Wages

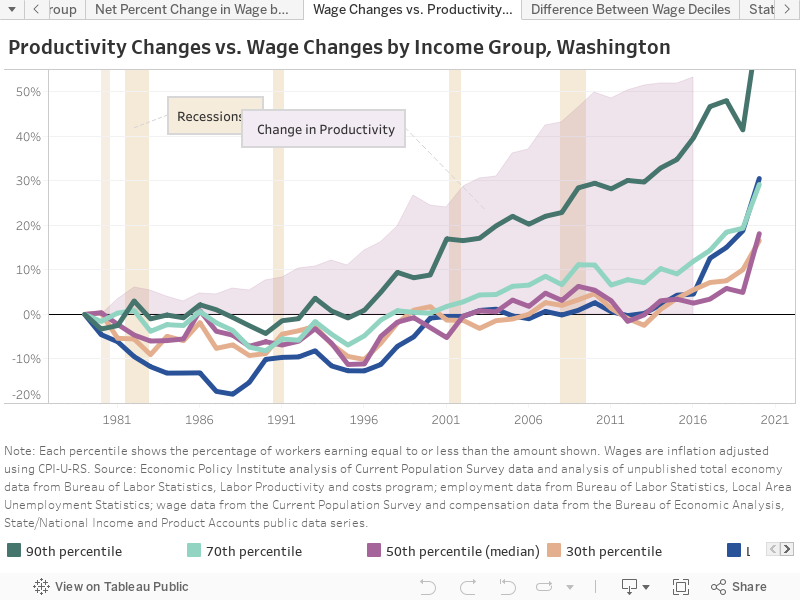

Since 1979, wages for the bottom 60 percent of Washington workers have increased $1/hour — or less! — after adjusting for inflation; meanwhile, the top 10 percent have seen hourly wages jump nearly $18/hour.[1]

It’s not for lack of economic growth: between 1979 and 2016 (date of latest available data), Washington’s economic productivity increased more than 53 percent. But during the same period, median compensation (where 50 percent of wage earners earn less, and 50 percent earn more) grew just 2.6 percent, as the benefits of growth flowed increasingly to the top in the form of higher wages and corporate profits.[2],[3]

One piece of good news: Washington’s minimum wage laws are working as intended. During the 1980’s and 90’s, the lowest-paid 20 percent of workers (who earn less to begin with) saw bigger drops and smaller increases in pay than did those in higher wage brackets. The state’s landmark voter-approved 1998 minimum wage law started to limit those losses, and in 2017 (after another voter-approved minimum wage increase), the lowest-paid 30 percent of workers finally began to make some headway on wages.[4]

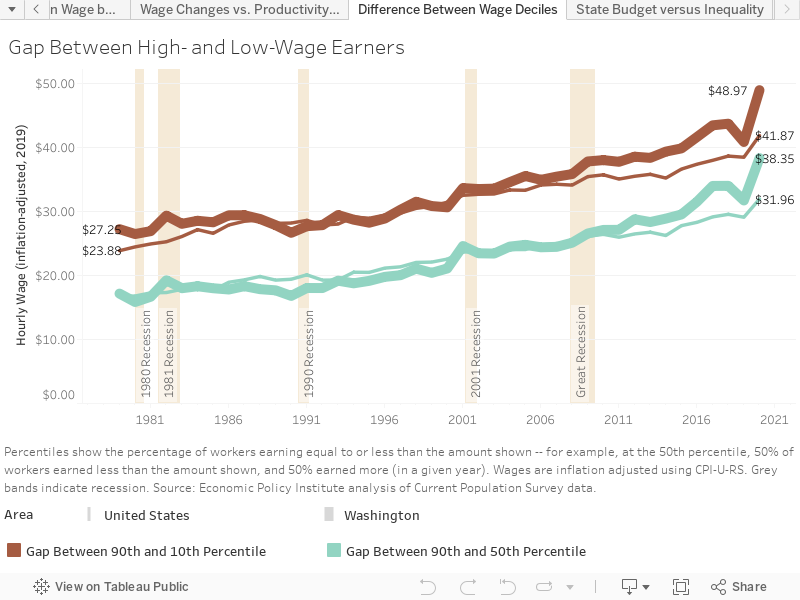

Wage inequality in Washington wasn’t always been so dramatic. Throughout the 1980’s, the relative difference in hourly wages between high- and low-wage workers was relatively stable – ranging from $25 to $27/hour (top 10 percent vs. lowest 10 percent), and $16 to $18/hour (top 10 percent vs. bottom 50 percent).

But during the 1990s, the wage gap between the top 10 percent and bottom 10 percent in Washington began to grow, eventually matching U.S. levels. By 2001, the gap between the top 10 percent and bottom 50 percent had done the same. The state’s top 10 percent/bottom 10 percent gap began growing faster than that of the U.S. in the years leading up to the Great Recession, and in the years afterward, so did the gap between the top 10 percent/bottom 50 percent.

As of 2019, the difference in hourly wages between high- and low-wage workers in Washington exceeds $31/hour (top 10 percent vs. bottom 50 percent) and $40/hour (top 10 percent vs. lowest 10 percent) – far outpacing the U.S. as a whole.

Income

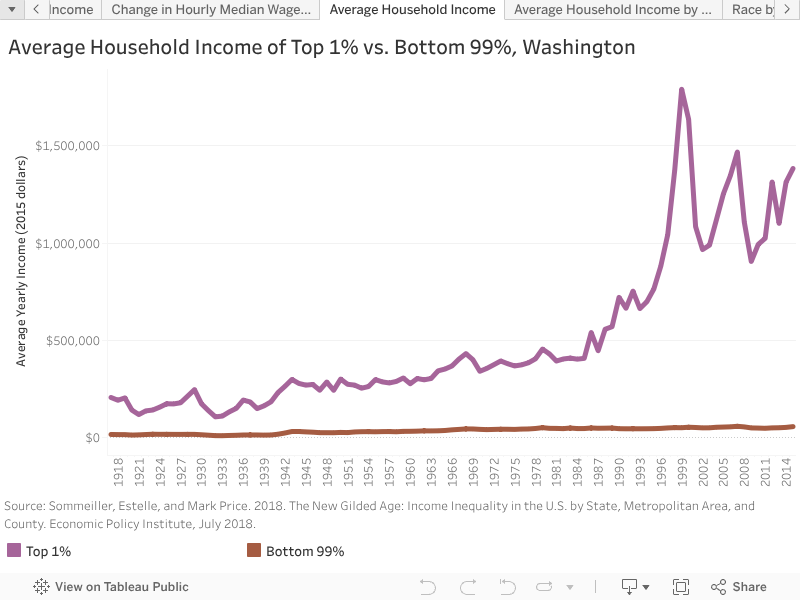

Hourly earnings are the most important source of total income for many households. But Social Security, pensions, investment income, and other sources also contribute. Investment income in particular contributes substantially to inequality growth. As of 2015, it takes a yearly income of $451,395 to be in the top 1% in Washington. The average income of the state’s top 1 percent ($1,383,223) was 24 times that of the bottom 99 percent ($57,100).

It hasn’t always been this way. Even during the so-called Roaring Twenties (late 1920’s) – during which the share of America’s wealth controlled by the richest of the rich increased rapidly – the top 1 percent brought in just 12 times the income of the bottom 99 percent. Post-WWII (from 1945 to 1973), Washington’s top 1 percent captured only 8.4 percent of overall income growth, such that as of 1973, incomes for the richest 1 percent of households were 9 times that of the other 99 percent. Since then, however, the top 1 percent has captured 43 percent of income growth, leaving far less for people further down the income ladder.[5]

Footnotes

[1] “Wages” include only hourly or salaried remuneration to employees.

[2] “Compensation” includes wage and salary disbursements, as well as supplements such as employer contributions for employee retirement plans, health coverage and social insurance. Note that to the extent that increased costs for health coverage represents only inflation, it is not an added benefit for employees, though it is included in measures of compensation.

[3] Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Real GDP by state, All industry total. Economic Policy Institute analysis of unpublished total economy data from Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Productivity and costs program; employment data from Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics; wage data from the Current Population Survey and compensation data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, State/National Income and Product Accounts public data series.

[4] Initiative 688 (approved by Washington voters in 1998) increased the minimum wage and required Washington state to make a yearly cost-of-living adjustment to the minimum wage starting in 2001. Initiative 1433 (approved by Washington voters in 2016) requires a statewide minimum wage of $11.00 in 2017, $11.50 in 2018, $12.00 in 2019, and $13.50 in 2020. Beginning in 2021, the minimum wage will receive a yearly cost-of-living adjustment.

[5] Sommeiller, Estelle, and Mark Price. 2018. The New Gilded Age: Income Inequality in the U.S. by State, Metropolitan Area, and County. Economic Policy Institute, July 2018.

More To Read

January 17, 2025

A look into the Department of Revenue’s Wealth Tax Study

A wealth tax can be reasonably and effectively implemented in Washington state

January 6, 2025

Initiative Measure 1 offers proven policies to fix Burien’s flawed minimum wage law

The city's current minimum wage ordinance gives with one hand while taking back with the other — but Initiative Measure 1 would fix that

September 24, 2024

Oregon and Washington: Different Tax Codes and Very Different Ballot Fights about Taxes this November

Structural differences in Oregon and Washington’s tax codes create the backdrop for very different conversations about taxes and fairness this fall