When the U.S. women’s national soccer team won equal pay with the men’s team a few weeks ago, it was a big deal – and not just for them. In almost every field, from tech, to health care, teaching, and restaurants, men get paid more than women. Women of Color face a double whammy of gender and race-based stereotypes, harassment, and discrimination.

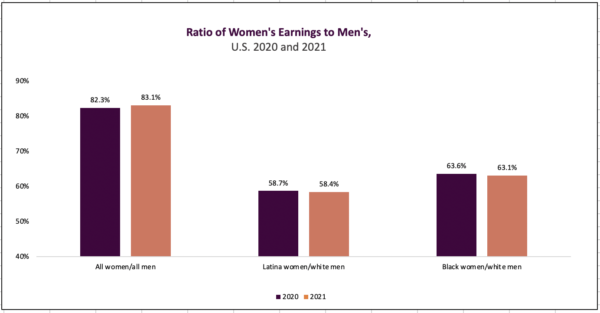

Source: Institute for Women’s Policy Research analysis of Current Population Survey data.

In 2021, according to analysis by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, women in the U.S. who worked fulltime made 83.1% of men’s wages. That figure increased from 81.5% in 2019, but not because of across the board wage gains by all women. Rather, many highly paid professional women were able to continue working from home at full salary during the pandemic, while lower-wage women more often lost work, thus facing real food and housing insecurity. The race + gender wage gap meanwhile got worse over the past year. In 2021, Black women were paid 63.1% of White men’s pay and Latina women just 58.4%.

Here in Washington state, we tend to have an even larger wage gap because we have so many highly paid jobs in male dominated occupations. According to 2019 American Community Survey data, women held just 22% of fulltime computer-related jobs in the state – Washington’s most highly paid major occupation – and their median pay in those jobs was just 78% of men’s. In food service, women held about half of the fulltime jobs and made 92% of men’s typical pay, but wages in those food service are among the lowest of any occupation. Across all job categories, median earnings for women working fulltime were $15,000 less than men’s for the year.

Those lower wages for women mean their kids are more likely to grow up in poverty, especially if they’re single moms, and it’s harder to maintain stable housing and access health care. The wage gap also follows women into retirement. Workplace retirement plans are mostly limited to highly paid employees, and benefits from the nation’s main support system for retirees, Social Security, are based on wages made during working years. In 2019, annual Social Security benefits averaged $13,505 for women over age 65, compared to $17,374 for men.

Lots of compounding issues are reflected in the gender and racial wage gaps, including discrimination and the prevalence of harmful stereotypes. In a recent survey of women in science, 67% of all women and 77% of Black women said they had to show more evidence of competence than men to be taken seriously. Over half, including 61% of Asian women, said they faced a backlash for stereotypically masculine behavior such as assertiveness. 34.5% had experienced sexual assault or harassment, undermining their ability to progress in their careers.

These experiences start limiting the access of women and BIPOC men to STEM education as early as elementary school. Girls often losing confidence in their math ability by 3rd grade. A University of Washington study of undergraduate biology classes found that male students consistently underestimated the knowledge and grades of their female classmates. University faculty hold those same biases. Another study found that science professors were both more likely to hire someone with a male-sounding name for a lab position than an identical applicant with a female-sounding name, and to offer the male a higher starting salary. Representation matters for both women and BIPOC students – in research universities across the country including UW, Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people hold only 4% of postdoctoral and faculty positions in STEM fields.

Discrimination occurs across all types of jobs. In large national food service and retail chains where frontline supervisors typically have extensive discretion over schedules, women of color are more likely than other workers to have shifts canceled or to be given on-call shifts, according to a Harvard study of shift workers. Such schedule instability results in lower earnings, difficulties with child care, greater likelihood of experiencing hunger, and more housing instability.

Discrimination occurs across all types of jobs. In large national food service and retail chains where frontline supervisors typically have extensive discretion over schedules, women of color are more likely than other workers to have shifts canceled or to be given on-call shifts, according to a Harvard study of shift workers. Such schedule instability results in lower earnings, difficulties with child care, greater likelihood of experiencing hunger, and more housing instability.

In most families, women are still responsible for the majority of child care. A major time-use study from 2020 found that employed mothers of children younger than 13 spent on average three more hours every day watching the kids than fathers. Unemployed mothers spent twice as much time as unemployed fathers focused exclusively on childcare.

Inaccessible child care and erratic school closures have kept many women from returning to work as the economy lurches back toward “normal.” Despite recent rosy reports of job growth, there are still 1.2 million fewer women in the U.S. workforce now than at the start of 2020. Even before the pandemic, lack of affordable child care is one of the factors that also pushed women to work part time. In 2019, women held 46% of jobs in Washington, but only 41% of fulltime jobs, according to American Community Survey data. The chronic underfunding of childcare by the state and federal governments results in a primarily female childcare workforce making poverty level wages, women in all fields being pushed out of the workforce, and employers not having full access to potential talent.

Any difficulties finding affordable child care and any disruptions in access – like a worldwide pandemic – both cause real economic hardship in the moment and limit women’s ability to increase their earnings over the long term. Each time women reduce their hours or temporarily step away from work, they lose out on raises and promotions, and often have to start over at the bottom of the wage scale when they return to work.

Individual women trying to educate or negotiate their way into better careers and higher earnings, and encouraging employers to do the right thing will not end the gender/race wage gap.

The equal pay victory of the U.S. women’s national soccer team points to several keys to achieving more comprehensive change. Vocal leaders including Megan Rapinoe, who has stood up both for Black Lives Matter and equal pay, advocated for change for all current and future professional female soccer players, not just a better contract for herself. Team members are also represented by a labor union – and unions help raise wages and reduce gender and racial wage disparities in every field.

Public policies forcing changed behavior are also important. The very existence of professional women’s soccer in the U.S is rooted in the historic passage of Title IX by Congress in 1972. That law, which arose out of the Civil Rights and women’s rights movements of that era, banned sex discrimination in educational programs receiving federal funds, opening access to sports for women and girls in high school and college.

Here in Washington, broad coalitions of community groups and labor unions have mobilized to pass policies that support equity in pay and career opportunities. That includes laws establishing workplace standards that help everyone balance work and caregiving responsibilities, such as Paid Sick Leave, Paid Family and Medical Leave, and strong overtime protections. The Equal Pay and Opportunities Act gives employees rights to discuss pay in the workplace, inquire about job opportunities, and thanks to additional provisions that just passed Washington’s legislature, will soon require employers to post expected pay ranges in job announcements, giving workers a little more power in the negotiation process and shedding light on whether employers are providing equal pay for equal work.

Women’s history month and Equal Pay Day give us the opportunity to celebrate progress, and also to acknowledge the collective work we have ahead.

More To Read

January 17, 2024

Which costs more: Shoplifting or wage theft? The answer might surprise you

Wage theft continues to rob workers — but Washington is stepping up

May 1, 2023

Before the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, Women Tried To Warn the Unions

How a teenage immigrant helped build one of the most powerful labor unions in the United States

March 10, 2022

Equal Pay Day 2022: Work Still Remains to Advance Gender Equity

Women’s history month and Equal Pay Day give us the opportunity to celebrate progress, and acknowledge the collective work we have ahead.