![[Black and white, an informal portrait of a young Black woman surrounded by laundry in Newport, R.I.]](https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/LOCSnip-600x575.png)

An “informal portrait” of a young Black woman doing laundry. 1903, from the Library of Congress

Sims is an example of women’s history in real time – and, very critically, she’s part of a long, proud history of women, specifically women of color, making huge strides in labor. Our industries are still facing glaring gaps in wage and opportunity, but many of the rights and protections women have achieved in the last century are due to the tireless work of marginalized individuals and groups within the labor movement who did not allow themselves to be ignored or left out.

That’s why, this Women’s History Month, we’re celebrating the labor leaders of today and honoring the legacy of women who risked their health, their safety, and their security to demand more for the next generation.

Labor History is Women’s History

Finding any kind of parity in the workplace has always been a challenge – that’s just part of the construction of a patriarchal society. The distinction of “women’s work” is deeply rooted – and it speaks to the devaluing of the labor of women in general. The labor that women have historically practiced, or expected to practice, in the United States was viewed as less important, less challenging, or less culturally significant – in spite of the fact that necessary tasks, like laundry and cooking, are absolutely paramount to the families and communities.

Additionally, women have typically required more flexibility in the workplace, as they have also been disproportionately tasked with care work at home; one report about labor distribution during the COVID-19 pandemic stated that “mothers working full-time spend 50% more time each day caring for children than fathers working full-time.”

As a result, women (and women of color in particular, often face latent discrimination within the industries they frequently populate, which can depress wages, reduce access to benefits (think contract work and even today’s “hustle culture”), and generally reduce lifetime earnings. This earning gap was only worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic, a time when women, who are disproportionately represented in lower-wage care and service work, bore the brunt of the disruption, not to mention the risk.

The systems that allow for entire portions of the population to be undercut and underpaid are difficult to disrupt due to the scope of the problem. But once recognized, they can be dismantled with collective action. Unions, then, have been an essential tool to combating systemic gender-based wage suppression.

It’s no surprise that the labor movement has been a place where women could find footing. What is surprising, or perhaps not, is how little most of us know about the numerous uprisings, protests, and strikes that live at the intersection of women’s history and labor history. Times when women walked out, decided to picket, and were subjected to violence. From the Washerwomen of Jackson, Mississippi to Dolores Huerta’s leadership in the uprising of Latine agricultural workers, women have played an integral role shaping labor history in the United States – even if our celebrations of labor, rights, and the working class don’t often incorporate them.

Looking at several specific moments in history when women recognized the ways in which they were receiving subpar treatment, subminimum wages, and subhuman working conditions, we can see the role of women in labor – and not just on their own behalf. When women have risen up to demand more, they have improved working conditions, compensation, and expectations for everyone.

“We…desire to be able to live comfortably if possible from the fruits of our labor”

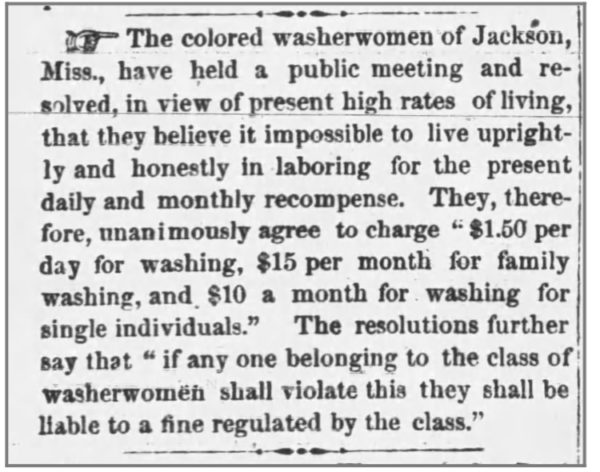

When newly-emancipated Black women in the American South began working for wages, they quickly realized that they would need some kind of protections to ensure fair pay and conditions; they wrote in a statement that they found it “impossible to live uprightly and honestly in laboring for the present daily and monthly recompense.”

It was already a departure for their work to be compensated at all, and in order to avoid a race to the bottom of pricing, these independent contractors – cooks, housekeepers, and other domestic laborers – needed to organize.

In 1866, the Washerwomen of Jackson was born in Mississippi – the state’s first labor union – was founded. That same year, they sent a letter to the Mayor of Jackson, which read, in part:

Be it resolved by the washerwomen of this city and county, that on and after the foregoing date, we join in charging a uniform rate for our labor, that rate being an advance over the original price by the month or day the statement of said price to be made public by printing the same, and any one belonging to the class of washerwomen, violating this, shall be liable to a fine regulated by the class. We do not wish in the least to charge exorbitant prices, but desire to be able to live comfortably if possible from the fruits of our labor.

Unsurprisingly, the landowners and those who were deeply entrenched in the pre-Emancipation economy were unhappy about this show of unity and organization. The kidnapping and subsequent enslavement of African and Caribbean people had not only devalued labor within the market, it had necessarily devalued human beings, stripping them of their humanity. After the official dissolution of the plantation economy, it was unclear how necessary work would be done and who would do it – but many of those who had benefited from the free labor of enslaved individuals were thoroughly rooted in the idea of white supremacy. Returning Civil War generals and other wealthy members of the upper class established “Black codes,” designed to bar freed Black folks from taking on work. People who violated these rules were often beaten or murdered. The notion of paying Black people – let alone Black women – for any kind of work flew in the face of the life that Southern landowners had enjoyed for years and had hoped to cling to after the war.

Reconstruction forces deployed from the North – brigades sent into Southern towns to literally mandate that they comply with Lincoln’s Emancipation order – combined with the devastation of the Civil War which also took its toll on the number of white people available to do work, especially manual and household labor, put the wealthy (and bigoted) in a bind – how could they get their laundry done for a low price? The Washerwomen, then, served as a harbinger of what the Reconstruction South might include – and while many white people didn’t want that at all, all they could do about it was complain loudly. One paper in Alabama denied their statement and concluded that the rates they proposed were “exorbitant,” though it seems unlikely that the editors would have been willing to starch their own shirts for any less.

This collective action was novel for a number of reasons. Through a modern lens, the group of organizers themselves might seem notable. Unlike later labor unions in industries and trades dominated by men, it centered Black women because it was led by Black women. Indeed, despite their inventive strategy for commanding fair prices, for more than a century after this first step, Black women would be kept from labor unions, either implicitly or explicitly.

However, focusing on their race and gender can serve to undermine the action itself – price fixing by working in this manner wasn’t common, especially for “household” services, like cleaning, cooking, and laundry. In the wake of Emancipation, it would have been easy for workers to low-ball one another, agreeing to work for less and less money in an attempt to secure regular clients. But this would have ultimately led to those with the means to pay for labor, not those doing the work, to set the price. And the Washerwomen simply did not allow that to happen. In taking this step at such a critical time of the Southern economy, they were able to draw a line in the sand – a line that would need to be re-drawn many, many more times.

This isn’t to say unions weren’t in existence; that same year in Baltimore, coachmakers were trying to establish the country’s first national organizing body and the eight-hour workweek was on the eve of being codified. But in the South, where the entire economy had been upended and a powerful maelstrom of race, labor, money, and power was brewing, daring to demand a fair price for services was potentially dangerous and definitely necessary. Decades later, the scholar W.E.B. DuBois would criticize the deeply segregated labor unions, while noting that the benefit was extended to all workers, regardless of race.

“Collective bargaining has, undoubtedly, raised modern labor from something like chattel slavery to the threshold of industrial freedom, and in this advance of labor white and black have shared,” he wrote.

Their action also directly confronted assumptions about Black women and their role in the economy. By actively demanding a fair price for their work – and working together to ensure that these prices would be uniformly set across the city – the Washerwomen were able to not only demonstrate their worth and power, but also set the stage for tradesmen, like longshoremen in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1867, and, another group of laundry workers in Atlanta in 1881, to do the same.

As the Southern states exited the practice of enslavement of humans and the expectation of free labor, this early demonstration of strength was critical in setting the tone as the workforce entered a new era. Unfortunately, Reconstruction was overwhelmingly unpopular among white people who raged against the new rights and freedoms that their Black neighbors were now expressing. As a result, many Black folks began moving to the North – and, within a generation, would be represented by some of the most active labor unions in the country.

Women’s Work, Everyone’s Benefit

The story of the Washerwomen of Jackson would portend things to come in the American economy – and elements of their struggle are still visible in our modern economy. This is why the study of women’s history – all of women’s history – remains relevant.

In her important book, Counting for Nothing, New Zealand scholar and former elected official Marilyn Waring details the ways in which the tools of global economic assessments omit the impact of women’s work – and, specifically, how “women’s work” is viewed through an economic lens only when it is performed by governmental bodies, but not when performed in the home or the workplace by individual women. Pointing out the work of the welfare system, she mentions caretakers in hospitals, schools, and incarceration settings. That work is labor, it’s paid, it’s of economic impact.

“But a mother, daily engaged in these unpaid activities, is ‘just a housewife.’”

To this day, the struggle for living wages in the domestic, care, and service industries remains. Consider the uphill battle that raising the minimum wage – a policy which would overwhelmingly benefit women and people of color – has fought for more than a decade, when $15 was considered absurdly high. Opponents used similar rhetorical tactics to the op-ed writers in the Reconstruction South by decrying the worth of the work (and thus, the worth of the workers) without recognizing the community-wide benefit of paying workers enough money to survive. Much as the Washerwomen were panned for demanding “exorbitant” wages, when nurses – hailed as “heroes” during the COVID-19 pandemic – have been denied basic cost-of-living and safety policies that would make their work more tenable.

In spite of more than 150 years of dogged work performed by women in the United States today, one of the most significant sources of the gender pay gap remains the historical distinction of “women’s work.” Industries including education, care, and tipped work are disproportionately filled with women of color. According to the Department of Labor’s blog, “of the portion of the wage gap that can be explained, by far the biggest factor is the types of jobs that women are more likely to have than men; and these are jobs that tend to pay less.”

“This industry and occupational segregation – wherein women are overrepresented in certain jobs and industries and underrepresented in others – leads to lower pay for women and contributes to the wage gap for several interrelated reasons,” they wrote in 2022.

And yet, even these enormous barriers to financial stability represent a kind of progress for women in the workplace. A century ago, that same “women’s work” was often completely uncompensated. Prior to the Equal Pay Act of 1963, gender discrimination in pay was completely legal. The following year, the Civil Rights Act expanded those protections to people regardless of race or nationality. Both of these laws were passed following decades of organizing by marginalized groups – they are the direct result of political pressure and public outcry.

Long before these important pieces of legislation, though, most of the strides made by women in the workplace happened in union meetings, not Congressional hearings. Women like the Washerwomen of Jackson and those we’ll cover in future blog posts put their futures, their bodies, and safety on the line to create protections where none existed. And in doing so, they not only created safer and more equitable workplaces for themselves, they built structures of safety and equity for all workers.

More To Read

March 24, 2023

Women’s Labor is Women’s History

To understand women's history, we must learn the role of women - and especially women of color - in the labor movement

March 17, 2020

Everyday Heroes in the COVID-19 Pandemic

We as a society can get come out of this stronger on the other side