilled” varied by factory – but it almost always served as a way to promote some workers over others. And even though all of the workers suffered through the same conditions – fetid air, eye-straining darkness, and no breaks – the ILGWU’s conservative leadership prioritized what they considered “skilled” workers when they spoke to lawmakers and bosses. These “skilled” workers, the ones who were permitted to organize and lobby, were typically white men who spoke English and knew how to operate and work on the machines. In the union meetings, these members would plead with factory bosses for small changes, but rarely sought larger interventions. Instead, they would wring their hands at wealthy sweatshop owners and local public officials to make small, enforceable improvements – and even those demands would go unanswered.

Clara Lemlich knew that the real change couldn’t come from a handful of men smoking cigars in the back room of a pub. Instead, she wanted to emphasize the sheer volume of people being hurt by the sweatshop system. She had seen the ways that the structure of the sweatshop economy incentivized parents who to keep their kids out of school only to result in premature injuries. It recruited new Americans only to offer no protections against very real outcomes, including disease and death. It chewed workers up and spat them out, treating them as disposable cogs.

She spent years learning about the ways the union operated and organizing the women and girls she worked alongside. If there was going to be a real shift in the way garment workers were treated (not to mention paid), the action was going to have to include everyone, not just the workers who looked and talked like the bosses.

Group of mainly female shirtwaist workers on strike, in a room, New York via the Library of Congress

The Uprising of 20,000

Lemlich at first tried to join the existing union, but was turned away. Undeterred, she began talking with the girls from her own sweatshop, as well as many others that were crammed into apartment buildings, tenements, and old factory buildings. She spoke with fellow immigrants to find out what they would like to see changed. Relatively basic rights – like access to a bathroom and fresh air – and higher wages were the bulk of the responses. Whereas the union leadership had never courted these working-class women and girls, Lemlich went to them directly and created an advocacy network across New York City.

Her recruits, who had also been barred from organizing and physically drained from terrible working conditions, began showing up to the same protests as the men. It was rare for women to protest, let alone to protest with the men in their industry. Their presence – which was not exactly meek or mild – often resulted in threats and even physical violence by both police and union members. But Lemlich was a charismatic girl who brought large numbers of workers – enough to make factory bosses pay attention and to demonstrate the importance of women in community action.

She was just 23 years old when, in 1909, she climbed onto an apple box and declared a general strike, sparking a movement that would ultimately be known as the Uprising of 20,000. For months, thousand of her fellow workers picketed various sweatshops throughout Manhattan – including the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory – demanding basic safety regulations and human rights. The news of their movement hit the papers in other cities, spreading strikes across the nation.

The women’s disruptive, aggressive approach was out of step with the backroom dealing of the ILGWU – in part because they knew that there was an urgency to their work. The working conditions were dire and no small tweaks would fix a culture that used young women “like machines,” Lemlich stated. Rather than negotiating for incremental change to a broken, abusive system, Lemlich and her cohorts took to the streets and, in the 1909 General Strike, tens of thousands of young women were in the streets, refusing to stay quiet about what they’d endured.

This massive organizing effort received more attention – and enrollment – than the union had experienced since its founding. This membership increase meant visibility, but it also meant union dues. The newspapers took notice, as did wealthy benefactors who were more than willing to contribute to the effort.

It became clear to the men of the Ladies Garment Workers Union that they couldn’t keep women out any longer – they were having a hard time recruiting and were basically out of money. After Lemlich and thousands of other novice organizers showed up in huge numbers, they were permitted to join and work together with the union. But, as one writer noted at the time, the “bitterest part of the fight is yet to come.”

The Bitterest Part of the Fight

More women joined the union – but the slower-paced negotiation tactics persisted. The men in charge didn’t take the women’s demands seriously – their calls for improved factory conditions weren’t considered a union priority. Instead, reporting hazards was one of the main tasks – but those reports effected little change. It was the laws and economic system that were the problem, not a few bad actors. .

Lemlich and her fellow organizers continued to picket, despite clear danger. They were brutally assaulted, suffering broken bones, frostbite, and blacklisting from the industry they were fighting to improve. They faced blacklisting, essentially ensuring they would never be able to earn a living again. And yet, many factories remained ruthlessly unsafe. Meanwhile, factory foremen continued to cram as many workers as they could onto each floor, leading to high temperatures and poor air quality. It was common practice to lock the factory doors from the outside to ensure that workers couldn’t leave. And, because many of the workers were living on the margins and felt they had no choice but to work, the spinning bobbins never fully came to a stop, meaning the bosses were never entirely pressed to change their ways.

The picket line was dangerous – but the sweatshops were deadly. When the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory burned – just two months after workers picketed over unsafe working conditions – the country could no longer ignore the harsh reality of sweatshop labor.

The very public, very visible death of more than 140 individuals – the bodies of dozens of immigrant women and many children were laid out on the street for all to see – was a wake-up call to the powers that be, both within the local government and the major labor unions that had failed to advance the demands of the young women who had been striking for years.

Unions learn to UNITE HERE

The 1911 Triangle fire was a turning point for lawmakers and the ILGWU, who saw that incremental change was no longer an option. As the President of ILGWU stated in a 1961 anniversary address, the victims of the fire “were our martyrs because what we couldn’t accomplish by reasoning with the bosses, by pleading with the bosses, by arguing with the bosses, they accomplished with their deaths.”

Instead of working with factory bosses and asking for small changes – like windows that opened – the union and its members began demanding a total overhaul of the sweatshop system.

This complete restructuring would require cooperation – and action – from both lawmakers and industry owners. The people who owned department stores and clothing shops would all need to become familiar with the actual cost of making these garments, both human and economic.

By this time, the leadership had changed, as well. ILGWU was now largely female-run and its ranks were mostly Jewish and Italian immigrants. It became not only a lobbying organization, but an educational powerhouse, informing workers across the country of their rights and sharing organizing tactics and strategies. They developed political power and worked with reformers well into the days of the New Deal – including adding thousands of Black women to their membership following the first World War. In its modern iteration, ILGWU – which is now part of the Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees (UNITE) Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union (HERE) – is one of the nation’s largest and most powerful unions, boasting 300,000 active members in the garment, hotel, and food service industries.

Sexism and Greed: A Lethal Combination

The Triangle Shirtwaist disaster was a predictable, preventable tragedy. But thanks to corporate greed, sexism, xenophobia, anti-Semitism, and a lack of government oversight, it was one that organizers were unable to prevent. Prejudice both within and outside of the union kept the organization from becoming as strong and as powerful as it might have been. Disregard for the well-being of women, immigrants, and children kept the state and local government from passing legislation to protect them. A desire to make money kept the bosses from putting aside cost-saving measures in order to keep the workers safe and healthy. The union leadership’s initial unwillingness to incorporate new kinds of ideas and tactics delayed necessary changes until it was too late for the hundreds who died in the Triangle disaster.

The union leadership of ILGWU may or may not have eventually decided independently to include a broader membership – but there would doubtlessly have been more fatalities in the meantime. It took women like Clara Lemlich and her colleagues to demand a role in the organization and demonstrate the power and necessity of inclusion and diversity.

Today’s unions – just like all institutions built in a nation rooted in colonialism – are still actively working toward active anti-racism, both in their practices and in their representation. But the emphasis on truly collective action which benefits all members has been instrumental in creating a labor movement for everyone. And we see the results; whereas nonunion workplaces struggle to close racial and gender equity gaps, organized labor continues to make work safer, more equitable, and more inclusive.

More To Read

January 17, 2024

Which costs more: Shoplifting or wage theft? The answer might surprise you

Wage theft continues to rob workers — but Washington is stepping up

May 1, 2023

Before the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, Women Tried To Warn the Unions

How a teenage immigrant helped build one of the most powerful labor unions in the United States

March 10, 2022

Equal Pay Day 2022: Work Still Remains to Advance Gender Equity

Women’s history month and Equal Pay Day give us the opportunity to celebrate progress, and acknowledge the collective work we have ahead.