This summer, I joined representatives from AARP Washington and the Washington State Labor Council for a retirement security listening tour organized by Washington State Treasurer Mike Pellicciotti. While the sessions were held in five very different communities (Tukwila, Port Angeles, Yakima, Everett, and Steilacoom), many of the comments and conversations were strikingly similar.

One common theme was the high cost of basic needs – like housing, health care, and childcare – and the difficulty of saving for retirement when you’re not earning enough to make ends meet or having to take a second or third job to get enough work hours. Employers and business owners in attendance remarked that plan costs and complexity are barriers for them. And everyone recognized that current retirement policies (federal, state, and private) aren’t doing enough.

The State of Retirement in Washington State

National and local data back up those experiences. Many low- and moderate-income families in Washington do not have sufficient earnings to meet their daily expenses, much less save for retirement. For example: in 11 of Washington’s 20 largest counties, a family of four earning 90% of median family income has less than 5% of their income remaining after expenses.[i]

Among the bottom 25% of wage-earners nationally, less than half have access to a retirement savings plan at work – and less than one-quarter participate. In the second quartile (the 25th to 50th percentile), 60% have access to a workplace retirement plan, but less than half participate.[ii]

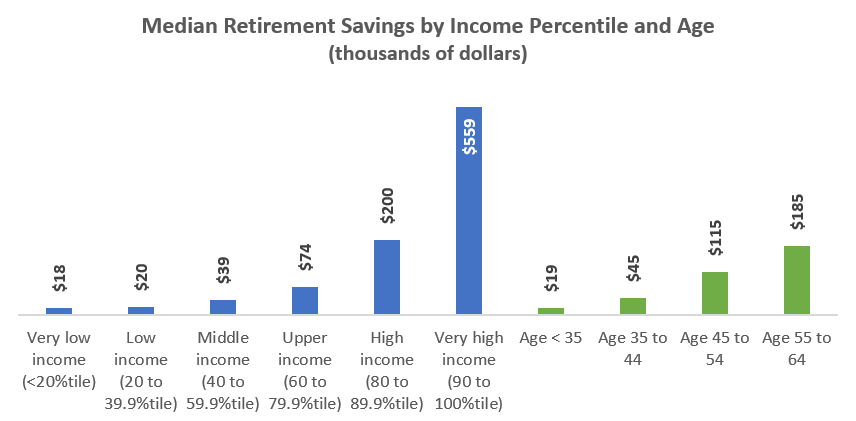

Given that, it’s hardly surprising people aren’t able to easily save for retirement. Middle-income Americans have median retirement savings of just $39,000.[iii] Among all those nearing retirement age (55 to 64), median savings are $185,000 – worth only about $7400/year in retirement.[iv],[v] And the average Social Security retirement benefit for a Washington resident is just $20,474/year.[vi]

Source: Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances 2023

How States Are Responding

To tackle this challenge, legislators in many states have considered or enacted legislation aimed at increasing access to – and by extension, personal savings in – workplace-based retirement plans.

The most common is an automatic IRA, or “Auto IRA” – so called because the state requires businesses that don’t offer a comparable or better retirement plan to automatically enroll their employees in an IRA that is set up for them (often by a firm under contract with the state).

After that, the employer’s role is to forward a portion of the employee’s pay to their IRA – typically 3%-5% to start, with scheduled increases each year up to a defined maximum. Employers are not permitted to contribute to employee accounts. Employees, for their part, can pause, opt-out, or change their contributions (which are typically after-tax) at any time.

Auto-IRA programs are now running in 7 states (with some states running programs in partnership) and have been enacted in 9 others.

Less common (but with other advantages and drawbacks) is an open Multiple Employer Plan, or “Open MEP”, which functions like a public 401k; the state administers the plan, and employers who voluntarily sign up can then provide a 401k for their employees (who choose whether to enroll). Employers can make matching contributions, and employees can make pre-tax contributions.

It’s also possible for states to run a hybrid Open MEP/Auto-IRA program. Massachusetts – the single state currently running an Open MEP – is considering such an approach.[vii]

What Oregon’s Experience Reveals

Oregon was first to enact an Auto-IRA, called “OregonSaves”. The state phased in enrollments starting with larger employers in 2017. Today it requires every employer that does not offer a qualified, employer-sponsored plan to participate. Outcomes so far have been relatively modest:

- A 2021 study found OregonSaves measurably increased employee savings by reducing search costs. While average account balances grew from $375 to $1080 during the study period (August 2018 to June 2021), the program’s actual participation rate was just 34.3%. The most common reason for opting out was “I can’t afford to save at this time.” Researchers noted that “employees opting out…are often doing so for rational reasons.” [viii]

- A 2023 analysis noted the program’s “modest effect on accumulated balance aligns with previous studies” and showed “a 2.5 percentage point (ppt) (12 percent) increase in IRA participation and a 3ppt (3 percent) increase in IRA balances” compared to workers in control states. The increased retirement assets don’t appear to “crowd out” non-retirement savings, and there is a higher probability of participation in IRA plans among females, singles, and those without children under 18 years old. However, the lack of employer matching may make it less appealing to workers.[ix]

Oregon’s experience illustrates how the realities of working life (and the lack of an employer match) limit employee participation and asset accumulation, even if all employers without a qualified, employer-sponsored plan are required to facilitate an Auto-IRA – and that’s before accounting for the longer-term financial risks of a recession or market crash, which are attendant to any equity investment.

But despite those limitations, Oregon’s results show that an Auto-IRA (or hybrid Auto-IRA/Open MEP) in Washington could help more people build some degree of additional financial security.

Considerations for Washington

If state leaders move forward with such a program, there are several important considerations in legislative design and program implementation. Since an Auto-IRA or Open MEP will mostly utilize the savings of low- and moderate-income workers (as their employers are most likely to be covered), the state must take steps to mitigate financial and program risk for participants. For example:

- The Washington State Investment Board (with its strong track record of managing public pensions and other investments) should oversee or ensure a set of pooled and diversified investment portfolios for participants, to provide some protection against market gyrations.

- To avoid stranded or forgotten assets, the state must commit to strong and continued outreach to participants in multiple languages and formats. The program’s website should be easy to remember and forever accessible. Not all participants will be comfortable with or have access to the internet, so they should also receive a yearly statement by mail.

- Participants should be able to easily withdraw their contributions without penalty. It is unreasonable to expect a low- or moderate-income worker to set aside limited savings without being able to access it in an emergency – or simply because they want to. After all, it is their money!

- Program and fund fees must be kept at or below what participants would otherwise pay “off-the-shelf” – because high fees destroy wealth.[x] Today, Vanguard charges account holders $25/year for Roth, Traditional, and Single Participant SEP-IRAs, and $60/year for 403b plans.[xi] Fund fees also continue to decline: in 2022, the average asset-weighted average expense ratio for active funds was 0.59%, and for passive funds was 0.12%.[xii]

- Program startup costs should not be passed onto participants. If state policymakers find it is in the public interest to create an Auto-IRA or Open MEP, then public funds – or a tax on covered employers – should be utilized to get it running.

- To deter potential wage theft by unscrupulous employers, the program must include strong safeguards and oversight, paired with stringent penalties and rigorous enforcement.

- To ensure policymakers, participants, and the public have a clear understanding of what such a program accomplishes over time, annual reporting on outcomes (and publication of anonymized participant and employer data) should be required, so agency staff, academic researchers, and advocates can analyze the results and provide feedback.

We Need Bolder Policy Solutions

Washington faces a crisis of low-income elderly residents in the coming decades: tens of thousands are at risk of living out their years with a diminished quality of life due to insufficient income in retirement – and federal, state, and local governments will feel the budget impacts.

I was encouraged by the conversations I heard in the cities I visited: people recognize that a secure, affordable way to save at work is essential for reliable, sufficient income later in life. But it’s also clear the state needs bolder policy solutions than what is currently on the table.

While Social Security protects against outright poverty, alone it is not enough to retire with a reasonable standard of living and cover the increasing health care and other costs associated with aging. Private, employer-sponsored plans no longer fill the gap between what Social Security provides and what people need to be economically secure – and Auto-IRAs or Open MEPs are only a marginal replacement. Slow growth in wages, rising expenses, increasing student debt, and the risk of losses in market investments compound these problems.

Meeting the Challenge

One way Washington could broadly improve economic security in retirement is through an income supplement for retired workers. Funded by a small payroll tax (paid by both employers and employees, as Washington already does with Paid Family and Medical Leave), it could provide progressive benefits based on an individual’s wage history (which employers already report for state Unemployment Insurance purposes).

Another approach (dovetailing with an Auto-IRA/Open MEP) is to boost the incomes of low-wage workers so they have more financial flexibility to save. Cities could amend local minimum wage ordinances (and Washington its minimum wage law) to require employers that don’t sponsor a retirement plan featuring an employer contribution or match to pay a higher wage to their employees.

And finally, Congress needs to “scrap the cap” on Social Security’s taxable earnings and increase benefits. Today, 94 percent of workers pay Social Security tax on every paycheck – but most of the earnings of the top 1 percent, and especially the top 0.1 percent, escape being taxed because of a cap on taxable earnings (set at $160,200 in 2023).[xiii] By scrapping the cap, federal lawmakers can increase benefits and improve Social Security’s long-term funding outlook.

If there’s a North Star for the state’s retirement policy, I think it’s this: We don’t all plan to spend our retirement the same way, but everyone wants to live out their years with dignity. Washington’s retirement policy success will be measured by the degree to which our choices deliver on that for every resident of our state.

[i] Economic Policy Institute Family Budget Calculator: https://www.epi.org/resources/budget/ and American Community Survey, Median Family Income in Past 12 Months by Family Size, 2022.

[ii] United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022 National Compensation Survey.

[iii] Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances, accessed October 2023, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scf/dataviz/scf/chart/#series:Retirement_Accounts;demographic:inccat;population:1,2,3,4,5,6;units:median;range:1989,2022.

[iv] Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances, accessed October 2023, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scf/dataviz/scf/chart/#series:Retirement_Accounts;demographic:agecl;population:all;units:median;range:1989,2022.

[v] As a rough guide, financial planners recommend withdrawing no more than 4% of one’s retirements savings per year, assuming a 30-year retirement.

[vi] U.S. Social Security Administration, “OASDI Beneficiaries by State and County 2021”, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/oasdi_sc/index.html.

[vii] The Open MEP program in Massachusetts limits employer participation to the non-profit sector, but this was a policy choice – it could be offered more broadly, even to every employer doing business in a state. Missouri has also recently enacted an Open MEP, while Vermont has moved from an MEP to an Auto-IRA.

[viii] Chalmers et al, “Auto-Enrollment Retirement Plans in OregonSaves”, 2021, https://mrdrc.isr.umich.edu/pubs/auto-enrollment-retirement-plans-in-oregonsaves-2/.

[ix] Dao, Ngoc, “Does a Requirement to Offer Retirement Plans Help Low-Income Workers Save for Retirement? Early Evidence from the OregonSaves Program”, August 1, 2023, https://ssrn.com/abstract=4561558.

[x] Saving $1200/year for 30 years at a 7.5% rate of return yields ~$111,600 with a 1% annual fee, but ~$129,600 with a 0.2% fee – a difference of $18,000.

[xi] “Vanguard annual account service fees”, accessed October 2023, https://investor.vanguard.com/client-benefits/account-fees.

[xii] “Morningstar Finds Investors Saved Nearly $9.8 Billion In Fund Fees In 2022”, accessed October 2023, https://newsroom.morningstar.com/newsroom/news-archive/press-release-details/2023/Morningstar-Finds-Investors-Saved-Nearly-9.8-Billion-In-Fund-Fees-In-2022/default.aspx.

[xiii] Set by Congress in 1977 and indexed to average wage growth, the tax cap was intended to cover 90 percent of all wages. But over the past several decades, wage growth for low- and middle-income Americans has slowed, while wages at the top have grown dramatically. As a result, the cap now covers just 81 percent of aggregate wages. See: Economic Policy Institute, “A record share of earnings was not subject to Social Security taxes in 2021”, January 2023, https://www.epi.org/blog/a-record-share-of-earnings-was-not-subject-to-social-security-taxes-in-2021-inequalitys-undermining-of-social-security-has-accelerated/.

More To Read

February 27, 2024

Which Washington Member of Congress is Going After Social Security?

A new proposal has Social Security and Medicare in the crosshairs. Here’s what you can do.

February 27, 2024

Hey Congress: “Scrap the Cap” to strengthen social security for future generations

It's time for everyone to pay the same Social Security tax rate — on all of their income

January 22, 2024

“Washington Saves” legislation won’t solve our retirement security crisis. Lawmakers should pass it anyway.

The details of this auto IRA policy matter.

Lorie Lucky

I think the planning for a state plan has been excellent!! Bravo!!

But I have some concerns…what about state employees who have made less throughout their working lives because of discrimination? For example, there are still women alive who entered the state’s workforce in the 50’s, 60’s, 70’s, and ’80’s – when I entered the state workforce full-time in 1967, Time Magazine reported that, on average, women workers were making 48% of what men made. And we should consider that undoubtedly minority women were in even worse positions vis-a-vis white men. How can the State make sure that people who were intentionally paid less (farmworkers, nursing home workers, fast-food workers, almost all women, etc.) won’t live out their retirements in poverty? Studies have found, time after time, that single/widowed women are more at risk for poverty in retirement than other groups.

Nov 11 2023 at 12:32 PM